THOUGHT LEADERSHIP

ADAPT, OR DIE? SWIMMING AGAINST THE DEATH SPIRAL

Many countries are experiencing huge increases in distributed generation. Utilities are wondering whether it’s a blessing or a curse.

Electricity customers who have the funds and space to install distributed generation can reap direct benefits. Governments are variously over- or under-incentivising the growth of distributed generation, particularly solar PV on rooftops or in backyards.

There’s talk of death spirals and the weakening or undermining of the electricity supply establishment. Although I don’t buy all of the hype around the death spiral, it is real to an extent, and its implications present both opportunities and pitfalls.

Let’s look at the death spiral …

The ‘death spiral’ is the idea that as distributed generation and storage (such as solar PV and battery technologies) become cheaper, it becomes expedient for customers to disconnect from the electricity grid. As more customers leave, the sunk cost of the grid infrastructure must be borne by fewer customers. And so, it becomes expedient for a wider set of customers to disconnect, and so on until (potentially) no customers are connected and the asset owners are left with a huge white elephant.

This hypothesis of the death spiral is sound so long as the following assumptions hold:

- all customers can afford to leave the grid

- the electricity supply industry is a monolith that can’t adapt to changing market conditions.

Can all customers afford to leave the grid?

It’s hard to imagine that people living in high-density housing could get access to enough high-yield solar surface area to be able to be energy self-sufficient. This is especially true in less sunny climates with long periods of time in which proper access to sunshine cannot be guaranteed.

Additionally, can we imagine a time when the owners of rental properties install solar PV and batteries to attract tenants, especially at the low end of the rental market?

What about the high-volume users who supported or provided the impetus for the development of the centralised generation model in the first place? While they can choose to relocate to other regions for more competitive electricity tariffs, it is unlikely that they can go off-grid to any large extent.

Is the electricity industry really incapable of adapting?

Time will tell. This is complicated by government regulation and conflicts of interest or conflicting policies. Just as it is easy to accept that an economic imperative will drive off-gridding, isn’t the converse true? Off-gridding creates an economic imperative for the electricity supply industry to adapt. So that should convert the death spiral to some sort of controllable glide path for most.

What’s happening with load growth?

We can see that neither of the assumptions supporting the death spiral are as true as the doomsayers would have us believe.

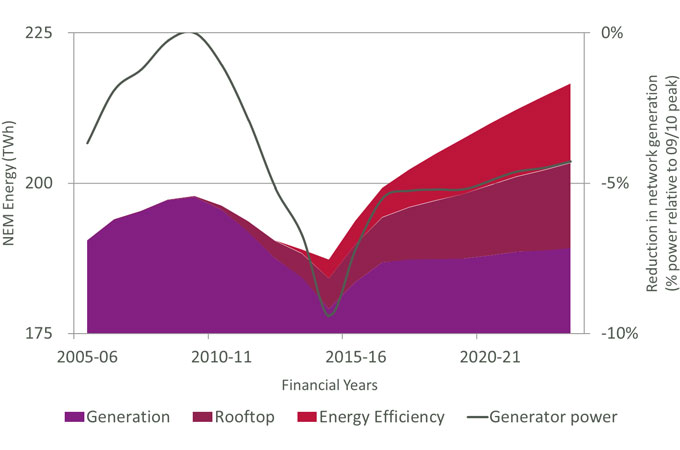

But there’s another issue we must consider: load growth. Australia is in a period of flat or negative load growth at the moment, perhaps due to the decline in manufacturing, the increased adoption of energy efficient appliances and other responses of consumers to price signals such as reducing use.

Manufacturing can only decline so far. Unless our demand for electricity can sustainably decline as well, energy efficiency can only decrease demand so much. If we imagine that our population will continue to grow, it is reasonable to assume that eventually demand will trend upwards again.

Can we imagine a future with no electricity grid?

We can and have removed the need for fixed-line telecommunications, but energy is a trickier beast.

While we still have large industrial power users remote from generation sources, and until all customers are able to generate and store according to their own requirements, some need for a power grid remains.

The grid of the future may not look like the one we have now. It may not be as reliable as the one we have now. The convenience and efficiency of sharing the cost for reliable reticulated power, however, is the one thing that the grid provides that distributed generation and storage may not.

What does this mean for the electricity industry now?

It means that we need to develop the ability to adapt.

This adaptation cannot be a purely defensive approach that tries to entrench the status quo. We must turn the challenges that confront us into opportunities to do business better.

Some concrete examples of successful adaptation could include:

- using distributed generation and storage to reduce network extension costs to new loads

- using our knowledge to inform regulators and governments of the implications of existing or proposed policies

- strategising about what enabling technologies could mean to our existing market offerings

- staying relevant by adopting and embedding these technologies to add value to our customers’ lives or businesses.

Adapting in practice

Specialist power and water consulting firm Entura has already demonstrated its innovative approach to some of these issues through the King Island Renewable Energy Integration Project and other small grid and off-grid projects. This work has given us practical experience of many developing technologies such as dynamic battery charging control, distributed or device-level demand-side management.

As part of Hydro Tasmania, Australia’s largest producer of renewable energy, we’ve also directly experienced how renewable generation can maximise benefits.

In my next article, I will explore the network benefits that may be realised from working with, rather than against, embedded and distributed generation. Subscribe to our newsletter to receive my next article.

If you would like to find out more about how Entura can help you swim against the death spiral and adapt successfully to the rapidly changing market for electricity generation and energy services, contact Donald Vaughan on +61 3 6245 4279.

About the author

Donald Vaughan is Entura’s Technical Director, Power. He has more than 25 years of experience providing advice on regulatory and technical requirements for generators, substations and transmission systems. Donald specialises in the performance of power systems. His experience with generating units, governors and excitation systems provides a helpful perspective on how the physical electrical network behaves and how it can support the transition to a high renewables environment.

MORE THOUGHT LEADERSHIP ARTICLES

21 April, 2015