THOUGHT LEADERSHIP

How the BESS general arrangement drives safety, certainty, speed and value

Despite the deceptively simple appearance of plug-and-play modularity, there’s a lot of crucial detail involved in achieving an efficient, safe and resilient BESS layout.

The layout or ‘general arrangement’ design will cover the BESS equipment (DC battery units/enclosures, PCS/inverters, medium-voltage transformers, switchgear, control and communications systems), the balance of plant (fire water tanks, buildings, laydowns, cable trenches, noise barriers, etc.) and the BESS substation.

Experience across the global BESS market shows that the devil is in the detail. In the push to accelerate renewable integration, there’s a danger that design decisions could be rushed, with too many details inadequately thought through or resolved. With a well-considered layout, a project is likely to move more quickly through approvals, construction and commissioning. A poorly designed project arrangement can embed inefficiencies, risks, delays and constraints that may be difficult to remedy.

Many developers have discovered that the layout of a BESS is a lever for risk, cost, speed and safety – with major implications for permitting, fire risk, insurability, environmental performance, lifecycle operating costs, augmentation and decommissioning complexity and, increasingly, community acceptance.

The BESS GA supports every phase of development

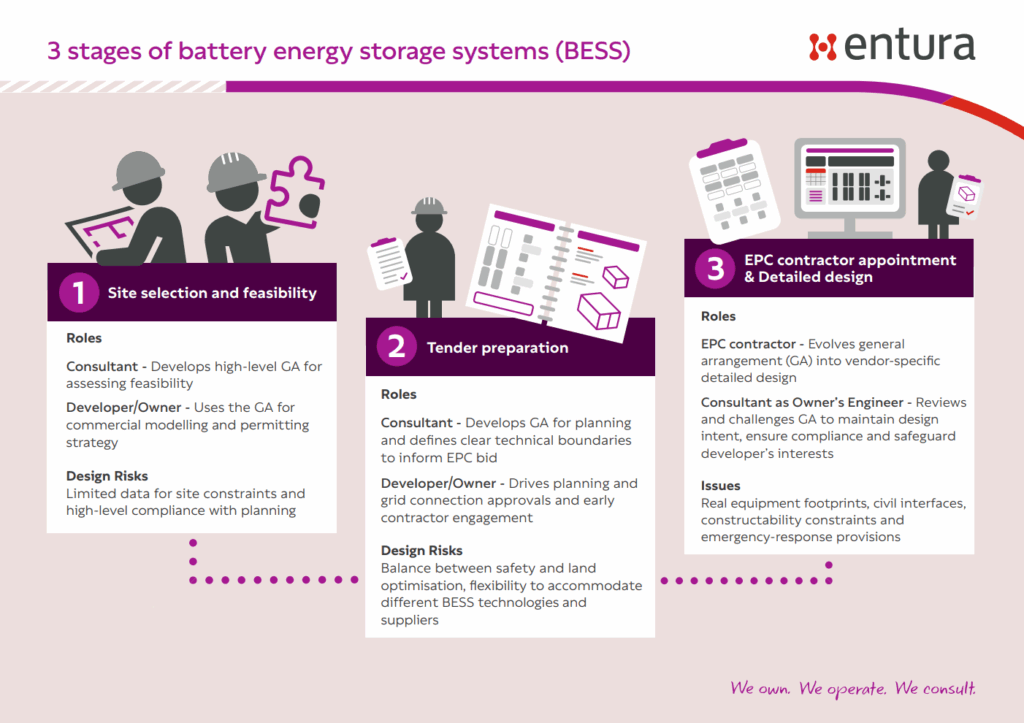

The responsibility for developing the BESS general arrangement (GA) shifts across the life of a project, and each iteration responds to the client’s evolving drivers, constraints and uncertainties. Early in development, the GA is typically prepared by the developer – or a consultant working under tight budgets – to support site selection, feasibility assessments and initial commercial decisions, often when project viability is not yet assured. As the project progresses into tender preparation, consultants refine the GA to define clear technical boundaries, ensuring EPC bids are accurate, comparable and compliant with planning requirements, fire safety and electrical standards.

Once an EPC contractor is appointed, the GA evolves into a vendor-specific detailed design, incorporating real equipment footprints, civil interfaces, constructability constraints and emergency-response provisions. The consultant – now acting as Owner’s Engineer – continues to review and challenge the GA to maintain design intent, ensure compliance and safeguard the developer’s interests throughout delivery.

Across all phases, a capable consultant adds value by anticipating the requirements of the utility and regulators, maintaining continuity through uncertainty, and designing with an appreciation of the developer’s realities – limited budgets, required studies, iterative decision cycles, and the constant question of whether the project will ultimately proceed – to ensure the final layout is safe, compliant and truly buildable.

Here we explore why GA decisions matter so much, and the key considerations shaping best-practice BESS arrangement today.

Navigating easements in BESS design

A workable GA begins with an accurate appreciation of the site’s constraints. Easements and land-use limits are not peripheral issues: they define the true buildable envelope and shape the BESS solution. Treat easements as primary design parameters rather than later checks.

Early identification and mapping of utility and service easements, gas pipelines, and other buried assets helps avoid design rework and ensures that access obligations and no-build zones are incorporated into the layout from day one, thereby reducing the risk of project delays. Hydrology deserves equal weight. Natural drainage paths and any stormwater easements identified through hydrological studies can restrict equipment placement, influence grading, and affect the location of roads and trenches. Flood mapping, too, should inform early decisions about elevating sensitive equipment or siting infrastructure on less exposed ground.

In many Australian settings, bushfire clearance requirements can dictate a reduced density and more generous separation between battery enclosures and vegetation. Where environmental or conservation easements exist, they may remove sizeable portions of land from consideration and require careful alignment with approval strategies.

Gather all easement, hydrology, flood and environmental information as early as possible, integrate it into spatial modelling, and shape the first iteration of the GA around these constraints. This will avoid the pitfall of attempting to impose an idealised arrangement on land that can’t support it and will create a stronger pathway to feasibility.

Addressing fire risk and emergency response

Given the nature of modern lithium battery technologies, fire risk must be front of mind. The spatial relationships between containers and the provision of firebreaks and passive barriers influence not only the likelihood of thermal events, but also whether a fire will spread beyond a single enclosure. Industry standards and guidelines as well as local fire codes provide structured approaches for managing separation distances, ventilation and fire-mitigation measures. The frameworks are increasingly referenced by regulators and insurers to verify that system layouts limit multi-unit fire spread.

Fire authorities in Australia now often expect evidence of large-scale fire testing which goes one step further by assuming the entire container is alight and evaluating whether the layout could allow fire to spread to adjacent units. Importantly, compliance is not limited to holding a certificate: the installed system must be constructed and configured in the same manner as the tested system, typically in accordance with the OEM’s certified design, internal spacing, materials and fire-mitigation features. Any deviation may invalidate the test assumptions and compromise fire-propagation performance.

Importantly, BESS technologies and safety standards continue to mature, with new insights regularly emerging from operational experience, incident investigations and evolving test methodologies. As a result, GAs must be developed with adaptability in mind, recognising that future updates to best practice or regulatory expectations may influence separation requirements, access provisions or fire-mitigation design.

Asset protection zones (APZs) are defined through a bushfire study. Requirements can vary even across a single site, reflecting changes in vegetation density or type, but recent projects have needed at least 10 m of separation on all sides.

The GA should support effective emergency response by providing clear access routes, equipment isolation points and adequate separation for firefighting operations – ensuring that the layout not only minimises the likelihood of fire spread but also enables authorities to intervene safely and efficiently. It’s crucial that the firefighting response is supported by engineered containment so that runoff remains within controlled zones. Grading, bunding and drainage design are therefore integral components of the overall GA, rather than secondary civil features.

Hybrid sites demand particular care, as the original renewable facility may not have been designed with BESS-specific hazards in mind. Shared roads, substations, cable routes and drainage systems must be adapted so that the BESS retains its own safety envelope.

Designing for construction, operation, maintenance and evolution

Construction is a real test for the GA. If adequate allowance isn’t made in the GA for heavy vehicle movements, crane access, delivery sequencing and temporary staging, projects are likely to run into significant costs and delays.

The size of the construction compound, laydown area and temporary storage will depend on the project scale, the number of trucks and size of workforce engaged, and the delivery and installation schedule. Critically, the expected size and reach of cranes, as well as the dimensions and handling requirements of major components such as transformers, need to be identified early in development so that access routes, turning circles, lifting zones and hardstand areas can be properly incorporated into the layout from the outset.

While a number of critical considerations should be defined during the concept design phase, it is inevitable that certain elements – such as final medium-voltage cable routing, auxiliary systems, drainage and other balance-of-plant details – will only be resolved as the design matures. To mitigate the risk of future spatial constraints leading to reduced capacity or alterations that could adversely affect the business case or grid-connection obligations, the initial GA should be intentionally developed with flexibility to accommodate later design requirements without compromising the ultimate capability of the facility.

Over the operational life of the BESS, the GA will continue to influence efficiency and cost. Reliable access for technicians, sufficient working clearances around major equipment and logical circulation routes are fundamental to safe and effective maintenance. Designs that overlook these requirements may appear economical on day one but can impose persistent operational inefficiencies over decades.

Energy storage assets built today must remain adaptable to tomorrow’s operating environment. As batteries degrade, room will be needed for augmentation or expansion – through reserved space, scalable electrical infrastructure and clear routing for future cabling. The increase in land area or civil cost is likely to be outweighed by the long-term benefit of being able to let the BESS evolve without major disruption.

No project is an island

BESS projects, like any other major infrastructure developments, will be subject to significant public scrutiny on issues such as fire risk, noise exposure, visual impacts, traffic movements and ecological impacts. Landowners, communities, stakeholders and regulators will want to know what impacts can be expected and how these will be managed. Many of these factors can be moderated to some extent by strategic placement and screening.

A clear and well-engineered GA needs to capture these considerations. It will demonstrate to regulators, stakeholders and the local community that project risks and impacts have been appropriately investigated, understood and managed – which will help build social and environment licence. A thoughtful GA is one of the most effective ways to build confidence in a project.

Make your GA a strategic advantage

As we’ve explored, the BESS GA is not just a technical document. It’s a set of strategic decisions where safety, social and environmental licence, operability, optionality and commercial performance intersect. Civil, electrical, mechanical, control, environmental and safety factors all influence – and are influenced by – the site arrangement, which makes it essential to bring an array of different perspectives and disciplines together early to avoid unforeseen flow-on implications and clashes among disciplines. At Entura, we integrate these streams to fully stress-test our designs and advice from all angles.

Now is the time to treat your BESS’s GA as one of the clearest opportunities to manage risk and materially improve your project outcomes.

To talk with us about your BESS project, contact Patrick Pease (Business Development Manager – Power & Renewables) or Donald Vaughan (Technical Director Power).

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Senior Renewable Energy and BESS Engineer Dr Rahmat Khezri has vast professional and technical experience with batteries. He has worked in the renewable energy and battery industry in project delivery from design, business case and feasibility analysis to operation and construction. Rahmat has managed several utility-scale BESS projects during his time with Entura, overseeing successful delivery while ensuring compliance with industry standards, optimising performance and managing key stakeholder relationships. Before joining Entura, he worked on projects supported by Sustainability Victoria for technical design and business case development of ‘second-life BESS’ using retired batteries of electric vehicles. In 2023–25, he was recognised by Stanford University as being in the top 2% of scientists worldwide for 3 consecutive years.

Dr Chris Blanksby is a Principal Engineer who uses his expertise in solar and battery technologies to provide strong leadership in delivering a range of services to the industry. Chris is Entura’s lead battery specialist and has been technical lead on several key projects in the Australian battery industry over the past years. Chris leads multidisciplinary teams in feasibility, design and construction supervision for utility-scale solar, battery, and hybrid integration projects. Projects Chris has led include Owner’s Engineer and independent engineer, feasibility studies, construction supervision, tariff reform and power purchase agreements, resource and energy yield analysis, project technical specification and principal’s project requirements, technical due diligence, model and control system development and network integration.

10 December, 2025