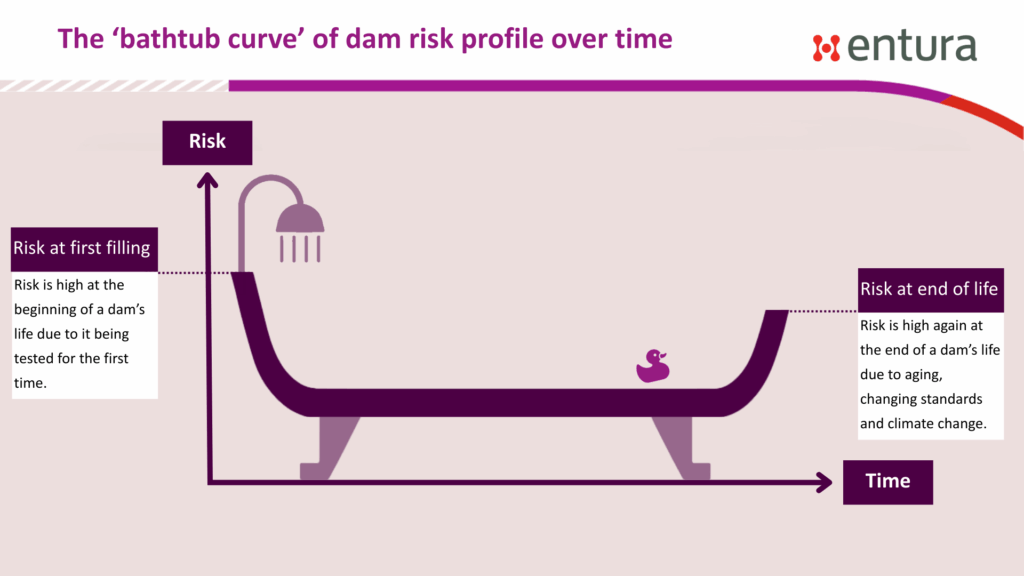

What do dams and bathtubs have in common?

The obvious answer is that both hold water, but there’s something more, which keynote speaker Andrew Watson of BC Hydro referred to at the recent NZSOLD/ANCOLD conference. He described the risk profile of a dam over time as ‘the bathtub curve’.

The riskiest periods for a dam are during the early years of operation and in later years as the dam starts to age.

We talk a lot about managing the risks of older dams through an appropriate dam safety program. A dam portfolio risk assessment is a great way of ensuring effort is focused appropriately. If the risk profile of an aging dam reaches an unacceptable level, this can result in a dam upgrade project. Clearly, there are many well-established processes and tools to manage risks on the aging dam side of the bathtub curve, but how about for new dams?

Reducing risk during design

During the design phase of a dam, we investigate the foundations, develop geological models to represent the foundation and assign geotechnical properties to the elements in our model. We also investigate materials that will be used in the dam, undertake laboratory testing to achieve material properties, and may even undertake insitu trials. We then model the dam structure to determine how it performs for various load cases, including extreme flood and earthquake loading, ensuring it meets the required engineering standards. Although the design process has checks and balances, some uncertainties and risks may have escaped identification at this stage.

Reducing risk during construction

The next phase is constructing the dam in accordance with the design specifications. A quality control assurance program sets quality control measures to give confidence that the construction meets the design requirements. Although the quality assurance and quality control systems are in place, there is still a level of uncertainty, making it difficult to guarantee that all the materials placed meet the required specification. Additionally, the foundation and material conditions may not totally reflect the design characterisation, necessitating modifications during construction. Typically, the designer is engaged in these changes, but was sufficient supervisory expertise on site to recognise these differences and engage the designer?

Reducing risk during first filling

For a dam design engineer, the filling of a new dam is often an exciting time. It is the completion of a major project, but it is also known to be the highest risk stage of a dam’s life. Everything that has gone into the design and construction of the dam is going to be tested for the first time: the design assumptions and models, the actual material properties, the engineering calculations, the quality of construction, the quality assurance systems, etc.

How can risk be mitigated during this first filling and the early years of operation, when the dam is being tested? From our experience, these practical steps can help reduce the risk (click each step for more details):

1) Ensure good technical governance through design and construction

2) Set up quality assurance and quality control systems

3) Continue a design presence on site

4) Use a risk framework to determine a dam’s readiness to impound

5) Have a dam safety system in place before impoundment

6) Maintain a heightened level of monitoring and surveillance

7) Be prepared in case of an unlikely dam safety emergency

8) Keep a close eye on the dam in its first years of operation and during new peaks

This process for new dams should apply equally to main dams and smaller saddle dams. In larger reservoirs, water may not fill against a saddle dam for a year or two after the commencement of impoundment. In this case, the same principles should be applied to the saddle dam during the period when water is against it for the first time. These principles also apply when a dam is raised, because when water load is placed against the raised section, the raised dam is being tested for the first time.

By applying these steps through the heightened risk period during first filling and the first 5 years of operation, dam professionals can mitigate the risks associated with the early side of the bathtub curve, helping the dam get a good start in life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Herweynen is Entura’s Technical Director, Water. He has more than 3 decades of experience in dam and hydropower engineering, working throughout the Indo-Pacific region on both dam and hydropower projects. His experience covers all aspects including investigations, feasibility studies, detailed design, construction liaison, operation and maintenance, and risk assessment for both new and existing projects. Richard has been part of a number of expert review panels for major water projects. He participated in the ANCOLD working group for concrete gravity dams and was the Chairman of the ICOLD technical committee on engineering activities in the planning process for water resources projects. Richard has won many engineering excellence and innovation awards (including Engineers Australia’s Professional Engineer of the Year 2012 – Tasmanian Division), and has published more than 30 technical papers on dam engineering.

Poutès Dam – a model of sustainable dam redevelopment

Having been named as the Planning Institute of Australia’s Young Planner of the Year for 2023 and awarded a bursary, Entura’s Bunfu Yu travelled through Switzerland and France to study hydropower and energy innovation. Her tour to Poutès Dam in France made a powerful impression. Here she reflects on what Poutès Dam demonstrates about environmentally driven engineering design and how genuine engagement with stakeholders in a design process can lead to balanced outcomes …

The Poutès Dam, located on the upper Allier River, a tributary of the Loire River in central France, has become a landmark case study of how to reconcile renewable energy production with environmental restoration. It’s a project that benefitted from genuine engagement, environmental-led engineering design principles, and future-conscious leadership by its operator, Electricité de France (EDF).

The dam was built during World War II without the usual approval processes. It has long been an obstacle to migratory fish, such as Atlantic salmon from the Allier basin, blocking the return of spawners and the downstream migration of juveniles. It has also disrupted the natural sediment flow of the Allier.

From conflict to collaboration

In the 1980s, environmental organisations highlighted the impact of the dam as a cause of the drastic decline in the wild Atlantic salmon population in the Loire-Allier basin. A sustained mobilisation of environmental groups through the 1990s evolved into a lengthy anti-dam campaign. In the mid-2000s, when EDF applied to renew its operating concession, it attracted criticism and rejection from global environmental NGOs, including WWF.

After decades of debate involving local communities, environmental NGOs, the dam operator (EDF Hydro) and public authorities, a compromise was reached in the late 2000s by which the parties agreed on a commitment to sustainable hydropower. Rather than completely remove the dam, a large-scale reconfiguration project – dubbed the ‘New Poutès’ – was born.

In 2015, EDF achieved a 50-year renewal of its licence, conditional on stringent environmental performance requirements, particularly regarding fish migration and sediment transport. It marked a new life for the project: those who once stood on the site of the dam in protest were now collaboratively discussing the future of Poutès with the operator and public authorities.

The ‘New Poutès’ project

A substantial refurbishment of the dam was carried out over several years to 2021, with the renovated dam inaugurated in October 2022. The design carefully configured to improve salmon migration and achieve the desired environmental outcomes.

- The dam height was lowered from 18 m to 7 m to reduce the water head and the reservoir’s impact. The embankment is also shaped in such a way that, along with the reduced hydraulic drop, the fish have a shorter and smoother vertical barrier to overcome.

- The reservoir length was decreased from 3.5 km to under 500 m, restoring much of the river’s natural profile (including a natural river gradient that allows salmon to swim) and rebuilding downstream spawning habitat.

- Two large centrally located sluice gates were installed, which can be fully opened during fish migration seasons and for high-flow water releases, allowing sediments and aquatic fauna to circulate freely. This is considered the key innovation to rejuvenate the river’s ecological dynamics.

- Fish-pass structures (fishway and fish elevator) have been incorporated in the design, which operate every 2 minutes to ensure upstream and downstream migration is effective.

- While the turbine flow remains similar to before, generation is paused during key periods to prioritise fauna movement.

The fish ladder in action

Ecological and social benefits match technical success

The New Poutès redevelopment did more than update an old hydropower plant; it reconnected a fractured ecosystem, restoring sediment flow and providing effective fish migration routes. The New Poutès continues to supply about 85% of its original hydroelectric output.

Importantly, this project demonstrates the potential of ‘collective intelligence’; that is, collaboration among diverse stakeholders (government, operator, NGOs, local communities) to produce outcomes that are superior to those achieved through conflict or unilateral decisions.

Moreover, it challenges the notion that dams are immutable – a rigid infrastructure at odds with the environment. Instead, New Poutès embodies a modern, adaptive approach: engineering solutions that evolve over time, responding to environmental and social imperatives.

Lessons from Poutès

As many dam owners and operators consider the future of their aging dams and the need for sustainable management, New Poutès stands out as a model. It shows that:

- with thoughtful design and management, hydropower and biodiversity can coexist

- partial removal and targeted retrofitting of a dam can sometimes be a cost-effective and ecologically positive alternative to full demolition

- restored rivers can recover ecological functions like fish migration, sediment transport and dynamic flow regimes, contributing to broader goals of ecological resilience

- multi-stakeholder participatory processes combining NGOs, operators, authorities and communities can help reconcile competing interests and produce durable solutions.

For me, as a planning specialist, this last point resonated particularly powerfully. It’s exciting to see a project that has learned from the lessons of the past, engaged openly and genuinely with its community, and navigated a path toward greater long-term sustainability.

When environmental, social and heritage values are considered from the outset and integrated into dam design, upgrades and refurbishments, the outcomes are better for everyone. In the Poutès story, it took the loss of the operating licence to make a major leap. Proactive efforts to bring a better balance to the ledger of impacts verse benefits may help avoid such dramatic circumstances.

Having finished my study trip and returned to Tasmania, I’m excited to continue my involvement in Entura’s projects involving dam refurbishment, redevelopment and upgrades – including the new lease on life being planned for Hydro Tasmania’s Tarraleah hydropower station. This project is sure to find itself amongst global examples of leading practice, setting the standard for other owners of older hydropower assets.

Bunfu thanks EDF team members Benoit Houdant (Technical Director Engineering) and Sylvain Lecuna (project manager of the Poutes Dam project), and Roberto Epple (former President of the European Rivers Network) for the site tour. It was incredible to share a site tour with representatives of 2 parties that were once in opposition, but now share in the pride of Poutès.

Poutès Dam and surrounding topography

Close-up of Poutès Dam

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bunfu Yu is a dynamic young leader in renewable energy planning, approvals and business development. Bunfu was named the National Young Planner of the Year by the Planning Institute of Australia. This honour recognised not only her passion for planning and delivering renewable infrastructure but also her active contribution to the profession through mentoring, public engagement and knowledge sharing. She is currently a Senior Environmental Planner and a Business Development Manager at Entura.

How the BESS general arrangement drives safety, certainty, speed and value

Despite the deceptively simple appearance of plug-and-play modularity, there’s a lot of crucial detail involved in achieving an efficient, safe and resilient BESS layout.

The layout or ‘general arrangement’ design will cover the BESS equipment (DC battery units/enclosures, PCS/inverters, medium-voltage transformers, switchgear, control and communications systems), the balance of plant (fire water tanks, buildings, laydowns, cable trenches, noise barriers, etc.) and the BESS substation.

Experience across the global BESS market shows that the devil is in the detail. In the push to accelerate renewable integration, there’s a danger that design decisions could be rushed, with too many details inadequately thought through or resolved. With a well-considered layout, a project is likely to move more quickly through approvals, construction and commissioning. A poorly designed project arrangement can embed inefficiencies, risks, delays and constraints that may be difficult to remedy.

Many developers have discovered that the layout of a BESS is a lever for risk, cost, speed and safety – with major implications for permitting, fire risk, insurability, environmental performance, lifecycle operating costs, augmentation and decommissioning complexity and, increasingly, community acceptance.

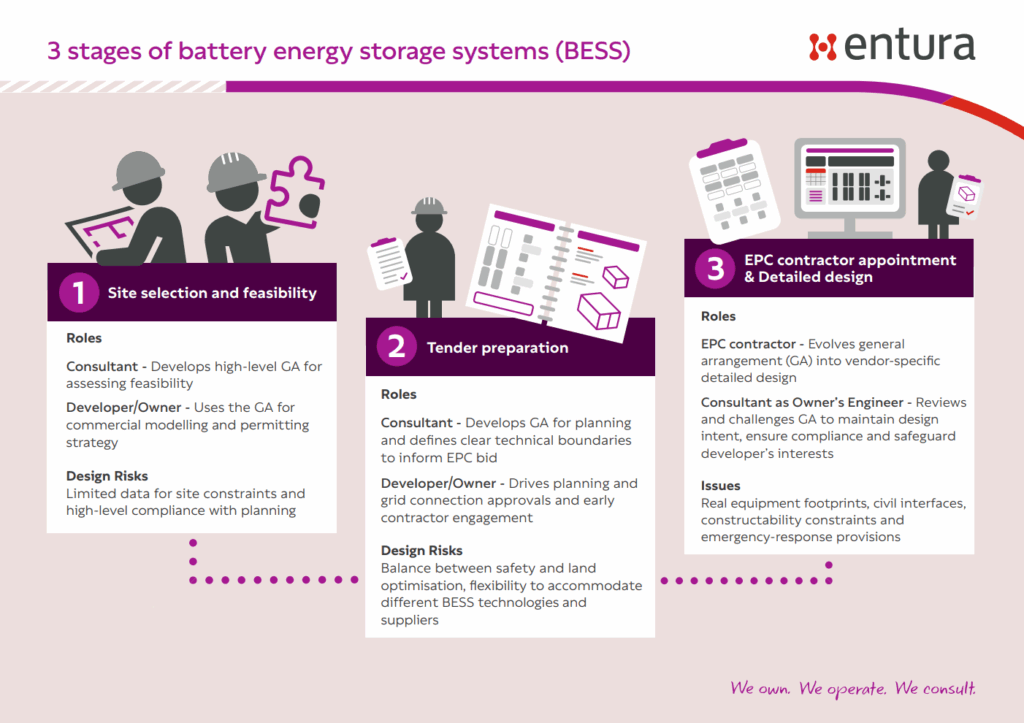

The BESS GA supports every phase of development

The responsibility for developing the BESS general arrangement (GA) shifts across the life of a project, and each iteration responds to the client’s evolving drivers, constraints and uncertainties. Early in development, the GA is typically prepared by the developer – or a consultant working under tight budgets – to support site selection, feasibility assessments and initial commercial decisions, often when project viability is not yet assured. As the project progresses into tender preparation, consultants refine the GA to define clear technical boundaries, ensuring EPC bids are accurate, comparable and compliant with planning requirements, fire safety and electrical standards.

Once an EPC contractor is appointed, the GA evolves into a vendor-specific detailed design, incorporating real equipment footprints, civil interfaces, constructability constraints and emergency-response provisions. The consultant – now acting as Owner’s Engineer – continues to review and challenge the GA to maintain design intent, ensure compliance and safeguard the developer’s interests throughout delivery.

Across all phases, a capable consultant adds value by anticipating the requirements of the utility and regulators, maintaining continuity through uncertainty, and designing with an appreciation of the developer’s realities – limited budgets, required studies, iterative decision cycles, and the constant question of whether the project will ultimately proceed – to ensure the final layout is safe, compliant and truly buildable.

Here we explore why GA decisions matter so much, and the key considerations shaping best-practice BESS arrangement today.

Navigating easements in BESS design

A workable GA begins with an accurate appreciation of the site’s constraints. Easements and land-use limits are not peripheral issues: they define the true buildable envelope and shape the BESS solution. Treat easements as primary design parameters rather than later checks.

Early identification and mapping of utility and service easements, gas pipelines, and other buried assets helps avoid design rework and ensures that access obligations and no-build zones are incorporated into the layout from day one, thereby reducing the risk of project delays. Hydrology deserves equal weight. Natural drainage paths and any stormwater easements identified through hydrological studies can restrict equipment placement, influence grading, and affect the location of roads and trenches. Flood mapping, too, should inform early decisions about elevating sensitive equipment or siting infrastructure on less exposed ground.

In many Australian settings, bushfire clearance requirements can dictate a reduced density and more generous separation between battery enclosures and vegetation. Where environmental or conservation easements exist, they may remove sizeable portions of land from consideration and require careful alignment with approval strategies.

Gather all easement, hydrology, flood and environmental information as early as possible, integrate it into spatial modelling, and shape the first iteration of the GA around these constraints. This will avoid the pitfall of attempting to impose an idealised arrangement on land that can’t support it and will create a stronger pathway to feasibility.

Addressing fire risk and emergency response

Given the nature of modern lithium battery technologies, fire risk must be front of mind. The spatial relationships between containers and the provision of firebreaks and passive barriers influence not only the likelihood of thermal events, but also whether a fire will spread beyond a single enclosure. Industry standards and guidelines as well as local fire codes provide structured approaches for managing separation distances, ventilation and fire-mitigation measures. The frameworks are increasingly referenced by regulators and insurers to verify that system layouts limit multi-unit fire spread.

Fire authorities in Australia now often expect evidence of large-scale fire testing which goes one step further by assuming the entire container is alight and evaluating whether the layout could allow fire to spread to adjacent units. Importantly, compliance is not limited to holding a certificate: the installed system must be constructed and configured in the same manner as the tested system, typically in accordance with the OEM’s certified design, internal spacing, materials and fire-mitigation features. Any deviation may invalidate the test assumptions and compromise fire-propagation performance.

Importantly, BESS technologies and safety standards continue to mature, with new insights regularly emerging from operational experience, incident investigations and evolving test methodologies. As a result, GAs must be developed with adaptability in mind, recognising that future updates to best practice or regulatory expectations may influence separation requirements, access provisions or fire-mitigation design.

Asset protection zones (APZs) are defined through a bushfire study. Requirements can vary even across a single site, reflecting changes in vegetation density or type, but recent projects have needed at least 10 m of separation on all sides.

The GA should support effective emergency response by providing clear access routes, equipment isolation points and adequate separation for firefighting operations – ensuring that the layout not only minimises the likelihood of fire spread but also enables authorities to intervene safely and efficiently. It’s crucial that the firefighting response is supported by engineered containment so that runoff remains within controlled zones. Grading, bunding and drainage design are therefore integral components of the overall GA, rather than secondary civil features.

Hybrid sites demand particular care, as the original renewable facility may not have been designed with BESS-specific hazards in mind. Shared roads, substations, cable routes and drainage systems must be adapted so that the BESS retains its own safety envelope.

Designing for construction, operation, maintenance and evolution

Construction is a real test for the GA. If adequate allowance isn’t made in the GA for heavy vehicle movements, crane access, delivery sequencing and temporary staging, projects are likely to run into significant costs and delays.

The size of the construction compound, laydown area and temporary storage will depend on the project scale, the number of trucks and size of workforce engaged, and the delivery and installation schedule. Critically, the expected size and reach of cranes, as well as the dimensions and handling requirements of major components such as transformers, need to be identified early in development so that access routes, turning circles, lifting zones and hardstand areas can be properly incorporated into the layout from the outset.

While a number of critical considerations should be defined during the concept design phase, it is inevitable that certain elements – such as final medium-voltage cable routing, auxiliary systems, drainage and other balance-of-plant details – will only be resolved as the design matures. To mitigate the risk of future spatial constraints leading to reduced capacity or alterations that could adversely affect the business case or grid-connection obligations, the initial GA should be intentionally developed with flexibility to accommodate later design requirements without compromising the ultimate capability of the facility.

Over the operational life of the BESS, the GA will continue to influence efficiency and cost. Reliable access for technicians, sufficient working clearances around major equipment and logical circulation routes are fundamental to safe and effective maintenance. Designs that overlook these requirements may appear economical on day one but can impose persistent operational inefficiencies over decades.

Energy storage assets built today must remain adaptable to tomorrow’s operating environment. As batteries degrade, room will be needed for augmentation or expansion – through reserved space, scalable electrical infrastructure and clear routing for future cabling. The increase in land area or civil cost is likely to be outweighed by the long-term benefit of being able to let the BESS evolve without major disruption.

No project is an island

BESS projects, like any other major infrastructure developments, will be subject to significant public scrutiny on issues such as fire risk, noise exposure, visual impacts, traffic movements and ecological impacts. Landowners, communities, stakeholders and regulators will want to know what impacts can be expected and how these will be managed. Many of these factors can be moderated to some extent by strategic placement and screening.

A clear and well-engineered GA needs to capture these considerations. It will demonstrate to regulators, stakeholders and the local community that project risks and impacts have been appropriately investigated, understood and managed – which will help build social and environment licence. A thoughtful GA is one of the most effective ways to build confidence in a project.

Make your GA a strategic advantage

As we’ve explored, the BESS GA is not just a technical document. It’s a set of strategic decisions where safety, social and environmental licence, operability, optionality and commercial performance intersect. Civil, electrical, mechanical, control, environmental and safety factors all influence – and are influenced by – the site arrangement, which makes it essential to bring an array of different perspectives and disciplines together early to avoid unforeseen flow-on implications and clashes among disciplines. At Entura, we integrate these streams to fully stress-test our designs and advice from all angles.

Now is the time to treat your BESS’s GA as one of the clearest opportunities to manage risk and materially improve your project outcomes.

To talk with us about your BESS project, contact Patrick Pease (Business Development Manager – Power & Renewables) or Donald Vaughan (Technical Director Power).

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Senior Renewable Energy and BESS Engineer Dr Rahmat Khezri has vast professional and technical experience with batteries. He has worked in the renewable energy and battery industry in project delivery from design, business case and feasibility analysis to operation and construction. Rahmat has managed several utility-scale BESS projects during his time with Entura, overseeing successful delivery while ensuring compliance with industry standards, optimising performance and managing key stakeholder relationships. Before joining Entura, he worked on projects supported by Sustainability Victoria for technical design and business case development of ‘second-life BESS’ using retired batteries of electric vehicles. In 2023–25, he was recognised by Stanford University as being in the top 2% of scientists worldwide for 3 consecutive years.

Dr Chris Blanksby is a Principal Engineer who uses his expertise in solar and battery technologies to provide strong leadership in delivering a range of services to the industry. Chris is Entura’s lead battery specialist and has been technical lead on several key projects in the Australian battery industry over the past years. Chris leads multidisciplinary teams in feasibility, design and construction supervision for utility-scale solar, battery, and hybrid integration projects. Projects Chris has led include Owner’s Engineer and independent engineer, feasibility studies, construction supervision, tariff reform and power purchase agreements, resource and energy yield analysis, project technical specification and principal’s project requirements, technical due diligence, model and control system development and network integration.

Dam decommissioning: old dams, new opportunities

While many dams have very long lives, and could in theory operate for centuries, some dams reach a point at which decommissioning becomes a realistic final phase of the dam life cycle.

Decommissioning is not something that happens very often, given the significant value of dams and their functions, which are often multiple. Maintaining and upgrading dams, rather than decommissioning, can sometimes also be a more sustainable solution if this extracts more economic, social and environmental value to offset the initial impacts that the dam may have caused when originally constructed.

However, decommissioning may be the best option if the dam is no longer needed to deliver its original purpose, if it is no longer providing commercial or societal benefits, or if it is considered too costly to continue maintaining the dam or to undertake the necessary upgrades to stay compliant with contemporary regulations and standards.

How is a decision to decommission made?

The decision to decommission a dam is usually based on a comprehensive risk assessment. Risk assessments play a critical role in managing dams throughout their life cycle. They primarily focus on ensuring safety and minimising risks associated with dam operation, failure and decommissioning.

Risk assessments estimate risks, identify hazards and failure modes, evaluate the tolerability of the risk, compare potential risk reduction measures if needed, and establish a risk reduction strategy.

If the risk is not tolerable, risk reduction measures will be recommended, and a risk reduction strategy will be established to reduce the risk. The risk reduction measures will generally involve upgrade works. When the option to undertake dam upgrade works is considered, the option to decommission the dam is often also included. The dam owner can then undertake a cost–benefit analysis to determine the most viable option, understand the level of risk reduction achieved, and consider less tangible aspects such as community concerns.

What’s involved in decommissioning a dam?

Decommissioning a dam requires considerable planning to minimise environmental impacts and reduce the chance of leaving any residual hazards in the long term. A thorough assessment of the site conditions and downstream environment is a crucial first step towards identifying the appropriate decommissioning actions.

The location of the dam and the details of the dam works will determine the planning requirements, which often include:

- engineering design – taking breach width and batters into account to remove the possibility of retaining water, and assessing the impact on flooding downstream (as dams frequently provide flood mitigation even when this is not their primary function)

- sediment and erosion control planning – as sediment release can cause significant water quality issues and harm to habitats downstream. It is important to note that the reservoir area will initially be unvegetated and will not have any topsoil that can be used to support vegetation growth to control erosion. Additionally, sediments will typically have been deposited in the dam reservoir and are generally very easily remobilised, so this needs special attention from the designers

- flora, fauna and cultural heritage studies – as decommissioning can dramatically alter ecosystems both upstream and downstream, and heritage features can often be highlighted improving the amenity of the new asset. Ecological studies such as flora and fauna assessments are important to identify any threatened species that need to be considered in the decommissioning plans, such as through exclusion zones or timing the works to minimise impacts (e.g. conducting work outside of breeding seasons)

- fluvial geomorphology assessment – which identifies how rivers interact with their landscapes and how they change over time. It is important to understand this given that the decommissioned dam will have water flowing through it rather than retaining water, changing the balance of erosion and sedimentation processes

- dam safety emergency plan for decommissioning works – to protect communities from flooding during the decommissioning works

- regulatory approvals – a dam decommissioning permit will be needed, which will include managing any specific regulatory requirements such as issuing a notice of intent prior to commencing works and providing work-as-executed reports and drawings at the completion of the works to confirm all conditions have been successfully met.

- Depending on the use and location of the dam, it is recommended to consult with a range of stakeholders, including the local community and council, during the planning process to ensure that their perspectives and concerns are considered early. If the dam is located near to residences, public spaces or other civic amenities, extensive consultation is likely to be needed due to the potential nuisance from the works (e.g. noise, dust and additional traffic in the local area). A masterplan can be developed through this process of consultation, outlining potential options for remediating and repurposing the area based on the community’s priorities, such as creating potential new community assets such as wetlands, parks or sporting facilities.

The work involved in decommissioning a dam will depend on the type of dam and the surrounding environment but commonly involves:

- re-routing inflow away from the reservoir or past the dam

- removing all or part of the dam wall

- modifying or removing the outlet works

- lowering the spillway crest level or removing the spillway control gates or stop-boards

- treating retained liquid prior to discharging it in a safe condition

- stockpiling and stabilising accumulated sediments from within the reservoir

- removing or encapsulating impounded material, such as trees and vegetation

- revegetating the reservoir area and rehabilitating the site to perform its new purpose.

Doing it safely

Decommissioning a dam is a very complex matter involving many stakeholders and often taking some time to reach its conclusion, so it is prudent for dam owners to embark early on some interim measures to rapidly reduce any identified dam safety risks. The simplest and most cost-effective risk reduction measure is usually to lower the level of the reservoir.

The next stage is identifying the planning requirements and works involved with decommissioning and developing a decommissioning plan. The engineering design, included in the decommissioning plan, will consider the necessary environmental assessments and ensure adherence to appropriate guidelines.

Common considerations when developing the engineering design include:

- hydrological and hydraulic assessment of conditions before and after decommissioning

- the necessary breach width and batters to make the site safe

- safely discharging or removing retained water and material

- the volume of any attenuated water remaining after decommissioning

- gradient of the land if the reservoir is being completely drained

- erosion and sediment control during and after decommissioning

- managing inflows and floods during the decommissioning

- careful consideration of the final land use after decommissioning including the ecological restoration and community uses.

Achieving success

For decommissioning to be considered successful, it’s crucial that the decommissioning plan and engineering design take account of the priorities that emerge from stakeholder consultation. Many communities become attached to a dam as part of their local landscape, especially if the dam is very old. They may wish for some of the dam’s heritage to be retained or acknowledged in some way, such as retaining and integrating parts of the abutment into the future form or land use where it is safe to do so, or echoing the past by incorporating smaller water features into the resulting site.

Another major consideration for successful decommissioning is controlling erosion and sediment. Reservoirs typically have a low point that can function as a temporary sediment basin once the water level is substantially lowered. Rainfall and inflows can be channelled with small bunds and hessian silt rolls to the sediment basin. Turbid water can then settle or be treated, if necessary, before being pumped out. After decommissioning, erosion and sediment can be managed by revegetating exposed areas with native plants, creating habitat features such as wetlands or log jams, and managing and monitoring wildlife to ensure their adaptation to the changing environment. Simple solutions can be implemented to achieve positive – or at least neutral – outcomes for biodiversity.

Right process, right people

Decommissioning dams takes a wide range of skills to deliver a successful outcome – from hydrology and hydraulics, environmental and heritage assessments, through to detailed construction planning and a vision for the repurposed land. With the right people and process, decommissioning can reduce safety risks to the community, protect the environment during the works, and ultimately create new, sustainable assets enhancing the amenity of the area for the benefit of communities now and long into the future.

Entura has been involved in a number of dam decommissioning projects including Waratah Dam and Tolosa Dam. To talk with Entura’s specialists about a dam decommissioning project, contact Richard Herweynen or Phillip Ellerton.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joey Scicluna is a civil engineer, who began his career managing commercial and subdivision projects. Since joining Entura’s dams and geotechnical team in 2022, he has undertaken a wide range of dam safety surveillance inspections and reporting, dam safety modelling and analysis and risk assessments. Joey has been the lead author for a number of intermediate and comprehensive dam safety reviews, and has developed design concepts and conducted feasibility studies for existing and new dams projects. Joey enjoys problem solving and working with stakeholders to achieve the best outcome for every project.

Risk is the word – reflections on the NZSOLD/ANCOLD 2025 conference

From 19 to 21 November 2025, industry experts from consultants to asset owners gathered in Ōtautahi Christchurch, New Zealand, to exchange insights, challenge thinking and strengthen connections ‘across the ditch’ and beyond. Here Entura’s Sammy Gibbs reflects on the conference …

If I had dollar for every time I heard the word ‘risk’ across the two-day event, I might have been able to fund next year’s conference myself!

Why was this the case? As noted in many of the presentations and papers, the dam industry is facing the combined challenges of aging dam infrastructure, changing design standards, climate change impacts, community expectations and resource/cost constraints. As a result, the industry is shifting more towards risk-informed decision-making/frameworks, compared to traditional standards-based approaches,to manage and design dam infrastructure.

No dam is 100% safe and all risks can never be designed out entirely, but a sophisticated understanding of their risk can inform our decisions and actions so that we can target key issues cost-effectively and ensure resilience in our dams and water infrastructure.

Risks in asset ownership

In his opening address, Andrew Watson, Director of Dam Safety & Generation Asset Planning at BC Hydro in Canada, provided valuable insights into how BC Hydro uses a risk-informed framework to manage its dams. He discussed the use of a ‘vulnerability index’ to understand the significance of identified physical deficiencies in the dam portfolio. The higher the index, the greater the likelihood that the deficiency would result in poor performance. This index allows BC Hydro’s dam safety team to understand the overall risk profile and prioritise future works. It left us contemplating how the ANCOLD 2022 Risk Assessment Guidelines and ALARP process may be enhanced by integrating components of this approach. This could be a useful way of measuring how far the dam is from meeting ‘best practice’ and hence enhance the justification for further risk reduction or accepting the position as ALARP.

Later in the conference, Andrew Watson was joined by Peter Mulvihill, Lelio Mejia and Barton Maher to discuss legacy risk and how to manage it. Legacy risk is relevant for many asset owners (nationally and internationally) as our sector faces the complexities of inheriting aging facilities, acquired from past organisations/owners. A key challenge with these legacy structures is the transfer of knowledge to new asset owners. Important records such as monitoring data, design and construction information are often lost (or were never developed), making it difficult to understand and quantify the current risk position of the structure. These aging facilities are also unlikely to meet current design standards or withstand climate change impacts. Risk-informed decision making and phased approaches become critical in such instances, as does asking the question ‘Does it matter?’ when it comes to unknowns. Like tying surveillance programs to key failure modes, unknowns should also be associated with credible failure modes.

It was noted that for some of these structures the most appropriate solution is decommissioning, as the risk imposed by the structure (and the cost to mitigate it) may outweigh the economic benefit of the asset itself. In such instances, this decision can provide social and environmental benefits and are worth investigating.

Risk in surveillance monitoring

The conference reaffirmed the critical role of risk-based surveillance monitoring and the importance of understanding how dam instrumentation relates to key failure modes and/or performance. The most effective tool to support this is an event decision tree.

Entura’s Diego Real reiterated the importance of understanding key failure modes when implementing instrumentation upgrades. His paper presented a staged approach for the upgrades, providing clients with a cost-effective, practical solution that assists in managing dam safety risks.

Although there was discussion about various ways in which surveillance programs can be optimised, our industry is aligned in recognising the criticality of undertaking routine inspections as the first line of defence when it comes to identifying potential failure indicators.

Risk mitigation solutions

Several presenters shared examples of bespoke solutions responding to dam risks – including Entura’s Jaretha Lombaard, who highlighted how a Swedish berm was used to mitigate risks associated with piping failures at an earth and rockfill embankment dam in Tasmania.

Other risk mitigation solutions presented included non-physical works such as improvements in surveillance and monitoring. In one example, alarm systems in rivers are being used effectively to warn and evacuate the public in a swimming pool downstream in the event of a flood. Instead of relying solely on costly capital-intensive physical upgrades, the most effective strategy for reducing societal risks may lie in enhancing the speed and reliability of early warning systems.

Sharing knowledge to tackle similar problems

NZSOLD/ANCOLD 2025 was an excellent opportunity to see how specialists are tackling the complex challenges facing the dams industry. Walking away, my mind was full of phrases involving the word ‘risk’, but I felt reassured that we are all facing similar problems and by sharing our knowledge and innovations we’re continually improving our ability to design, monitor and maintain dams.

This conference will be a tough act to follow, but I look forward to the 2026 ANCOLD conference to be held in Lutruwita/ Tasmania (where I live and Entura originated).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sammy Gibbs is a civil engineer with 7 years of consulting experience and joined Entura’s Dams and Geotech Team in May 2021. Sammy has a diverse background in dam and water engineering and works on a range of projects including consequence category assessments, hydrology studies, hydraulic design, risk assessments and dam design projects.

Reflections from MYCOLD 2025: Innovation, resilient dams and the evolving role of hydropower

Earlier this month, I had the privilege of joining colleagues from across Malaysia and the region at the 3rd International Conference on Dam Safety Management and Engineering (ICDSME2025), organised by the Malaysia Commission on Large Dams (MYCOLD), held in Kuching, Sarawak. There’s a particular energy that comes with a MYCOLD conference – part reunion, part technical deep-dive, part regional conversation about water, resilience and community safety.

I returned energised and inspired – not only by the technical excellence on display, but also by the sense of shared purpose across our industry and the tangible people-to-people exchanges and collaborations. With energy systems transforming rapidly, climate change accelerating and dam safety expectations strengthening, it has never been more important for dam and hydropower professionals to share openly and learn from one another. ICDSME2025 offered that in abundance.

Here are just a few reflections on some of what I heard …

Reimagining hydropower in changing markets and climates

In the ‘Advancing sustainable hydropower’ session, I shared perspectives from Tasmania’s long hydropower journey and Entura’s experience supporting the state’s major renewable energy initiatives.

My message was clear: the feasibility of pumped hydro or of reimagining conventional hydropower isn’t simply a technical question of ‘can we build it?’ but ‘what is the long-term value it creates?’ Smart choices depend on a holistic understanding of context – i.e. the markets, energy mix, climate, environmental impacts and benefits, and community perspectives and impacts. Pumped hydro is never ‘impact-free’, and it is not inherently more sustainable than conventional hydropower. What matters is how we think about the future of the energy transition, understanding what role pumped hydro can play in that context, how well we select sites, how carefully we consider environmental and social impacts, and how thoughtfully we design (and extend) assets for long-term economic and social value.

With wind and solar dominating new energy investment in Australia, hydropower’s baseload role can shift to respond to evolving market dynamics. Hydropower’s deep storage, flexibility and system stability are becoming increasingly important. We’re seeing these opportunities in Tasmania, where both conventional hydropower and pumped hydro could – with more interconnection to the mainland – help balance a renewables-rich National Electricity Market while returning extra revenue to Tasmania and increasing the reliability of supply across Australia’s south-east.

Climate change adds further complexity to feasibility considerations. Changing rainfall patterns, more variable inflows and more frequent extremes – as well as with the increasingly variable generation mix and how energy sources interact – all influence when hydropower can generate or store.

Ultimately, I believe there are not only opportunities with extending operating life, refurbishing or redeveloping dam assets; there are also obligations upon us as an industry to do our best for the sustainability of these assets. We need to focus constantly on how to optimise outcomes from the base impacts of hydropower or dam developments and seek ways to reduce impacts into the future. We also need to think about how to deliver great outcomes and value that extends across a long asset life, beyond the limited commercial timeframes considered in final investment decisions.

Technology, people and the future of dam safety

I had the honour of chairing a keynote session featuring Yang Berbahagia Prof. Datin Ir. Dr. Lariyah binti Mohd Sidek and Dr Martin Wieland.

Dr Wieland’s insights into the seismic performance of dams reminded us that strong engineering fundamentals remain as crucial as ever, even as digital tools advance. Prof. Lariyah explored how digital platforms, artificial intelligence and risk-based frameworks are shaping the next generation of dam safety practice. She emphasised the importance of the human layer: building institutional readiness, strengthening safety culture, fostering stakeholder trust, and ensuring effective engagement with communities.

Together, their perspectives reinforced that the future of dam safety will depend on both technological innovation and human-centred capability and how effectively these dimensions interact. That’s something Entura is focused on as we continue to bring deep expertise and experience, while exploring and testing the possibilities of new technology to support design and analysis.

Learning from incidents to strengthen global knowledge

Another highlight for me was chairing a session on dam surveillance, monitoring and evaluation. Seven presentations, while different in context and purpose, in combination emphasised the power of data and the importance of learning from experience.

A standout paper examined the 2022 landslide incident at Kenyir Dam, an event that occurred quite soon after Entura’s dam safety inspector training program used the dam as a site visit capstone. Despite extreme rainfall and slope instability, and some damage to appurtenant structures and spillway, instrumentation data confirmed that the dam behaved as designed. What was also clear was that, largely, the instrumentation in place and the data that was able to be collected was a positive demonstration of the importance of robust dam design and monitoring systems.

Another paper explored machine-learning approaches to forecasting short-term reservoir levels at Batang Ai Hydroelectric Project – a scheme with which Entura has long been associated. The results were impressive and point to a future where AI-supported forecasting strengthens real-time operations, especially under increasing climate variability.

These are exactly the kinds of insights our industry must continue to share openly and widely. We can never ‘design out’ all risk, but we can reduce it through good data and continual reflection and learning from real-world events.

Strengthening long-term capability in Malaysia

ICDSME2025 also highlighted the importance of building capability – something I am passionate about. It was encouraging to see Malaysia’s Certified Dam Safety Inspector program, developed with input from Entura’s training arm ECEWI, growing into a sustained and locally led pathway, launched during the conference. Strengthening dam safety ultimately depends on skilled people and strong institutions, making investment in training an investment in long-term sustainability of dam safety governance – and ultimately greater national resilience. We hope to continue to work with MYCOLD to determine how our specialised expertise can further enhance capability uplift beyond surveillance, extending to dam safety risk decision making and dam safety engineering.

A shared commitment to the future

Conferences like ICDSME2025 are timely reminders of our collective responsibility and the shared purpose we need to bring to the challenges ahead. We’re all navigating the same landscape, and when we come together – sharing data, stories and lessons – we accelerate progress for everyone.

I am grateful to MYCOLD for the invitation to contribute and for the generous knowledge-sharing throughout the event. I left Sarawak optimistic: the connection, commitment and collaboration across our sector have never been stronger as we work toward our common goal: safer, more sustainable dams and hydropower systems that support resilient futures.

Can you trust advanced tools without qualified professionals behind them?

To make confident decisions about renewable energy assets – from building a wind farm to monitoring dam performance or optimising asset management – owners and operators need precision data they can trust.

As the renewable energy sector becomes increasingly digitised, the quality of measurements matters more than ever. Digital twins, predictive analytics, AI-driven performance tools and remote operations all depend on reliable, precise and traceable data.

Good data provides visibility. It lets owners and operators detect faults or safety issues early, optimise performance, and protect reliability and revenue. For example, accurate turbine alignment during installation or refurbishment could save hundreds of thousands of dollars in downtime and maintenance.

However, data only provides value if it has the right level of accuracy for the job intended. If the data isn’t up to scratch, the decisions won’t be either.

Keeping pace with technology is a steep learning curve

Surveying has always been the backbone of infrastructure development, land management and industrial precision. From the early days of using theodolites and chains to today’s cutting-edge technologies like laser scanning, UAV photogrammetry and LiDAR, the discipline has evolved dramatically. Yet, one constant remains: the need for appropriately qualified and experienced professionals.

Surveying is far more than measuring distances – and achieving precision requires more than sophisticated instruments. It requires a deep understanding of geodesy, data integrity, error propagation and spatial analysis. Traditional instruments such as theodolites and total stations demand mastery of angular measurement and trigonometric principles. GNSS-based methods introduce complexities like satellite geometry, atmospheric corrections and datum transformations. As technology advances, the learning curve steepens: laser scanners and UAVs generate massive point clouds, while LiDAR systems demand expertise in filtering, classification and 3D modelling.

Surveying principles now extend beyond land and construction into industrial metrology, where precision is measured in microns rather than millimetres. In the renewable energy sector, the applications are vast, from assessing hydropower turbine blade wear and integrity of concrete structures to verifying the verticality of wind turbines and ensuring accurate positioning of new hydraulic equipment. Here, advanced techniques like laser trackers and terrestrial laser scanning dominate, and the margin for error is extremely small.

Precision gives confidence that the data feeding an asset’s digital models is accurate, consistent and aligned with recognised standards. When survey instruments, operational sensors and digital monitoring systems all work within a strong metrological framework, asset owners can be confident that their decisions are based on fact, not noise.

The human behind the technology

However sophisticated today’s measurement tools and technologies may be, their outputs are only as trustworthy as the professionals behind them.

Without properly qualified and experienced operators, advanced tools can become liabilities rather than assets. Misinterpretation of data or incorrect calibration can lead to costly errors in construction, infrastructure alignment or asset management.

Using the wrong technique or sensor for the use case and conditions, neglecting appropriate calibration, and a lack of adequate redundancy can lead to major issues and costly mistakes.

Specialised, qualified professionals will think through these issues early, ensuring that accuracy and tolerance requirements are clearly defined from the start and that data integrity is maintained throughout with robust quality control and assurance procedures.

Human insight provides the environmental and engineering context and assurance that automated systems alone cannot deliver. Surveying and metrology professionals can determine whether readings are valid and offsets are accounted for – and will be able to distinguish genuine change from measurement anomalies.

Ultimately, it is professional judgement that transforms accurate data into actionable insights and confident decisions.

Accuracy drives advantage

Today’s surveying advances are transforming how decisions are made. Spatial data is no longer just a technical input; when validated and interpreted by qualified professionals, it becomes a valuable source of real strategic insight and advantage. When the data is right from the start, every subsequent step becomes more certain and the outcomes have the best chance of being more efficient and sustainable. Such clarity can be the difference between success throughout an asset’s lifecycle and expensive lessons learned.

As technologies advance, so does the need for qualified professionals who understand both the science of measurement and the realities of complex, dynamic infrastructure. By ensuring accuracy, compliance with standards and efficient workflows, the qualified surveyor safeguards projects from financial and reputational risks – enabling the reliability, safety and commercial confidence that every asset owner depends on.

If you’d like to talk to us about the potential of advanced surveying and metrology on your project, contact Phillip Ellerton or a member of our Spatial & Data Services Team.

Unlocking repowering for Australia’s older wind farms

Europe and the US are already upgrading older wind farms with powerful new turbines. Repowering could potentially offer significant opportunities in Australia’s energy transition, but there are barriers. Australia risks falling behind unless action is taken now to make repowering easier, faster and more attractive for investors. Dr Andrew Wright, Bunfu Yu and Donald Vaughan explore the opportunities for intervention …

To accelerate the clean energy transition, repowering old wind farms should be a serious consideration. Many of Australia’s earliest wind farms are reaching the middle or end of their design lives. These projects were pioneering at the time, but today’s turbines are taller, more efficient and capable of generating far more electricity from the same site – which is likely to have some of Australia’s strongest and most consistent wind.

Repowering could potentially offer a faster, cheaper and less disruptive way to boost renewable generation than building entirely new projects. Yet, despite the clear potential, repowering is still rare in Australia.

The pending closure of Pacific Blue’s Codrington Wind Farm in Victoria announced in February 2025 is an interesting case study, demonstrating potential barriers. Pacific Blue has concluded that a project with new wind turbines at Codrington is not financially viable once the existing turbines reach the end of their useful life. Consisting of 14 x 1.3 MW wind turbines and completed in June 2001, Codrington is one of the earliest wind farms completed in Australia. The site no doubt has a great wind resource, but its small size and the limited capacity of the 66 kV grid connection do not suit modern wind turbines, which are typically at least 4 times the size and capacity.

Codrington is the largest old wind farm to announce its decommissioning in Australia. But other large early projects of similar age are also facing decisions about repowering or decommissioning.

This raises a question: are government and regulatory authorities properly prepared for an influx of ‘new old’ projects?

There is an expectation that larger wind farms will repower with new wind turbines, using and perhaps augmenting existing grid connections, under new development permits. But this concept is yet to be tested and proven in Australia.

How should governments and regulatory authorities in Australia deal with the planning approval aspects of repowering wind farms? Presently, they are considered like any other new development – but other countries have shown that repowering can be unlocked with practical mechanisms to incentivise developers, streamline planning and ease grid connection hurdles.

Incentivising repowering

Repowering requires significant capital investment – so a targeted financial incentive could make a meaningful difference in getting the project to stack up.

In Europe, there is a growing view that governments are not doing enough to drive forward the repowering of older wind farms that might otherwise carry on operating with inefficient use of land and resources. Local communities are typically comfortable living in the vicinity of wind farms that have been operating for a long period, so there is a strong argument that governments should develop specific policies to encourage repowering of old sites that already have community acceptance.

Germany led the way in direct policy intervention with a ‘repowering bonus’ included in 2009 in its Renewable Energy Sources Act, rewarding wind farm owners with a EUR 0.5 cent/kWh feed-in tariff bonus for replacing older wind turbines with modern, higher-capacity machines. This policy delivered more energy from fewer turbines while reducing land-use impacts. Repowering has subsequently become a significant contributor to Germany’s wind energy growth, with 1.1 GW of new wind capacity in 2023 coming from repowering.

In the USA, the Production Tax Credit (PTC) is now phasing out. This is an example of a policy that encouraged repowering as an unintended consequence. Enacted in 1992, it provided businesses with a tax credit per MWh of electricity generation for the first 10 years of a wind farm’s life. This created an incentive to generate as much output as possible for 10 years, and then build a new project to renew the tax credit. Given that 10 years is too short a lifetime for a well-engineered and well-run wind farm, this is not an ideal example of incentivising repowering.

Australia has no equivalent incentive for repowering. Early wind farms like Challicum Hills in Victoria, Starfish Hill in South Australia, and Tasmania’s Woolnorth wind farms are now approaching the end of their operating lives. Direct financial incentives or market mechanisms rewarding greater efficiency, reliability and grid services provided by repowered assets could make the difference between decommissioning these assets or repowering with new wind turbines to deliver decades more renewable energy.

Navigating approvals

In most cases, repowering will require additional planning and environmental approvals. This depends on the scale of the changes: are the turbines taller? are there new civil works? is the layout shifting? what new accesses or grid connection corridors might be required? The success of repowering depends on navigating approvals with the same care and thoroughness as for new projects.

Policy positions and guidelines have evolved over the last 2 decades, and there are now more stringent guidelines dictating the matters for consideration during approvals. Additional threatened or endangered species may also have been listed over the years.

Community engagement is a critical part of repowering and should not be overlooked. Even where communities have co-existed with a wind farm for decades, taller turbines or different layouts could raise new concerns about landscape impacts or amenity. Early dialogue and transparent benefit-sharing will help build trust and engagement in the project.

Clear planning, targeted environmental studies, and early engagement with regulators and communities can help projects capture the benefits of modern technology while minimising risks of delay.

A dedicated fast-track pathway for repowering would help these projects progress. Such a pathway could recognise prior approvals, with updates only where impacts materially change (e.g. taller turbine heights, new technology, and the cumulative effects of other developments), or where environmental values have changed. This doesn’t mean bypassing safeguards or consultation, but it does mean matching the level of scrutiny to the level of risk.

Easing grid connection challenges

Connecting a repowered project to the grid inevitably involves meeting stricter requirements than the original project, which will take time and add cost. Yet there is a strong argument that repowered projects should have some special considerations, given the differences between a greenfield development plugging into an existing network, and a replacement of an existing project with newer technology.

Proponents are faced with three paths: a new connection to the current rules, a grandfathered connection under the previous rules, or a hybrid approach. All of these have benefits and drawbacks. The best path will depend on the like-for-likeness of the repowering in terms of size, turbine technology and the amount of reused equipment (transformers and other electrical balance of plant).

Another consideration is whether the non-scheduled status of early wind farms can be preserved through this process. It is likely that significant changes to power or energy output may trigger a change. As a minimum, model accuracy requirements will apply to a new connection – which may lead to more detailed testing than the plant had previously been subjected to.

Options to help alleviate these challenges could include tailored connection pathways that recognise existing infrastructure, de-coupling from grid queue management for repowering projects, and clear technical standards so developers know what to expect.

As well as accelerating repowering, this could help make better use of grid assets, reducing pressure for new transmission.

What now for repowering?

Jurisdictions in Europe and the USA demonstrate that repowering works when governments set the right conditions. Early Australian projects such as Codrington, Starfish Hill, Challicum Hills and Woolnorth wind farms show that the time to decide is already here.

Given the challenges to achieve timely and cost-effective repowering in Australia, should we leave the low-hanging fruit of legacy sites dormant for now, and keep deploying capital on scale-efficient large sites in the short term?

Prioritising efficient large sites makes sense for urgent growth, but there are ways to pursue both greenfield and repowering – and the advantages of repowering remain. The early wind farms were built in some of the windiest, most accessible locations in Australia. Leaving these sites dormant would waste high-quality wind assets where there may already be community goodwill and existing grid assets.

Now is the time to consider whether particular site design approaches could make a site more easily repowerable in future – such as the way reticulation is installed, different approaches to foundations, scalable switchrooms and yard layouts. Is there a niche for wind turbine OEMs to offer lower power variants of new designs to better suit the scale of repower sites? Creativity and innovation will be needed – because the transition is too big and too urgent for us to leave repowering in the ‘too hard’ basket.

By pursuing both new developments and repowering simultaneously, Australia could capture immediate growth from large-scale projects while also making efficient use of our best wind resources and existing assets, maintaining community benefits and regional employment, and avoiding a wave of retired or stranded capacity.

If you are considering your wind farm’s future options and opportunities, please contact Andrew Wright or Patrick Pease.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr Andrew Wright is Entura’s Senior Principal, Renewables and Energy Storage. He has more than 20 years of experience in the renewable energy sector spanning resource assessment, site identification, equipment selection (wind and solar), development of technical documentation and contractual agreements, operational assessments and Owner’s/Lender’s Engineer services. Andrew has worked closely with Entura’s key clients and wind farm operators on operational projects, including analysing wind turbine performance data to identify reasons for wind farm underperformance and for estimates of long-term energy output. He has an in-depth understanding of the energy industry in Australia, while his international consulting experience includes New Zealand, China, India, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, the Philippines and Micronesia.

Bunfu Yu is a dynamic young leader in renewable energy planning, approvals, and business development. Bunfu played a pivotal role in Entura’s Environment and Planning Team’s success in achieving the Planning Institute of Australia’s National Award for Stakeholder Engagement in 2024. In 2023, Bunfu was named the National Young Planner of the Year by the Planning Institute of Australia. This honour recognised not only her passion for the planning and delivery of renewable infrastructure but also her active contribution to the profession through mentoring, public engagement, and knowledge sharing. She is currently a Senior Environmental Planner and a Business Development Manager at Entura.

Donald Vaughan has over 20 years’ experience providing advice on regulatory and technical requirements for generators, substations and transmission systems. He has worked for all areas of the electrical industry, including generators, equipment suppliers, customers, NSPs and market operators. Donald specialises in the performance of power systems. His experience in generating units, governors and excitation systems provides a helpful perspective on how the physical electrical network behaves.

From feasibility to operations: how technical due diligence can empower renewable energy investment

Confident investment in renewable energy projects is the key to accelerating the clean energy transition. Yet every renewable energy project carries some uncertainties at every stage, from early feasibility to long-term operations.

For all involved – developers and contractors, investors and lenders, stakeholders and communities – trust in a project’s viability and success will grow when there is a strong framework in place to thoroughly assess and quantify the project’s technical and financial assumptions, risks and unknowns.

Robust technical due diligence needs to span all the stages of the project’s development, though its focus will change as the project evolves.

Here we examine how sound technical due diligence, applied throughout the lifecycle of a renewable energy project, can provide a strong foundation for sustainable delivery and greater confidence of a bankable investment.

Due diligence is an ongoing process

Technical due diligence of renewable energy projects (including wind, solar or hydropower) isn’t a one-off activity. It evolves as a project advances.

The aim in the early stage is to verify the design assumptions and to determine if a concept can evolve into a viable investment.

During execution (construction), the emphasis shifts to project monitoring and adaptive risk management, ensuring that construction progress aligns with budgeted milestones.

Once operational, the focus is on assessing the project’s outputs (energy generation, efficiency, etc.) and maintenance practices while also ensuring contractual integrity, which is critical for refinancing or acquisition decisions.

Together, these different phases of due diligence form a continuum of technical supervision which ultimately helps to support the long-term success of the project.

Pre-construction phase

Pre-construction due diligence is a multidisciplinary process that assesses site conditions, verifies design feasibility, and validates operational feasibility. This leads to more realistic financial projections, which in turn enable objective and systematic investment decisions.

Key elements of pre-construction due diligence typically include review or assessment of the following:

– environmental approval status and consent conditions

– geological and geotechnical studies

– hydrology and hydraulic components (hydropower)

– mechanical and electrical equipment

– power evacuation and grid connection

– constructability and logistics

– unit rates and project costs

– pre-construction risk assessment

Execution phase (construction)

Once a project secures financing and enters the construction phase, the technical due diligence focus moves to active oversight of whether the project is being delivered safely, efficiently and to the required standard. The consultant helps the project achieve timely outcomes during construction and commissioning. The key elements of technical supervision during construction include the following:

– ongoing design reviews

– initial review of the execution plan

– construction quality monitoring

– construction progress monitoring

– updated risk assessments

– assurance of adherence to standards

– identification of opportunities for continuous improvement

– milestone reporting

These assessments help to identify deviations from plans, enhance transparency and reinforce investor confidence.

Operational phase (existing assets)

For businesses considering investing in or acquiring operational assets, due diligence helps to assess how the asset is performing, verify the asset’s physical condition, and identify improvements that can sustain value into the future. This is essential for establishing accurate valuations and identifying hidden risks. A competent technical consultant can offer tailored services that combine desktop reviews with on-site inspections to inform the investment decision.

Key components of due diligence of existing assets include the following:

– review of condition of plant and equipment

– performance review

– review of O&M

– hydrological assessment (hydropower)

– risk identification

This stage of due diligence is especially relevant in a secondary market, where investors are seeking to invest in brownfield assets to diversify their portfolios. The goal is to ensure that the asset’s operational reality matches its financial promise.

Building confidence from concept to operation

Entura has seen firsthand how due diligence strengthens projects at every stage. We’ve fulfilled many technical due diligence and advisory roles in different contexts – and sometimes multiple roles on a single project.

For continuity, a single consultancy can take on a range of responsibilities across the different phases of a project: whether that’s technical feasibility assessment, technical due diligence, Owner’s or Lender’s Engineer roles, or Independent Technical Advisor. These roles are different in focus, timing and perspective, but they’re ultimately all about building confidence in the viability and success of the project.

One example is the Kidston Pumped Storage Project (K2-Hydro), for which Entura initially prepared the technical feasibility assessment considering factors that influence the project’s technical and commercial viability, and then played an advisory role leading to financial close. During the construction phase, our role shifted to that of Owner’s Engineer, helping to ensure the project’s designs meet current practice and that construction is implemented in accordance with the designs and specifications.

In the pre-construction stage, Entura has completed technical due diligence of many hydropower and other renewable energy projects. For example, we’ve recently taken on this role for several hydropower projects planned for development in India, ranging from a 32 MW hydropower project right through to an 1800 MW pumped storage project. These assessments included hydrological studies, power potential studies and reviews of project layout, plant design and electro-mechanical works, power evacuation arrangements, power purchase agreements, technical risks, costs and construction schedule, and more.

We’ve also conducted due diligence for many solar, wind and hybrid renewable energy projects. For example, Entura was engaged as the technical due diligence consultant for the 112 MW Granville Harbour Wind Farm to support the client’s financial closure. We provided technical services including energy estimates, review of permits and grid connection, development of technical specifications, review of the project design, and checks of environmental compliance– all necessary for successful financial closure.

We continued our involvement into the construction stage as Owner’s Engineer, providing construction support, overseeing the civil and geotechnical components of construction, and conducting regular site inspections to ensure the works were undertaken in accordance with the relevant industry and safety standards.

Translating technical findings into financial indicators

Technical due diligence at every stage of a project’s lifecycle requires a level of rigour that goes beyond a simple compliance requirement. It is fundamental to long-term asset performance, stakeholder trust and the validity of financial assumptions and projections. Consultants involved through the feasibility, construction and operational phases can contribute meaningfully to the project development.

Although financial modelling lies outside a technical consultant’s scope, their work forms the backbone for credible financial analysis and investment decisions that are integral to the overall business case development. Each finding from the technical process can be used to support further financial due diligence to inform investment, lending or acquisition decisions.

By structuring the technical findings around the following four financial pillars, technical due diligence becomes a bridge between the on-the-ground realities of the project and its ultimate financial viability.

Capital and operational expenditure

Energy production and revenue estimates

Financing arrangements

Financial appraisal parameters

What does this mean for stakeholders?

Sound technical due diligence can cater to the financial expectations of different stakeholders making it a key instrument for strategic decision support.

- Long-term investors (developers or buyers) prioritise clarity on returns, dividend sustainability, and resilience of the asset into the future. Their confidence hinges on realistic operation plans, reliable energy forecasts, and durable O&M strategies derived from feasibility assessments and construction-phase monitoring.

- Debt providers focus on debt-service coverage ratios (DSCR) which indicate the capacity of the project to generate sufficient revenue to repay loans. Lenders will want reassurance about budget contingencies, capability of contractors and robustness of project schedules – all of which are assessed in detail during the due diligence.

- Insurers require information about structural failure modes, the risks of operational outage, and force-majeure conditions. These can be informed by detailed technical analyses and condition assessments from operational audits.

When applied consistently throughout the course of a project, from feasibility to operations, technical due diligence helps all stakeholders measure project risks, avoid unexpected costs, and evaluate potential and actual performance. This is the bedrock for confident financial decisions – and ultimately, for driving the energy transition forward at the scale and pace our environment and communities urgently need.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sagar Shiwakoti is a civil engineer with master’s degree in water resources engineering and close to a decade of experience in flood studies (hydrological and hydraulic assessment) and hydraulic design for hydropower projects. Prior to joining Entura in 2022, he worked with the Nepal Electricity Authority and Hydroelectricity Investment and Development Company, where he gained extensive experience in technical due diligence for hydropower projects. Sagar was also a lecturer in civil engineering for a number of years at Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu.

New technologies give deeper insight to protect the shallows

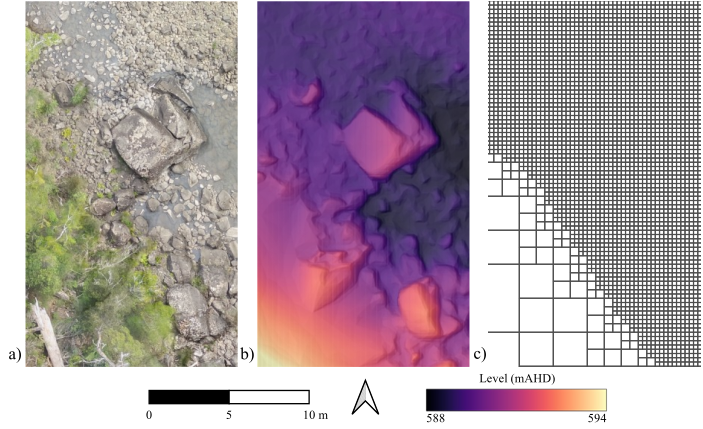

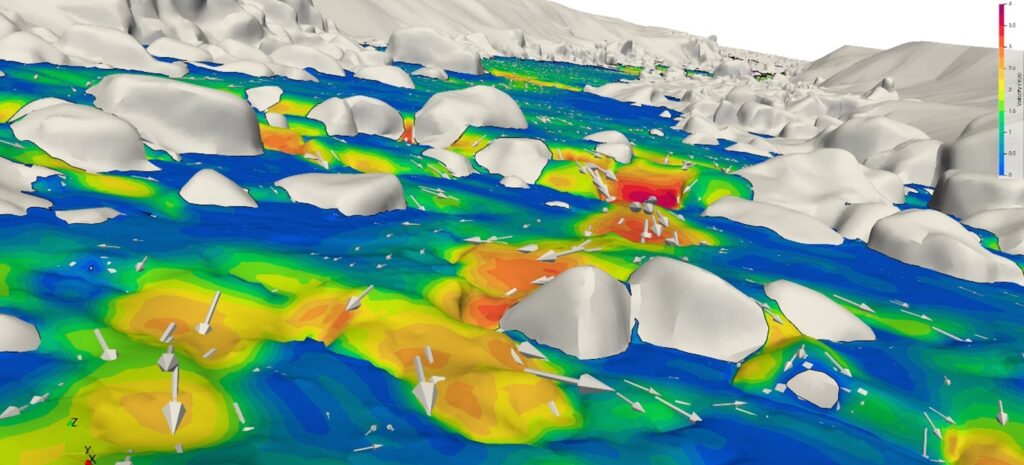

Water is a precious resource for communities and industries – and for the health of river ecosystems. Balancing these needs around dams can be very complex. In this article, Dr Will Elvey and Dr Colin Terry explore how advanced technologies and methods can help dam owners/operators better understand shallow downstream areas to support aquatic biodiversity …

Dams are crucial for many communities, providing water security, energy and economic growth – but they also change the natural flow of rivers and streams.