Dam decommissioning: old dams, new opportunities

While many dams have very long lives, and could in theory operate for centuries, some dams reach a point at which decommissioning becomes a realistic final phase of the dam life cycle.

Decommissioning is not something that happens very often, given the significant value of dams and their functions, which are often multiple. Maintaining and upgrading dams, rather than decommissioning, can sometimes also be a more sustainable solution if this extracts more economic, social and environmental value to offset the initial impacts that the dam may have caused when originally constructed.

However, decommissioning may be the best option if the dam is no longer needed to deliver its original purpose, if it is no longer providing commercial or societal benefits, or if it is considered too costly to continue maintaining the dam or to undertake the necessary upgrades to stay compliant with contemporary regulations and standards.

How is a decision to decommission made?

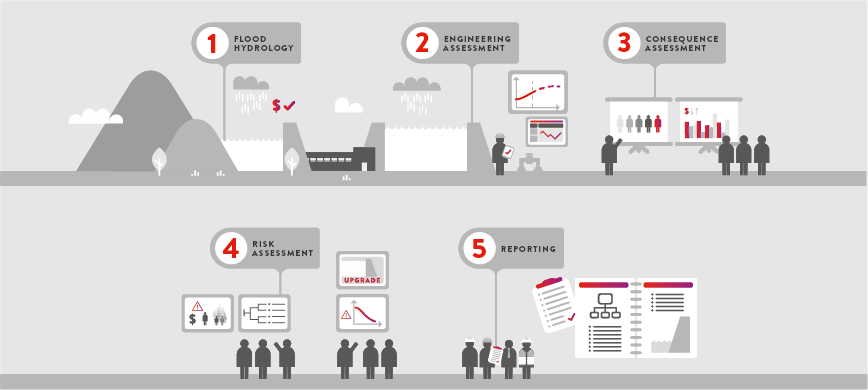

The decision to decommission a dam is usually based on a comprehensive risk assessment. Risk assessments play a critical role in managing dams throughout their life cycle. They primarily focus on ensuring safety and minimising risks associated with dam operation, failure and decommissioning.

Risk assessments estimate risks, identify hazards and failure modes, evaluate the tolerability of the risk, compare potential risk reduction measures if needed, and establish a risk reduction strategy.

If the risk is not tolerable, risk reduction measures will be recommended, and a risk reduction strategy will be established to reduce the risk. The risk reduction measures will generally involve upgrade works. When the option to undertake dam upgrade works is considered, the option to decommission the dam is often also included. The dam owner can then undertake a cost–benefit analysis to determine the most viable option, understand the level of risk reduction achieved, and consider less tangible aspects such as community concerns.

What’s involved in decommissioning a dam?

Decommissioning a dam requires considerable planning to minimise environmental impacts and reduce the chance of leaving any residual hazards in the long term. A thorough assessment of the site conditions and downstream environment is a crucial first step towards identifying the appropriate decommissioning actions.

The location of the dam and the details of the dam works will determine the planning requirements, which often include:

- engineering design – taking breach width and batters into account to remove the possibility of retaining water, and assessing the impact on flooding downstream (as dams frequently provide flood mitigation even when this is not their primary function)

- sediment and erosion control planning – as sediment release can cause significant water quality issues and harm to habitats downstream. It is important to note that the reservoir area will initially be unvegetated and will not have any topsoil that can be used to support vegetation growth to control erosion. Additionally, sediments will typically have been deposited in the dam reservoir and are generally very easily remobilised, so this needs special attention from the designers

- flora, fauna and cultural heritage studies – as decommissioning can dramatically alter ecosystems both upstream and downstream, and heritage features can often be highlighted improving the amenity of the new asset. Ecological studies such as flora and fauna assessments are important to identify any threatened species that need to be considered in the decommissioning plans, such as through exclusion zones or timing the works to minimise impacts (e.g. conducting work outside of breeding seasons)

- fluvial geomorphology assessment – which identifies how rivers interact with their landscapes and how they change over time. It is important to understand this given that the decommissioned dam will have water flowing through it rather than retaining water, changing the balance of erosion and sedimentation processes

- dam safety emergency plan for decommissioning works – to protect communities from flooding during the decommissioning works

- regulatory approvals – a dam decommissioning permit will be needed, which will include managing any specific regulatory requirements such as issuing a notice of intent prior to commencing works and providing work-as-executed reports and drawings at the completion of the works to confirm all conditions have been successfully met.

- Depending on the use and location of the dam, it is recommended to consult with a range of stakeholders, including the local community and council, during the planning process to ensure that their perspectives and concerns are considered early. If the dam is located near to residences, public spaces or other civic amenities, extensive consultation is likely to be needed due to the potential nuisance from the works (e.g. noise, dust and additional traffic in the local area). A masterplan can be developed through this process of consultation, outlining potential options for remediating and repurposing the area based on the community’s priorities, such as creating potential new community assets such as wetlands, parks or sporting facilities.

The work involved in decommissioning a dam will depend on the type of dam and the surrounding environment but commonly involves:

- re-routing inflow away from the reservoir or past the dam

- removing all or part of the dam wall

- modifying or removing the outlet works

- lowering the spillway crest level or removing the spillway control gates or stop-boards

- treating retained liquid prior to discharging it in a safe condition

- stockpiling and stabilising accumulated sediments from within the reservoir

- removing or encapsulating impounded material, such as trees and vegetation

- revegetating the reservoir area and rehabilitating the site to perform its new purpose.

Doing it safely

Decommissioning a dam is a very complex matter involving many stakeholders and often taking some time to reach its conclusion, so it is prudent for dam owners to embark early on some interim measures to rapidly reduce any identified dam safety risks. The simplest and most cost-effective risk reduction measure is usually to lower the level of the reservoir.

The next stage is identifying the planning requirements and works involved with decommissioning and developing a decommissioning plan. The engineering design, included in the decommissioning plan, will consider the necessary environmental assessments and ensure adherence to appropriate guidelines.

Common considerations when developing the engineering design include:

- hydrological and hydraulic assessment of conditions before and after decommissioning

- the necessary breach width and batters to make the site safe

- safely discharging or removing retained water and material

- the volume of any attenuated water remaining after decommissioning

- gradient of the land if the reservoir is being completely drained

- erosion and sediment control during and after decommissioning

- managing inflows and floods during the decommissioning

- careful consideration of the final land use after decommissioning including the ecological restoration and community uses.

Achieving success

For decommissioning to be considered successful, it’s crucial that the decommissioning plan and engineering design take account of the priorities that emerge from stakeholder consultation. Many communities become attached to a dam as part of their local landscape, especially if the dam is very old. They may wish for some of the dam’s heritage to be retained or acknowledged in some way, such as retaining and integrating parts of the abutment into the future form or land use where it is safe to do so, or echoing the past by incorporating smaller water features into the resulting site.

Another major consideration for successful decommissioning is controlling erosion and sediment. Reservoirs typically have a low point that can function as a temporary sediment basin once the water level is substantially lowered. Rainfall and inflows can be channelled with small bunds and hessian silt rolls to the sediment basin. Turbid water can then settle or be treated, if necessary, before being pumped out. After decommissioning, erosion and sediment can be managed by revegetating exposed areas with native plants, creating habitat features such as wetlands or log jams, and managing and monitoring wildlife to ensure their adaptation to the changing environment. Simple solutions can be implemented to achieve positive – or at least neutral – outcomes for biodiversity.

Right process, right people

Decommissioning dams takes a wide range of skills to deliver a successful outcome – from hydrology and hydraulics, environmental and heritage assessments, through to detailed construction planning and a vision for the repurposed land. With the right people and process, decommissioning can reduce safety risks to the community, protect the environment during the works, and ultimately create new, sustainable assets enhancing the amenity of the area for the benefit of communities now and long into the future.

Entura has been involved in a number of dam decommissioning projects including Waratah Dam and Tolosa Dam. To talk with Entura’s specialists about a dam decommissioning project, contact Richard Herweynen or Phillip Ellerton.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joey Scicluna is a civil engineer, who began his career managing commercial and subdivision projects. Since joining Entura’s dams and geotechnical team in 2022, he has undertaken a wide range of dam safety surveillance inspections and reporting, dam safety modelling and analysis and risk assessments. Joey has been the lead author for a number of intermediate and comprehensive dam safety reviews, and has developed design concepts and conducted feasibility studies for existing and new dams projects. Joey enjoys problem solving and working with stakeholders to achieve the best outcome for every project.

Risk is the word – reflections on the NZSOLD/ANCOLD 2025 conference

From 19 to 21 November 2025, industry experts from consultants to asset owners gathered in Ōtautahi Christchurch, New Zealand, to exchange insights, challenge thinking and strengthen connections ‘across the ditch’ and beyond. Here Entura’s Sammy Gibbs reflects on the conference …

If I had dollar for every time I heard the word ‘risk’ across the two-day event, I might have been able to fund next year’s conference myself!

Why was this the case? As noted in many of the presentations and papers, the dam industry is facing the combined challenges of aging dam infrastructure, changing design standards, climate change impacts, community expectations and resource/cost constraints. As a result, the industry is shifting more towards risk-informed decision-making/frameworks, compared to traditional standards-based approaches,to manage and design dam infrastructure.

No dam is 100% safe and all risks can never be designed out entirely, but a sophisticated understanding of their risk can inform our decisions and actions so that we can target key issues cost-effectively and ensure resilience in our dams and water infrastructure.

Risks in asset ownership

In his opening address, Andrew Watson, Director of Dam Safety & Generation Asset Planning at BC Hydro in Canada, provided valuable insights into how BC Hydro uses a risk-informed framework to manage its dams. He discussed the use of a ‘vulnerability index’ to understand the significance of identified physical deficiencies in the dam portfolio. The higher the index, the greater the likelihood that the deficiency would result in poor performance. This index allows BC Hydro’s dam safety team to understand the overall risk profile and prioritise future works. It left us contemplating how the ANCOLD 2022 Risk Assessment Guidelines and ALARP process may be enhanced by integrating components of this approach. This could be a useful way of measuring how far the dam is from meeting ‘best practice’ and hence enhance the justification for further risk reduction or accepting the position as ALARP.

Later in the conference, Andrew Watson was joined by Peter Mulvihill, Lelio Mejia and Barton Maher to discuss legacy risk and how to manage it. Legacy risk is relevant for many asset owners (nationally and internationally) as our sector faces the complexities of inheriting aging facilities, acquired from past organisations/owners. A key challenge with these legacy structures is the transfer of knowledge to new asset owners. Important records such as monitoring data, design and construction information are often lost (or were never developed), making it difficult to understand and quantify the current risk position of the structure. These aging facilities are also unlikely to meet current design standards or withstand climate change impacts. Risk-informed decision making and phased approaches become critical in such instances, as does asking the question ‘Does it matter?’ when it comes to unknowns. Like tying surveillance programs to key failure modes, unknowns should also be associated with credible failure modes.

It was noted that for some of these structures the most appropriate solution is decommissioning, as the risk imposed by the structure (and the cost to mitigate it) may outweigh the economic benefit of the asset itself. In such instances, this decision can provide social and environmental benefits and are worth investigating.

Risk in surveillance monitoring

The conference reaffirmed the critical role of risk-based surveillance monitoring and the importance of understanding how dam instrumentation relates to key failure modes and/or performance. The most effective tool to support this is an event decision tree.

Entura’s Diego Real reiterated the importance of understanding key failure modes when implementing instrumentation upgrades. His paper presented a staged approach for the upgrades, providing clients with a cost-effective, practical solution that assists in managing dam safety risks.

Although there was discussion about various ways in which surveillance programs can be optimised, our industry is aligned in recognising the criticality of undertaking routine inspections as the first line of defence when it comes to identifying potential failure indicators.

Risk mitigation solutions

Several presenters shared examples of bespoke solutions responding to dam risks – including Entura’s Jaretha Lombaard, who highlighted how a Swedish berm was used to mitigate risks associated with piping failures at an earth and rockfill embankment dam in Tasmania.

Other risk mitigation solutions presented included non-physical works such as improvements in surveillance and monitoring. In one example, alarm systems in rivers are being used effectively to warn and evacuate the public in a swimming pool downstream in the event of a flood. Instead of relying solely on costly capital-intensive physical upgrades, the most effective strategy for reducing societal risks may lie in enhancing the speed and reliability of early warning systems.

Sharing knowledge to tackle similar problems

NZSOLD/ANCOLD 2025 was an excellent opportunity to see how specialists are tackling the complex challenges facing the dams industry. Walking away, my mind was full of phrases involving the word ‘risk’, but I felt reassured that we are all facing similar problems and by sharing our knowledge and innovations we’re continually improving our ability to design, monitor and maintain dams.

This conference will be a tough act to follow, but I look forward to the 2026 ANCOLD conference to be held in Lutruwita/ Tasmania (where I live and Entura originated).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sammy Gibbs is a civil engineer with 7 years of consulting experience and joined Entura’s Dams and Geotech Team in May 2021. Sammy has a diverse background in dam and water engineering and works on a range of projects including consequence category assessments, hydrology studies, hydraulic design, risk assessments and dam design projects.

Reflections from MYCOLD 2025: Innovation, resilient dams and the evolving role of hydropower

Earlier this month, I had the privilege of joining colleagues from across Malaysia and the region at the 3rd International Conference on Dam Safety Management and Engineering (ICDSME2025), organised by the Malaysia Commission on Large Dams (MYCOLD), held in Kuching, Sarawak. There’s a particular energy that comes with a MYCOLD conference – part reunion, part technical deep-dive, part regional conversation about water, resilience and community safety.

I returned energised and inspired – not only by the technical excellence on display, but also by the sense of shared purpose across our industry and the tangible people-to-people exchanges and collaborations. With energy systems transforming rapidly, climate change accelerating and dam safety expectations strengthening, it has never been more important for dam and hydropower professionals to share openly and learn from one another. ICDSME2025 offered that in abundance.

Here are just a few reflections on some of what I heard …

Reimagining hydropower in changing markets and climates

In the ‘Advancing sustainable hydropower’ session, I shared perspectives from Tasmania’s long hydropower journey and Entura’s experience supporting the state’s major renewable energy initiatives.

My message was clear: the feasibility of pumped hydro or of reimagining conventional hydropower isn’t simply a technical question of ‘can we build it?’ but ‘what is the long-term value it creates?’ Smart choices depend on a holistic understanding of context – i.e. the markets, energy mix, climate, environmental impacts and benefits, and community perspectives and impacts. Pumped hydro is never ‘impact-free’, and it is not inherently more sustainable than conventional hydropower. What matters is how we think about the future of the energy transition, understanding what role pumped hydro can play in that context, how well we select sites, how carefully we consider environmental and social impacts, and how thoughtfully we design (and extend) assets for long-term economic and social value.

With wind and solar dominating new energy investment in Australia, hydropower’s baseload role can shift to respond to evolving market dynamics. Hydropower’s deep storage, flexibility and system stability are becoming increasingly important. We’re seeing these opportunities in Tasmania, where both conventional hydropower and pumped hydro could – with more interconnection to the mainland – help balance a renewables-rich National Electricity Market while returning extra revenue to Tasmania and increasing the reliability of supply across Australia’s south-east.

Climate change adds further complexity to feasibility considerations. Changing rainfall patterns, more variable inflows and more frequent extremes – as well as with the increasingly variable generation mix and how energy sources interact – all influence when hydropower can generate or store.

Ultimately, I believe there are not only opportunities with extending operating life, refurbishing or redeveloping dam assets; there are also obligations upon us as an industry to do our best for the sustainability of these assets. We need to focus constantly on how to optimise outcomes from the base impacts of hydropower or dam developments and seek ways to reduce impacts into the future. We also need to think about how to deliver great outcomes and value that extends across a long asset life, beyond the limited commercial timeframes considered in final investment decisions.

Technology, people and the future of dam safety

I had the honour of chairing a keynote session featuring Yang Berbahagia Prof. Datin Ir. Dr. Lariyah binti Mohd Sidek and Dr Martin Wieland.

Dr Wieland’s insights into the seismic performance of dams reminded us that strong engineering fundamentals remain as crucial as ever, even as digital tools advance. Prof. Lariyah explored how digital platforms, artificial intelligence and risk-based frameworks are shaping the next generation of dam safety practice. She emphasised the importance of the human layer: building institutional readiness, strengthening safety culture, fostering stakeholder trust, and ensuring effective engagement with communities.

Together, their perspectives reinforced that the future of dam safety will depend on both technological innovation and human-centred capability and how effectively these dimensions interact. That’s something Entura is focused on as we continue to bring deep expertise and experience, while exploring and testing the possibilities of new technology to support design and analysis.

Learning from incidents to strengthen global knowledge

Another highlight for me was chairing a session on dam surveillance, monitoring and evaluation. Seven presentations, while different in context and purpose, in combination emphasised the power of data and the importance of learning from experience.

A standout paper examined the 2022 landslide incident at Kenyir Dam, an event that occurred quite soon after Entura’s dam safety inspector training program used the dam as a site visit capstone. Despite extreme rainfall and slope instability, and some damage to appurtenant structures and spillway, instrumentation data confirmed that the dam behaved as designed. What was also clear was that, largely, the instrumentation in place and the data that was able to be collected was a positive demonstration of the importance of robust dam design and monitoring systems.

Another paper explored machine-learning approaches to forecasting short-term reservoir levels at Batang Ai Hydroelectric Project – a scheme with which Entura has long been associated. The results were impressive and point to a future where AI-supported forecasting strengthens real-time operations, especially under increasing climate variability.

These are exactly the kinds of insights our industry must continue to share openly and widely. We can never ‘design out’ all risk, but we can reduce it through good data and continual reflection and learning from real-world events.

Strengthening long-term capability in Malaysia

ICDSME2025 also highlighted the importance of building capability – something I am passionate about. It was encouraging to see Malaysia’s Certified Dam Safety Inspector program, developed with input from Entura’s training arm ECEWI, growing into a sustained and locally led pathway, launched during the conference. Strengthening dam safety ultimately depends on skilled people and strong institutions, making investment in training an investment in long-term sustainability of dam safety governance – and ultimately greater national resilience. We hope to continue to work with MYCOLD to determine how our specialised expertise can further enhance capability uplift beyond surveillance, extending to dam safety risk decision making and dam safety engineering.

A shared commitment to the future

Conferences like ICDSME2025 are timely reminders of our collective responsibility and the shared purpose we need to bring to the challenges ahead. We’re all navigating the same landscape, and when we come together – sharing data, stories and lessons – we accelerate progress for everyone.

I am grateful to MYCOLD for the invitation to contribute and for the generous knowledge-sharing throughout the event. I left Sarawak optimistic: the connection, commitment and collaboration across our sector have never been stronger as we work toward our common goal: safer, more sustainable dams and hydropower systems that support resilient futures.

Can you trust advanced tools without qualified professionals behind them?

To make confident decisions about renewable energy assets – from building a wind farm to monitoring dam performance or optimising asset management – owners and operators need precision data they can trust.

As the renewable energy sector becomes increasingly digitised, the quality of measurements matters more than ever. Digital twins, predictive analytics, AI-driven performance tools and remote operations all depend on reliable, precise and traceable data.

Good data provides visibility. It lets owners and operators detect faults or safety issues early, optimise performance, and protect reliability and revenue. For example, accurate turbine alignment during installation or refurbishment could save hundreds of thousands of dollars in downtime and maintenance.

However, data only provides value if it has the right level of accuracy for the job intended. If the data isn’t up to scratch, the decisions won’t be either.

Keeping pace with technology is a steep learning curve

Surveying has always been the backbone of infrastructure development, land management and industrial precision. From the early days of using theodolites and chains to today’s cutting-edge technologies like laser scanning, UAV photogrammetry and LiDAR, the discipline has evolved dramatically. Yet, one constant remains: the need for appropriately qualified and experienced professionals.

Surveying is far more than measuring distances – and achieving precision requires more than sophisticated instruments. It requires a deep understanding of geodesy, data integrity, error propagation and spatial analysis. Traditional instruments such as theodolites and total stations demand mastery of angular measurement and trigonometric principles. GNSS-based methods introduce complexities like satellite geometry, atmospheric corrections and datum transformations. As technology advances, the learning curve steepens: laser scanners and UAVs generate massive point clouds, while LiDAR systems demand expertise in filtering, classification and 3D modelling.

Surveying principles now extend beyond land and construction into industrial metrology, where precision is measured in microns rather than millimetres. In the renewable energy sector, the applications are vast, from assessing hydropower turbine blade wear and integrity of concrete structures to verifying the verticality of wind turbines and ensuring accurate positioning of new hydraulic equipment. Here, advanced techniques like laser trackers and terrestrial laser scanning dominate, and the margin for error is extremely small.

Precision gives confidence that the data feeding an asset’s digital models is accurate, consistent and aligned with recognised standards. When survey instruments, operational sensors and digital monitoring systems all work within a strong metrological framework, asset owners can be confident that their decisions are based on fact, not noise.

The human behind the technology

However sophisticated today’s measurement tools and technologies may be, their outputs are only as trustworthy as the professionals behind them.

Without properly qualified and experienced operators, advanced tools can become liabilities rather than assets. Misinterpretation of data or incorrect calibration can lead to costly errors in construction, infrastructure alignment or asset management.

Using the wrong technique or sensor for the use case and conditions, neglecting appropriate calibration, and a lack of adequate redundancy can lead to major issues and costly mistakes.

Specialised, qualified professionals will think through these issues early, ensuring that accuracy and tolerance requirements are clearly defined from the start and that data integrity is maintained throughout with robust quality control and assurance procedures.

Human insight provides the environmental and engineering context and assurance that automated systems alone cannot deliver. Surveying and metrology professionals can determine whether readings are valid and offsets are accounted for – and will be able to distinguish genuine change from measurement anomalies.

Ultimately, it is professional judgement that transforms accurate data into actionable insights and confident decisions.

Accuracy drives advantage

Today’s surveying advances are transforming how decisions are made. Spatial data is no longer just a technical input; when validated and interpreted by qualified professionals, it becomes a valuable source of real strategic insight and advantage. When the data is right from the start, every subsequent step becomes more certain and the outcomes have the best chance of being more efficient and sustainable. Such clarity can be the difference between success throughout an asset’s lifecycle and expensive lessons learned.

As technologies advance, so does the need for qualified professionals who understand both the science of measurement and the realities of complex, dynamic infrastructure. By ensuring accuracy, compliance with standards and efficient workflows, the qualified surveyor safeguards projects from financial and reputational risks – enabling the reliability, safety and commercial confidence that every asset owner depends on.

If you’d like to talk to us about the potential of advanced surveying and metrology on your project, contact Phillip Ellerton or a member of our Spatial & Data Services Team.

How hydropower history and innovation can continue to power progress

Having been named as the Planning Institute of Australia’s Young Planner of the Year for 2024 and awarded a bursary, Entura’s Bunfu Yu travelled through Switzerland and France to study hydropower and energy innovation. Her reflections from the study tour highlight how history-rich hydropower assets can continue to evolve and add value in a changing world …

Switzerland’s Ritom hydropower project – which is in the late stages of a major redevelopment and anticipated to be operational later in 2025 – is a technical marvel of the past and the present. It is also a lesson in how energy infrastructure can evolve while still respecting its historical roots.

The original Ritom power station was commissioned in 1920 as part of a traditional hydropower scheme using water from Lake Ritom to generate electricity. It holds a special place in Swiss energy history as the first plant to supply electricity to the Gotthard railway, which is a vital north–south transit corridor through the Alps. This early integration of hydropower with transport infrastructure helped shape the modern Swiss energy landscape.

However, after more than a century of faithful service, Ritom’s aging infrastructure and the region’s changing energy needs prompted a major rethink.

Modernising with purpose

Ritom is undergoing a major transformation to meet 21st century demands. The redevelopment project involves replacing the historic hydropower plant with modern facilities and converting it from a conventional hydropower scheme to include a pumped hydropower component. By using two existing lakes (Lake Ritom and Lago di Cadagno) as the upper and lower reservoirs, energy can be stored by pumping water uphill during periods of low demand and releasing it to generate electricity when demand peaks. This is critical for maintaining reliability and stability in today’s dynamic grid. The lakes are also popular with walkers, and this recreational value will continue alongside the repurposed scheme.

The revamped facility will increase capacity to 120 MW, improving energy resilience for both the local Ticino region and the Swiss Federal Railways. The upgrade enhances energy security and does so with a strong emphasis on environmental and community values.

Balancing environment, engineering and community

Like all major infrastructure projects, Ritom has complexities. A key concern is managing downstream water flow to protect river ecosystems. To address this, the project incorporates a demodulation basin – an engineered feature that moderates flow variations, preserving the ecological health of the river below.

Minimising disruption for the local community during construction has also been a priority. This has taken careful management, as the project is nestled between the alpine villages of Piotta and Piora. The project team constructed a dedicated cableway to move heavy materials – such as massive steel penstocks – away from narrow local roads. This solution reduced construction traffic and helped preserve the peace and safety of surrounding communities.

Ritom is an inspiring example of how infrastructure can evolve when regulators, engineers and communities work together. Innovative thinking coupled with flexibility in permitting has enabled tailored solutions that are practical and environmentally sound – an approach that is replicable worldwide.

Technical excellence delivering long-term social value

Ritom reminds us that great infrastructure is more than engineering and functionality – it can inspire and be enjoyed.

Each year, the region celebrates the connection between nature, people and infrastructure through the ‘Stairways to Heaven’ race – a brutal yet iconic event that ascends 4,261 steps alongside the original penstocks of the Ritom scheme. With an average 89% incline over 1.2 km, it is Europe’s steepest race, attracting elite athletes as well as daring locals. The climb is physically punishing, but those who reach the summit are rewarded with breathtaking panoramic views of the Swiss Alps and the glistening Ritom reservoir.

This race is more than a sporting challenge. It is a symbol of how infrastructure can become deeply woven into the identity of a community, engendering enduring pride and delivering long-term social value well beyond its technical purpose.

The Ritom project is a powerful reminder that the future of energy lies in more than technology alone, but in how we carefully and intentionally navigate the intersections and synergies of history, environment and communities.

Planning for progress

Redeveloping or repurposing long-standing hydropower assets demands more than engineering expertise – it requires sensitivity to contemporary expectations. Since many of these projects were first built, the regulatory environment has shifted dramatically, with much greater emphasis on biodiversity protection (terrestrial and aquatic), climate resilience, the voices of local communities, and the cultural and heritage values of the Country on which these projects have been developed. The best projects don’t treat these as hurdles, but as opportunities to build broader value into the asset’s future.

Making good decisions at the earliest stages of refurbishment, repurposing or redevelopment is critical. To ensure lasting benefits, projects will need clear strategies grounded in sound technical evidence and shaped by a strong understanding of regulatory requirements and community expectations. Long-term success is more likely when projects are not only viewed through the technical lens of extending asset life, but are reimagined with community and environment at their core. Hydropower projects such as these can be catalysts for long-term energy security, greater ecological stewardship, strengthened social outcomes, and even become a source of community pride and inspiration.

In Australia, Entura is working with Hydro Tasmania to apply these principles through our work on the redevelopment of the Tarraleah hydropower scheme, parts of which are more than 80 years old. The redevelopment aims to increase capacity and flexibility so that Tarraleah can better serve the needs of the changing energy market – and future generations. It’s a project that echoes Ritom’s lesson: that heritage and innovation can coexist to create modern, sustainable infrastructure with value that endures for generations. By striking the right balance, hydropower can continue to do what it has always done best – power progress – while also meeting the needs and values of communities and environments today and long into the future.

Bunfu (above left) thanks Lombardi Engineering Switzerland for organising a comprehensive on-site tour of the Ritom hydropower project.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bunfu Yu is a dynamic young leader in renewable energy planning, approvals, and business development. Bunfu played a pivotal role in Entura’s Environment and Planning Team’s success in achieving the Planning Institute of Australia’s National Award for Stakeholder Engagement in 2024. In 2023, Bunfu was named the National Young Planner of the Year by the Planning Institute of Australia. This honour recognised not only her passion for the planning and delivery of renewable infrastructure but also her active contribution to the profession through mentoring, public engagement, and knowledge sharing. She is currently a Senior Environmental Planner and a Business Development Manager at Entura, having joined the business as a Graduate Planner in 2018.

‘Dams for People, Water, Environment and Development’ – some reflections from ICOLD 2024

Entura’s Amanda Ashworth (Managing Director) and Richard Herweynen (Technical Director, Water) recently attended the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD) 2024 Annual Meeting and International Symposium, held in New Delhi. Amanda presented on building dam safety capability, skills and competencies, while Richard presented on Hydro Tasmania’s risk-based, systems approach to dam safety management, and the importance of pumped hydro in Australia’s energy transition.

Here they share some reflections on ICOLD 2024 …

Richard Herweynen – on the value of storage, ‘right dams’, and stewardship

At ICOLD 2024 we were reminded again that water storages will be critical for the world’s ability to deal with climate change and meet the growing global population’s needs for food and water. We can expect greater climate variability and therefore more variability in river flows, which means that more storage will be needed to ensure a high level of reliability of water supply. Without more water storages to buffer climate impacts, heavily water-dependent sectors like agriculture will be impacted.

To slow the rate of climate change, we must decarbonise our economies – but without significant energy storage, it will be difficult to transition from thermal power to variable renewable energy (wind and solar). Pablo Valverde, representing the International Hydropower Association (IHA), said at the conference that ‘storage is the hidden crisis within the crisis’. There was a lot of discussion at ICOLD 2024 about pumped hydro energy storage as a promising part of the solution. It is also important, however, to remember that conventional hydropower, with significant water storage, can be repurposed operationally to provide a firming role too. Water storage is the biggest ‘battery’ of the world and will be a critical element in the energy transition.

With the title of the ICOLD Symposium being ‘Dams for People, Water, Environment and Development’, I reflected again on the need for ‘right dams’ rather than ‘no dams’. ‘Right dams’ are those that achieve a balance among people, water, environment and development. In the opening address, we were reminded of the links between ‘ecology’ and ‘economy’ – which are not only connected by their linguistic roots but also by the dependence of any successful economy on the natural environment. It is our ethical responsibility to manage the environment with care.

When planning and designing water storages, we must recognise that a river provides ecological services and that affected people should be engaged and involved in achieving the right balance. If appropriate project sites are selected and designs strive to mitigate impacts, it is possible for a dam project’s positive contribution to be greater than its environmental impact, as was showcased in number of projects presented at the ICOLD gathering. Finding the balance is our challenge as dam engineers.

The president of ICOLD, Michel Lino, reminded delegates that the safety of dams has always been ICOLD’s focus, and that there is more to be done to improve dam safety around the world. At one session, Piotr Sliwinski discussed the Topola Dam in Poland, which failed during recent floods due to overtopping of the emergency spillway. Sharing and learning together from such experiences is an important benefit of participating in the ICOLD community.

Alejandro Pujol from Argentina, who chaired one of the ‘Dam Safety Management and Engineering’ sessions, reflected that in ICOLD’s early years the focus was on better ways to design and construct new dams, but the spotlight has now shifted to the long-term health of existing dams. It is critical that dams remain safe throughout the challenges that nature delivers, from floods to earthquakes. In reality, dams usually continue to operate long beyond their 80–100 year design life if they are structurally safe, as evidenced in the examples of long-lived dams presented by Martin Wieland from Switzerland. He suggested that the lifespan of well-designed, well-constructed, well-maintained and well-operated dams can even exceed 200 years. As dam engineers, no matter the part we play in the life of a dam, we have a responsibility to do it well.

From my conversations with a number of dam engineers representing the ICOLD Young Professional Forum (YPF), and seeing the progress of this body within the ICOLD community, I believe that the dam industry is in good hands – although, of course, there is always more to be done. I was pleased to see an Australian, Brandon Pearce, voted onto the ICOLD YPF Board.

Another YPF member, Sam Tudor from the UK, reminded us in his address of the importance of knowledge transfer, the moral obligation we all have especially to the downstream communities of our dams, and our stewardship role. He was referencing his experience of looking after dams that are more than 120 years old – all built long before he was born. Many of our colleagues across Entura and Hydro Tasmania feel this same sense of responsibility and pride when we work on Hydro Tasmania’s assets, which were built over more than a century and have been fundamental to shaping our state’s economy and delivering the quality of life we now enjoy. It is up to all of us to carry the positive legacy of these assets forward with care and custodianship, for the benefit of future generations.

Amanda Ashworth – on costs and benefits, dam safety, and an inclusive workforce

Like Richard, I found much food for thought at ICOLD 2024. For me, it reinforced the need to accelerate hydropower globally, particularly in places where the total resource is as yet underdeveloped. To do so, we will need regulatory frameworks that support success – such as by monetising storage and recognising it as an official use – and administrative reforms that ease the challenges of achieving planning approvals, grid connection agreements and financing for long-duration storage. We must encourage research and development to move our sector forward: from multi-energy hybrids to advanced construction materials and innovations to improve rehabilitation.

In particular, I’ve been reflecting on how our sector could extend our thinking and discourse about the impacts and benefits equation beyond the broad answer that dams are good for the net zero transition. How can we enact and communicate the many other potential local environmental and social benefits and long-term value from dams?

Much of the world’s existing critical infrastructure came at a significant financial expense as well as social and environmental costs – so it is our obligation to pay back that investment by maximising every dam’s effective life. When we invest in extending the lifespan of dam infrastructure through effective asset management and maintenance, and when we maximise generation or the value of storage in the market, we increase the ‘return on investment’ against the financial, social and environmental impacts incurred in the past.

Of course, the global dams community must continue to prioritise dam safety and work towards a ‘safety culture’. I was pleased to hear Debashree Mukherjee, Secretary of the Ministry of Jal Shakti, celebrate the progress on finalising regulations across states to enact India’s Federal Dam Safety Act and establishing two centres of excellence to lift capacity across the nation. Dam safety depends on well-trained people with the right skills and competencies to comply with evolving standards, apply new technologies, and respond effectively to changing operational circumstances and demands.

I also enjoyed hearing from ICOLD’s gender and diversity committee on its progress, including updates from around 14 nations on their efforts to build a more inclusive renewable energy and dams workforce. This is front of mind for us, as we step up Entura’s own focus and actions on gender equity throughout our business this year.

The challenges facing our dams community – and our planet – are enormous, but there is certainly much to be excited about, and we look forward to continuing these important conversations over the next year.

From Richard, Amanda and Entura’s team, many thanks to the Indian National Committee on Large Dams (INCOLD) for organising and hosting this year’s ICOLD event, supporting our sector to build international professional networks, and facilitating the sharing of experiences and knowledge across the globe – all of which are so important for growing the ‘ICOLD family’ and supporting a safer, more resilient and more sustainable water and energy future.

Growing the future of hydropower – observations from a career in the industry

Entura’s Senior Principal Hydropower, Flavio Campos, knows hydropower inside out. Flavio has recently joined Entura, after working around the world on significant hydropower projects ranging from 30 MW to a whopping 8,240 MW. We asked him to share some of his hydropower journey, what excites him about the future of the sector, and what’s different about conventional hydropower and pumped hydro in supporting the clean energy transition …

When I immigrated from Brazil to Canada in 2012, it was no accident that I settled in Ontario, near Niagara Falls. I had taken a job with a consulting firm that had a hydropower hub strategically located in the Niagara region due to its long history of hydropower.

The Niagara region is the home of the Adams Power Plant, completed in 1886 – the first alternating current (AC) power plant built at scale, delivering an installed capacity of 37 MW at 2,200 V. The voltage is stepped up by a transformer to 11,000 V, allowing for an economic transmission line reaching to the city of Buffalo, NY, 32 km away. The concept was launched by engineer Nikola Tesla in collaboration with George Westinghouse, beating Thomas Edison’s bid, which was based on a direct current (DC) system. Tesla’s dream of harnessing the awesome power of Niagara Falls was realised by the end of the 19th century, when hundreds of small hydropower plants emerged and multiple forms of electricity utilisation spread across the world.

The hydropower boom, led by Brazil and China

When I started my career in the hydropower industry in 1995, I could feel the ongoing impact of the great hydropower boom that was led by Brazil and China through the 1970s and 1980s. In 1999, I was construction manager for Tucurui Dam, one of the biggest hydropower plants in Brazil and the world at that time (now ranked 8th in the world), delivering a total installed capacity of 8,240 MW. As part of my role, in order to raise production to the expected rates, I was able to visit China’s Three Gorges Dam during construction and learn about their techniques and massive concrete operations.

In the 1990s, Brazil’s hydropower industry had plenty of experienced professionals, from construction trading foremen and general superintendents to highly educated engineering professionals from whom I had the privilege to learn.

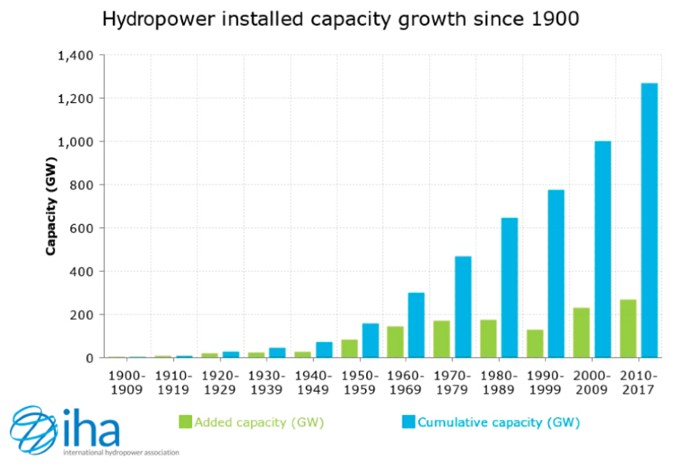

Since those glorious decades, global hydropower capacity has increased significantly. The strongest period was 2007 to 2016, when more than 30 GW was added per year on average. Since 2017, the industry has slumped to only 22 GW per year on average, with only 13.7 GW installed in 2023. However, it is interesting that of the new 13.7 GW, 6.5 GW was delivered as pumped hydro energy storage.

A new wave of pumped hydro

At a HydroVision International conference in Portland, Oregon, in 2019, I noticed that pumped hydro was a significant topic of discussion. The conference highlighted several factors making pumped hydro projects attractive for the clean energy transition: the ‘battery’ feature itself which helps to balance supply and demand, its contributions to grid stability, its lower environmental impact compared to conventional hydropower, the availability and efficiency of variable-speed units, and the cost comparison against other types of batteries.

Projections of a new wave of pumped storage soon evolved from conference coffee-break chatter to reality: in 2022, more than 10 GW of pumped hydro was delivered, the most ever achieved by the industry. Most of this has been delivered in China, where top-down policies imposed by government can deliver rapid results. Other countries operating on a more open-market basis need to improve the mechanisms to foster pumped hydro so that it can support the grid effectively as other variable renewable energy (VRE) sources, such as wind and solar, proliferate.

There is now consensus that pumped hydro is a necessity for grids to cope with increasing amounts of VRE– and the need is urgent. Pumped hydro, however, requires significant upfront investment in civil works and time to implement. Studies by the IHA indicate that besides the inherent need for additional pumped storage in the grid, the world’s conventional (non-pumped) hydropower installed capacity must double by 2050 in order to achieve net-zero transition targets. This will be challenging, given such a low level of new hydropower worldwide in recent years, and the fact that the most attractive sites have been already developed.

There is also opportunity to re-imagine existing conventional hydropower plants to make the most of their natural battery and firming potential – by operating flexibly to support firming VRE rather than generating for maximum volume. Even where there is no market mechanism to specifically monetise this value, it could be rewarded for national or regional outcomes.

How can we achieve the much-needed growth in conventional hydro and pumped hydro?

Conventional (non-pumped) hydropower has long been recognised for clean energy and the long life of the infrastructure. The challenge now is to identify, gain approvals and sustainably deliver new projects in a world where human occupation is growing fast and reaching into the most remote corners of watersheds. Governments and regulators must assess cost benefits against the social and environmental impacts before giving the green light to new hydropower projects.

Developing pumped hydro can be more flexible, especially when it is a closed-loop system that doesn’t depend on water flows, except for first-time filling and for topping up the losses caused by evaporation. Pumped hydro is not new – in fact, it has existed for more than a century. What is new, however, is the challenge of fostering pumped hydro development at the rate needed.

The IHA has helped clarify what is needed for the industry to develop pumped hydro faster. The IHA’s Guidance Note delivers recommendations to reduce risks and enhance certainty, supporting market players to better understand the issues.

Another interesting initiative in the hydropower journey is XFLEX Hydro, a European initiative which brought together 19 entities such as IHA, EDP, EDF, Alpiq, Bechtel and others, with the objective of increasing hydropower capabilities and flexibility to cope with changing grid profiles. X-Flex has launched 7 pilot projects already – and 4 of these are pumped hydro. This combined initiative has illustrated two important areas of focus that can benefit market players and accelerate uptake:

- The need for a supportive regulatory regime: Policy-makers and other stakeholders need to facilitate the development of regulations or market mechanisms that fairly compensate pumped hydro, as well as conventional hydropower, such as ‘price cap and floor’ mechanisms, compensation for stability features provided by hydropower, and expediting the approval process while ensuring that social and environmental impacts are minimised and mitigated.

- The advantages of evolving technologies, including:

- variable-speed units, increasing flexibility

- hydraulic short-circuit operation, in which the plant can pump and generate simultaneously

- hydro/battery hybrid system, in which the battery works along with hydropower and enhances plant flexibility

- digital/AI control platforms, which can improve the overall grid efficiency and reduce downtime.

Hydropower for a better future

The challenges of rapidly building out new conventional hydropower and pumped hydro are huge. Yet, where there is a will, there is a way. Those of us who understand and believe in the benefits of conventional hydropower and pumped hydro have a duty to bring communities along on the journey and to help build a better future for the next generations.

We look forward to bringing you more of Flavio’s insights into conventional hydropower and pumped hydro in future articles. Flavio is currently contributing to a number of Entura’s assignments including supervising construction on the Genex Kidston PHES project in Queensland, for which Entura is the Owner’s Engineer, and being a key adviser on the Tarraleah upgrade as part of Hydro Tasmania’s Battery of the Nation program.

Dams are crucial to climate change response and the energy transition

At the recent ICOLD meeting in Gothenburg, Sweden, dam engineering experts from across the globe came together to share knowledge, discuss trends and issues, and engage with each other. One important topic of discussion was the role of dams in the international response to climate change and what that will mean for the dams industry. Richard Herweynen, Entura’s Technical Director, Water, shares his thoughts on this topic here …

Why will dams play a critical role?

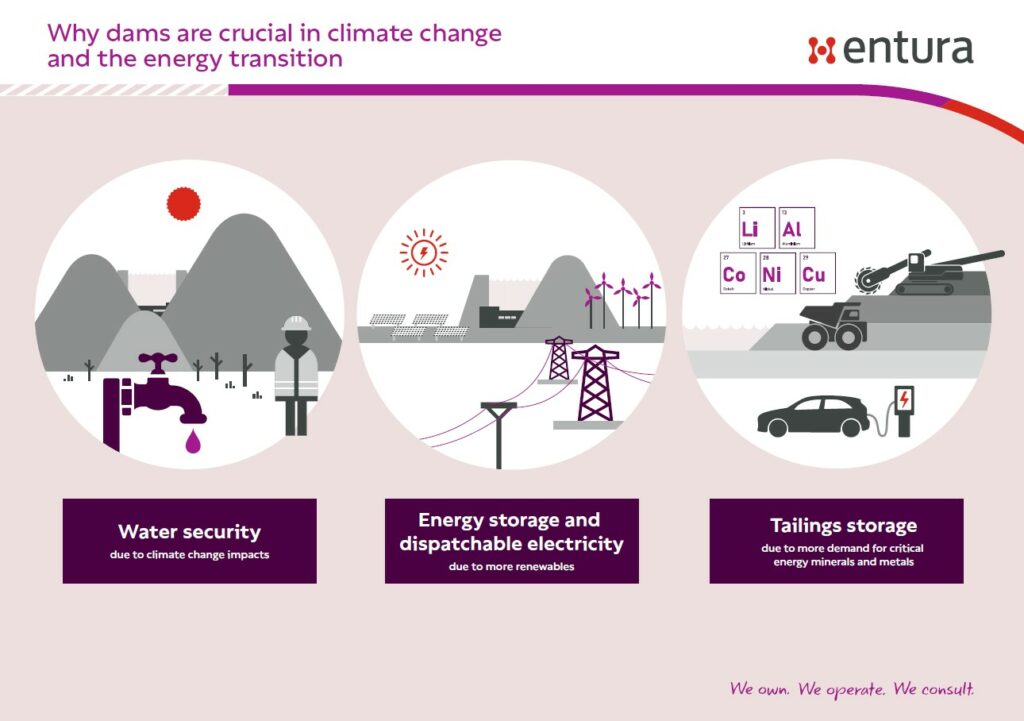

Three major reasons why dams will be crucial in the climate change response and energy transition are water security, dispatchability of electricity, and tailings storage.

- Water storages will be vital to provide the same level of water security

Water security is essential for humanity. With greater hydrological variability due to climate change, more storage will be needed to provide the same level of security of water, food and energy. Water storage is a fundamental protection from the impacts of a changing climate, safeguarding the supply of water, and the water–food–energy nexus, even during extended drought.

The effects of climate change are predicted to increase and to result in greater magnitude and frequency of hydrological extremes, such as prolonged droughts and significant floods. With prolonged drought, inflows to storages will reduce. If demand remains the same, stress on existing water storages will increase.

Water storages are used to regulate flows and manage this variability: storing water when there are high inflows (or floods) and then using this stored water during low inflows (or droughts). Dams are used to create these vital water storages.

- Hydropower and pumped hydro energy storage (PHES) are critical for the energy transition

A key response to climate change is the decarbonisation of the electricity sector through renewable energy. Wind and solar power now offer the lowest cost of energy, have low ongoing operational costs, and emit the least greenhouse gases across their lifecycle – and therefore hold the greatest potential for rapid decarbonisation of the energy sector. Of course, wind and solar PV output vary according to the weather and the time of day – but the electricity market needs the supply of electricity to match demand, or for these renewables to be dispatchable.

Energy storage is the key to smoothing out the variability of renewable energy generated by solar and wind. The power and duration of the storage are the two key variables in determining the most suitable solution. Low-power, short-term storage is currently more cost-effective using batteries, but longer periods and larger power requirements are likely to rely on bigger storage options, such as pumped hydro energy storage (PHES) and traditional hydropower. Smoothing out the daily variability in renewables can be achieved effectively through pumped hydro. Dams are used to create the water storages used in both traditional hydropower and PHES.

- The transition to renewables will demand more minerals and metals

The global energy transition will demand a major increase in renewable energy technologies – which in turn will require more of the ‘critical energy minerals’ and metals. The rising need for minerals such as copper, aluminium, graphite, lithium and cobalt will not be able to be met by recycling and reuse alone. Therefore, extraction and storage of minerals from mining operations will be essential to sustain the renewable energy transition.

According to a report by the World Bank Group, the production of minerals such as graphite, lithium, and cobalt could increase by nearly 500% by 2050 to meet the escalating demand for clean energy technologies. It is estimated that over 3 billion tonnes of minerals and metals will be necessary for the deployment of wind, solar, geothermal power and energy storage, all of which are vital for achieving a sustainable future with temperatures below 2°C.

However, this need for mining activity comes with a special responsibility for sustainable practices, including the proper management and storage of mining waste. Rock, soil and other by-products are left behind after the desired minerals have been extracted from the ore. Tailings facilities store this waste, playing a crucial role in mitigating the environmental impact of mining operations. Dams, in particular, are commonly used to create these facilities, as they provide an effective means of containing the waste.

Dams used in tailings facilities are designed to withstand the weight and pressure of the waste materials, prevent seepage of contaminants into the surrounding environment, and take into account factors such as stability, erosion control and water management. Dams that are well designed, constructed and monitored, adhering to stringent environmental and safety regulations, can help prevent the spread of mining waste into nearby water bodies, reducing the risk of water contamination and protecting aquatic ecosystems.

Working towards ‘good dams’

While there have certainly been some examples around the world of dams that have had adverse impacts, it is clear that dams will play a critical role in the international response to climate change and the decarbonisation of the energy sector. It’s therefore vital that dams are planned, constructed and managed appropriately and safely. With increasing understanding of impacts and far greater sophistication of internationally accepted sustainability protocols, it is now up to developers and planners to heed the lessons of the past and find the right dam sites for nature and communities.

It is important that we ensure the safety of existing dams as well as the safety of any new dams. Examples from around the world demonstrate the devastating consequences of dam failures. Safety must be every dam owner’s key concern, and should be managed through an active dam safety program.

Of course, the larger the portfolio of dams an owner is managing, the greater the demand on their resources; however, it is critical that dam safety risks for water storages and tailings facilities are managed appropriately across dam portfolios to protect downstream communities. The Portfolio Risk Assessment process increases the focus on potential failure modes and risk as drivers of the dam safety program and as the basis for deciding priorities for allocating operational and capital resources.

It will also be vital that dams engineers, owners and operators keep up to date with the latest developments in the dams industry worldwide through continuous learning and important global forums such as ICOLD.

If you’d like to talk with Entura about your water or dam project, contact Richard Herweynen.

About the author

Richard Herweynen is Entura’s Technical Director, Water. Richard has three decades of experience in dam and hydropower engineering, and has worked throughout the Indo-Pacific region on both dam and hydropower projects, covering all aspects including investigations, feasibility studies, detailed design, construction liaison, operation and maintenance and risk assessment for both new and existing projects. Richard has been part of a number of recent expert review panels for major water projects. He participated in the ANCOLD working group for concrete gravity dams and is the Chairman of the ICOLD technical committee on engineering activities in the planning process for water resources projects. Richard has won many engineering excellence and innovation awards (including Engineers Australia’s Professional Engineer of the Year 2012 – Tasmanian Division), and has published more than 30 technical papers on dam engineering.

MORE THOUGHT LEADERSHIP ARTICLES

Planning sustainable water infrastructure in a changing world

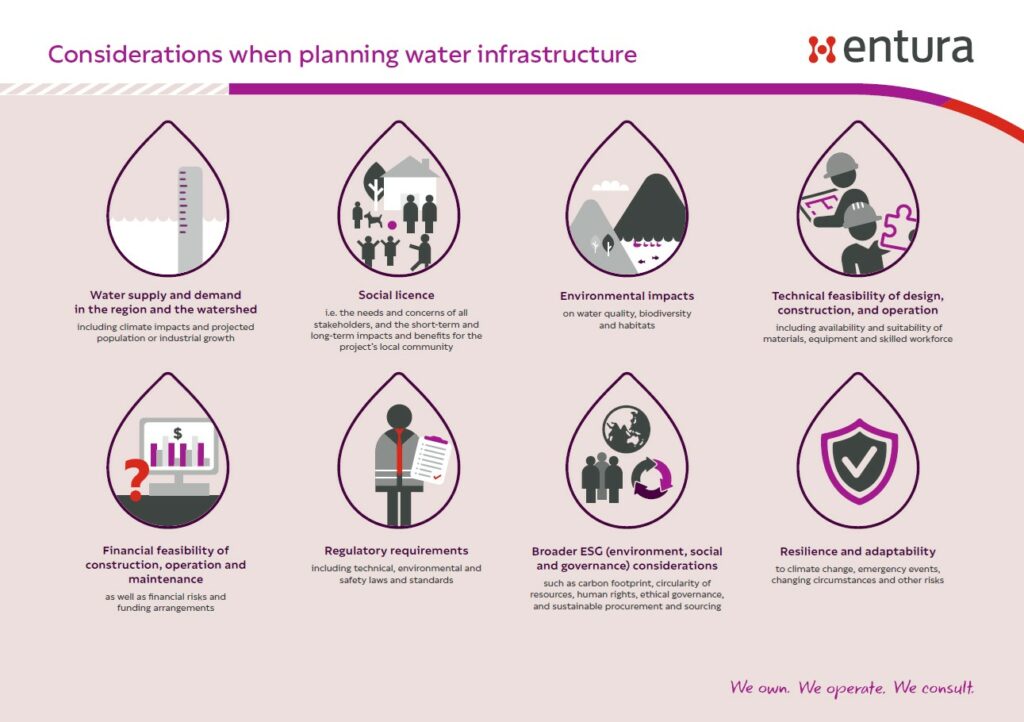

In an already water-stressed world and a rapidly changing climate, water is increasingly precious. To manage and control this vital resource, we must create and maintain safe, reliable and sustainable water infrastructure – and such a challenge calls for good planning.

The International Commission on Large Dams is working towards releasing new guidance for water infrastructure planning – and Entura’s Richard Herweynen is a member of the Technical Committee looking to develop a new ICOLD Bulletin on planning. In this article, Richard explains the importance and evolution of planning approaches.

Water infrastructure projects deliver the dams, treatment plants, irrigation systems and distribution networks that provide water for homes, food production, industries and emergencies. They also create the structures integral for mitigating the effects of floods and droughts. But to maximise the benefits of this infrastructure, projects must be planned, engineered and managed for effectiveness, safety and sustainability.

These projects are far too important to approach in a haphazard way. Planning offers a structured, rational approach to solving problems – and it is the start of the ‘pipeline’ for addressing water resource needs and competing demands. In fact, for civil works programs, everything begins with planning.

Without a good plan, where are we?

Without careful planning, it can be difficult to achieve creative, cost-effective solutions to water needs. The planning stage helps decision-makers identify water resource problems, conceive solutions and evaluate the inevitably conflicting values inherent in any solution. Planning is best done by a team that brings together specialists in many of the natural, social and engineering sciences.

At the planning stage, all of the following points should be thought through:

Guidance for better planning

In 2007, I became the ANCOLD-nominated member on a new Technical Committee for the International Commission of Large Dams (ICOLD) entitled ‘Engineering Activities in the Planning Process for Water Resource Projects’. In 2009 we put forward a position paper setting out an ‘Improved Planning Process for Water Resource Infrastructure’ based on ‘comprehensive vision based planning (CVBP)’.

At the next ICOLD Annual Meeting in Sweden in June 2023, our committee will be meeting to work on an updated framework that takes into account the rapid change we’ve witnessed over the last decade and the many cross-cutting issues that are impacting the planning process, such as risk-informed decision-making, climate change, sustainable development, environmental concerns, and river basins/systems.

What is ‘comprehensive vision-based planning’ (CVBP)?

Before we talk about updates, let’s take a quick look at our existing approach to CVBP, as articulated in 2009.

CVPB is a comprehensive, transparent planning process based on a shared vision for sustainable water resource development. It aims to achieve a better ‘triple bottom line’ outcome, with optimum economic, social and environmental outcomes.

Whereas many past projects were planned on a case-by-case basis, CVBP looks beyond the immediate project to the broader regional vision and watershed goals (which may also cross national borders), taking projected changes in water supply and demand into account. It draws on integrated water resources management (IWRM) to consider multiple points of view about how to manage water and to view each water infrastructure project in relationship to the other existing infrastructure in the region.

CVPB also incorporates much greater attention to the realistic options and cost-benefits of mitigation of environmental impacts – and it draws in more interdisciplinary engineering, cost estimating, and stakeholder/community engagement.

CVBP is, therefore, a holistic, integrated and collaborative approach to planning and a much-improved pathway towards successful outcomes.

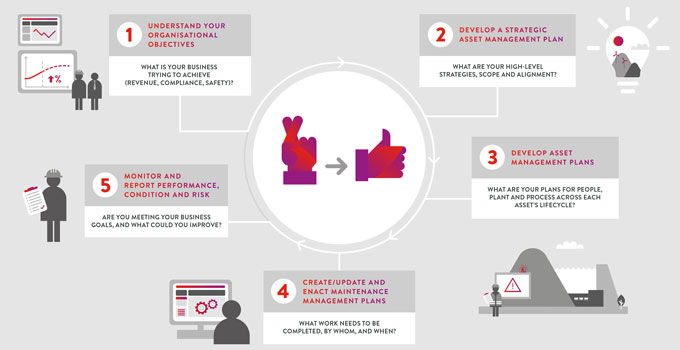

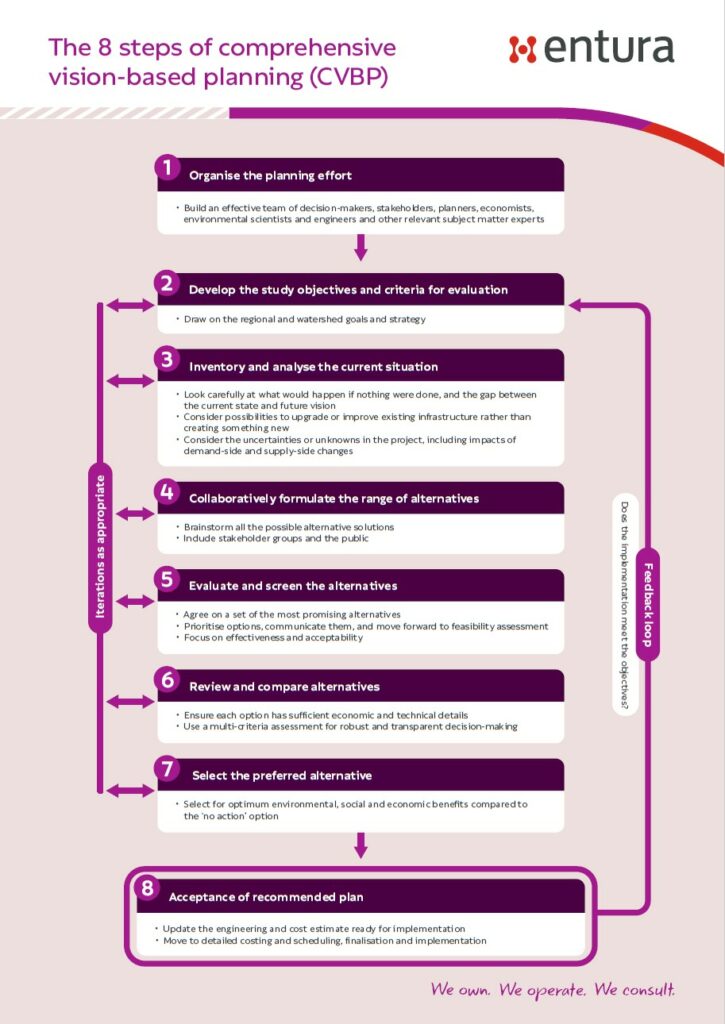

The 8 steps of CVBP

As currently articulated, CVBP has 8 defined steps – but it’s an iterative process in which steps 2 to 7 are repeated multiple times, as necessary. The 2009 ICOLD bulletin goes into much greater detail than we can in this article, but this will give you an overview:

Changes moving forward

It is time to update the planning process and guidance in the light of the rapid changes we are experiencing in our environment, innovations in technologies, and an increasing awareness of sustainability and ethics.

In the past, much water infrastructure has been planned within a reasonably near-term political and social lens and timeframe, and from a perspective of relative stability. But we know that change is constant and rapid, so our planning approaches need to shift to an even greater appreciation of uncertainty, risk and the intensifying potential for extreme events. There is also an urgent need to apply a deeper and broader awareness of the many considerations that make for greater environmental, social and economic sustainability.

Important factors here will be an uplift in stakeholder involvement and governance, a very clear focus on the costs and benefits that can’t easily be quantified or monetised, and reinforcement of the fundamental principle of ‘do no harm’.

It will also be important to take an adaptive approach to regional planning objectives, with a strong awareness of different regional and cultural values, goals, expectations, methodologies, financing arrangements and roles of government.

We should expand the planning scenarios to also explore non-structural options, dam removal plans, and scenarios based on failure modes. We also need to improve early data collection by finding and filling data gaps, improving the ways in which we preserve historical information, and improving data portrayal.

It is very important to involve the right people. Ideally, the planning team should be more than ‘multi-disciplinary’ or ‘interdisciplinary’. It should aspire to be ‘transdisciplinary’, in which all disciplines work seamlessly and collectively and achieve a level of insight that is ‘greater than the sum of its parts’.

This year, our Technical Committee will continue to build on some of these elements as we review and rearticulate CVBP, working towards a new ICOLD Bulletin to guide water infrastructure planning.

In a changing world, our approaches to infrastructure cannot stagnate. Designing, articulating and applying new planning frameworks is an important step towards creating and maintaining the sustainable, reliable water infrastructure our planet so urgently needs.

If you’d like to talk with Entura about your water or dam project, contact Richard Herweynen.

About the author

Richard Herweynen is Entura’s Technical Director, Water. Richard has three decades of experience in dam and hydropower engineering, and has worked throughout the Indo-Pacific region on both dam and hydropower projects, covering all aspects including investigations, feasibility studies, detailed design, construction liaison, operation and maintenance and risk assessment for both new and existing projects. Richard has been part of a number of recent expert review panels for major water projects. He participated in the ANCOLD working group for concrete gravity dams and is the Chairman of the ICOLD technical committee on engineering activities in the planning process for water resources projects. Richard has won many engineering excellence and innovation awards (including Engineers Australia’s Professional Engineer of the Year 2012 – Tasmanian Division), and has published more than 30 technical papers on dam engineering.

MORE THOUGHT LEADERSHIP ARTICLES

Field investigations in remote locations – factors for success

Conducting field investigations in remote areas is no ‘walk in the park’. On top of the investigation activities themselves, there are the complex logistics of getting personnel and equipment into hard-to-reach places, the imperatives of maintaining safety and managing community expectations, and the significant challenge of conducting works but leaving minimal impact on the landscape.

‘Leave no trace’ may not be too hard a goal when you’re heading off on a simple bushwalk. However, when it comes to conducting field investigations in remote areas with heavy specialist equipment, ‘treading lightly’ can be extremely challenging – but it is something Entura is committed to.

Entura has recently delivered geotechnical investigations for Hydro Tasmania’s feasibility study into the potential for pumped hydro development in some very rugged, remote country in western Tasmania. This is how we did it, and some success factors we can share for field work in these conditions.

Planning

Planning and contract expertise is paramount for successful execution of any project, but particularly so in remote locations. It’s important to take the time at the very beginning of a project to really understand the entirety of the scope and the project objectives. To reduce the risk of unwelcome surprises and unwanted variances, spend enough time on the ground before the works commence so that you can be sure that all the elements have been considered.

This is also the time to gain a full understanding of all the permits and approvals that will be required, the lead time to achieve them, and the range of agencies and key stakeholders who need to be engaged right from the earliest stages.

It will take time and consideration to engage carefully with all contractors to understand their expertise, capability and willingness to undertake the works; but the effort to find the right contractors will be more than repaid by the improved outcomes.

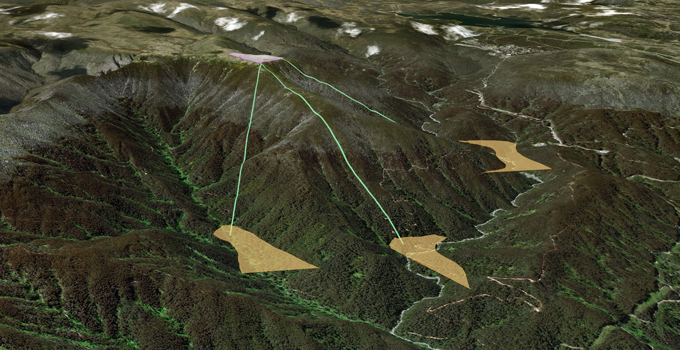

Our project involved multiple drilling investigations to 600 m in 3 separate and remote locations, including a deep ravine located between Lake Plimsoll and Lake Murchison in the heart of Tasmania’s West Coast. The goal was to achieve a clear understanding of geological conditions within the region, which had previously been identified as a fault zone. Our planning needed to encompass all the necessary desktop studies to understand as much as possible about the environment, the stakeholders, the regulations and requirements, and the conditions our contractors could expect, all in advance of sending personnel and equipment into the remote site.

The key to our success in the project was leaving no stone unturned in the planning phase, and using these preliminary insights to choose the right contractors for the job, with the right equipment and skills to achieve our objectives. When things go smoothly and look seamless or simple from the outside, it is usually because of the significant investment of effort in detailed, logical planning right at the start.

Site access

Remote access can be extremely difficult, so the success of a project will depend on establishing practical, efficient and low-impact routes at the earliest stages of planning. Time is money, so contractors will need the easiest and quickest access to the site that you can achieve without compromising on safety or the environment. This will need early and thorough engagement with land-owners to identify constraints, requirements and options. Selecting the best access options will rely on a deep understanding of the biodiversity and heritage values of the site through desktop analysis combined with intensive field observations and data collection.

We selected access routes using a variety of considerations, including what equipment would be required on site, the duration of investigations, the significance of data we gained in the planning stage, analysis of the costs and benefits of options, consideration of the longer term benefits to the land-owners, and consideration of future works.

Ultimately we used a combination of access methods including foot tracks, temporary and permanent roads, and helicopter access. Again, it was crucial that we chose the right contractors who could cope with the conditions and understand the constraints. Our excellent local contractors were integral to our success.

Environment

Conducting works in a region of high natural values demands deep consideration of strategies to avoid or reduce long-term impacts and of what remediation efforts will be necessary and effective.

In one particular instance, we identified and implemented a range of strategies to create a 1.2 km foot-access track in a very sensitive and damp area that was likely to become muddy and highly degraded under the pressure of constant foot traffic during the duration of the works. To protect against this, we hand-cleared the site, developed suitable drainage channels, stabilised the banks, then deployed geo-fabric matting onto which we laid a top coat of clean and approved local woodchips. This innovative solution proved highly successful: it provided solid, safe and reliable footing, excellent drainage and made clearing up the site relatively easy and efficient as the woodchips could be wrapped in the geo-fabric matting, bagged and removed from the site. Once the works were completed, the cut-back vegetation was relatively unscathed, and was able to re-shoot and re-establish rapidly.

Stakeholder and community engagement

Continuous and inclusive community and stakeholder engagement, tailored to the particular community or stakeholder segment, is critical for the success of any project – and the earlier it begins, the better. In our project, we went out on the front foot, building a shared understanding of our objectives, making detailed information available and inviting stakeholders to raise any concerns with our team. We even facilitated site visits for key stakeholders to gain a fuller understanding of the works and build trust.

Many project proponents will tell stakeholders and communities that they want them ‘to come on the journey’ – but we walked the talk, inviting stakeholders to check our milestones, come along to inspect aspects of the work, and to share their feedback.

Cultural heritage

Over a sustained period, Hydro Tasmania has undertaken intensive desktop and field analysis of particular regions and their history. In addition to this rich database of information, Entura has access to specialist cultural heritage consultants who document heritage sites and support us to manage these sites in accordance within the appropriate legislation requirements. Early notification and thorough assessment early in the planning phase indicates whether a heritage site or specific location is likely to be encountered, which enables processes to be established to mitigate heritage risk, minimise site damage and, in some instances, plan for total avoidance and re-siting of works.

In our project, the early engagement of reputable consultants gave us confidence that any areas of significance had been identified. We clearly defined these areas of significance and protected them from any impacts from the works.

Water supply

Drilling investigations require a significant volume of water every day. But not all, if any, remote locations have a ready supply, and if so it’s usually some distance away. Geotech drilling investigations require up to 30,000L/day depending on ground conditions, so the ability to capture and re-circulate water and reduce sediment discharge to the natural environment is crucial in remote locations. Sometimes this needs a bit of innovative thinking to achieve.

Working in a naturally wet environment and on a hillside enabled us to trap natural run-off and control flow to a small header tank (44 gallon drum), then pipe the water to 3 x 10,000L tanks at a flow rate over 24hr period. Three sandbags, float switches and low-impact plastic irrigation pipe allowed us to supply the drill rig with water for 90% of its operation, only having to stop temporarily while drilling during a 5-day period without rainfall.

The creation of a small pond on a steep downhill slope minimised environmental impact downstream and allowed a steady flow of water to continue over the micro dam. The header tank minimised air locks, while tank float switches prevented overflow on the drill site.

By capturing water above the work site, we eliminated the need for extra foot tracks to the creek down in the valley or the need to pump and re-fuel a diesel water pump or to truck water in over 2 km.

Climate conditions

Projects sometimes can’t wait for the perfect time of year to commence. In Tasmania, this brings the challenges of adverse weather conditions and extreme events such as snow and bushfire – even within the same month!

Our remote projects faced these challenges, including frozen water pipes, snowed-in access routes and the risk of bushfire. Planning, watching the weather, and evacuation plans became a daily function.

At one particular location we soon learned that water freezing overnight in pipes could cause significant delays in the morning. Our quick solution was to drain the pipes at night to avoid the problem reoccurring.