‘Dams for People, Water, Environment and Development’ – some reflections from ICOLD 2024

Entura’s Amanda Ashworth (Managing Director) and Richard Herweynen (Technical Director, Water) recently attended the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD) 2024 Annual Meeting and International Symposium, held in New Delhi. Amanda presented on building dam safety capability, skills and competencies, while Richard presented on Hydro Tasmania’s risk-based, systems approach to dam safety management, and the importance of pumped hydro in Australia’s energy transition.

Here they share some reflections on ICOLD 2024 …

Richard Herweynen – on the value of storage, ‘right dams’, and stewardship

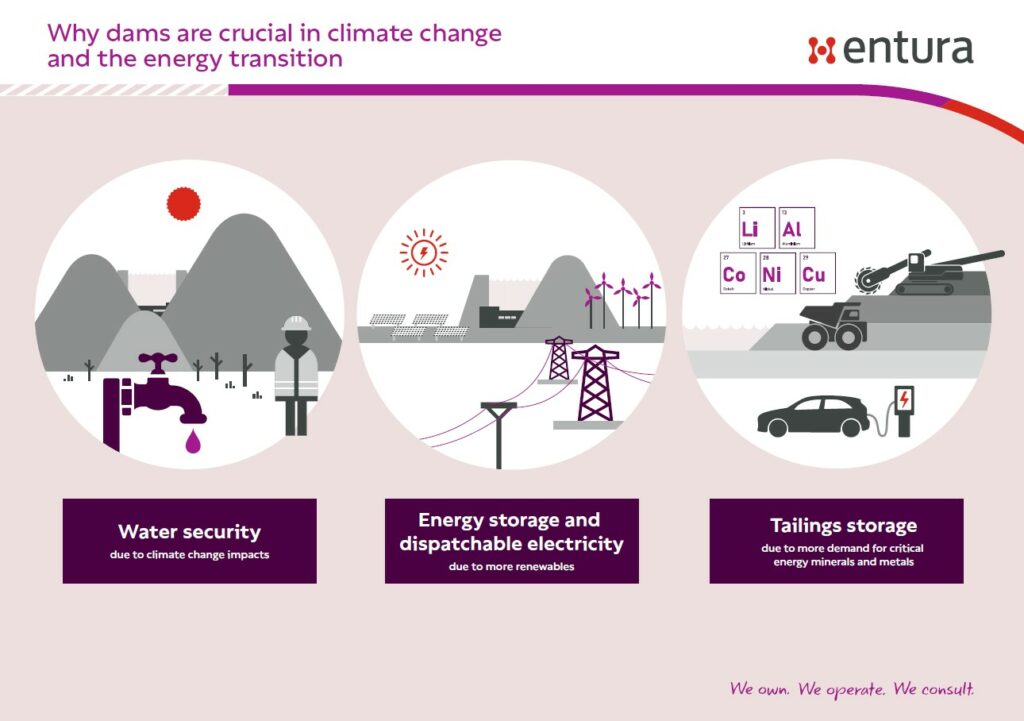

At ICOLD 2024 we were reminded again that water storages will be critical for the world’s ability to deal with climate change and meet the growing global population’s needs for food and water. We can expect greater climate variability and therefore more variability in river flows, which means that more storage will be needed to ensure a high level of reliability of water supply. Without more water storages to buffer climate impacts, heavily water-dependent sectors like agriculture will be impacted.

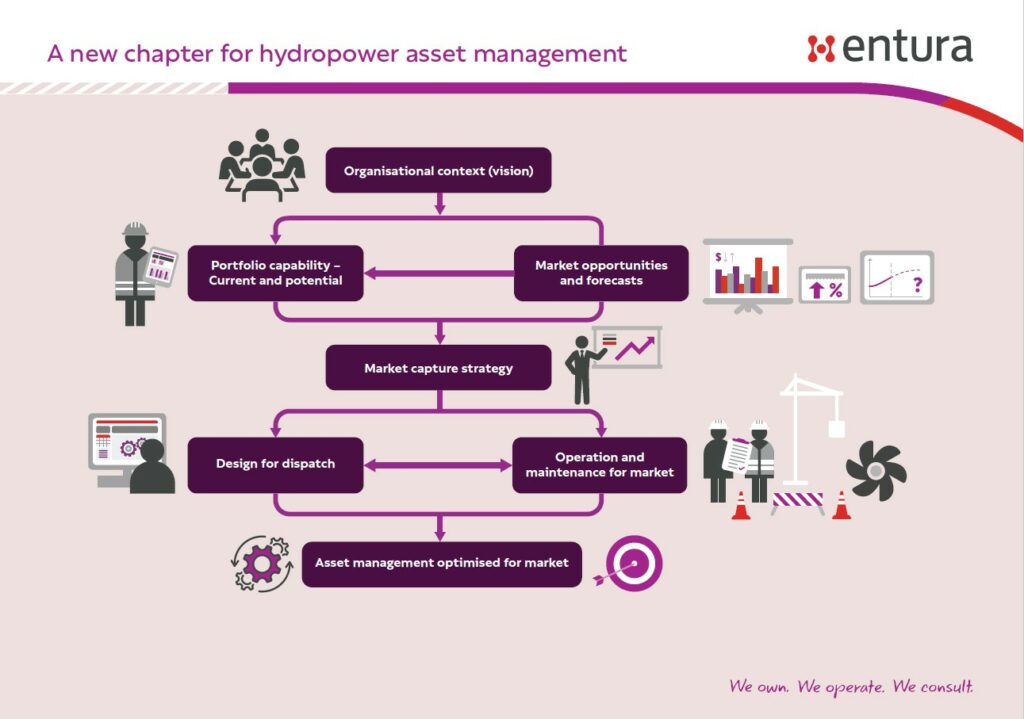

To slow the rate of climate change, we must decarbonise our economies – but without significant energy storage, it will be difficult to transition from thermal power to variable renewable energy (wind and solar). Pablo Valverde, representing the International Hydropower Association (IHA), said at the conference that ‘storage is the hidden crisis within the crisis’. There was a lot of discussion at ICOLD 2024 about pumped hydro energy storage as a promising part of the solution. It is also important, however, to remember that conventional hydropower, with significant water storage, can be repurposed operationally to provide a firming role too. Water storage is the biggest ‘battery’ of the world and will be a critical element in the energy transition.

With the title of the ICOLD Symposium being ‘Dams for People, Water, Environment and Development’, I reflected again on the need for ‘right dams’ rather than ‘no dams’. ‘Right dams’ are those that achieve a balance among people, water, environment and development. In the opening address, we were reminded of the links between ‘ecology’ and ‘economy’ – which are not only connected by their linguistic roots but also by the dependence of any successful economy on the natural environment. It is our ethical responsibility to manage the environment with care.

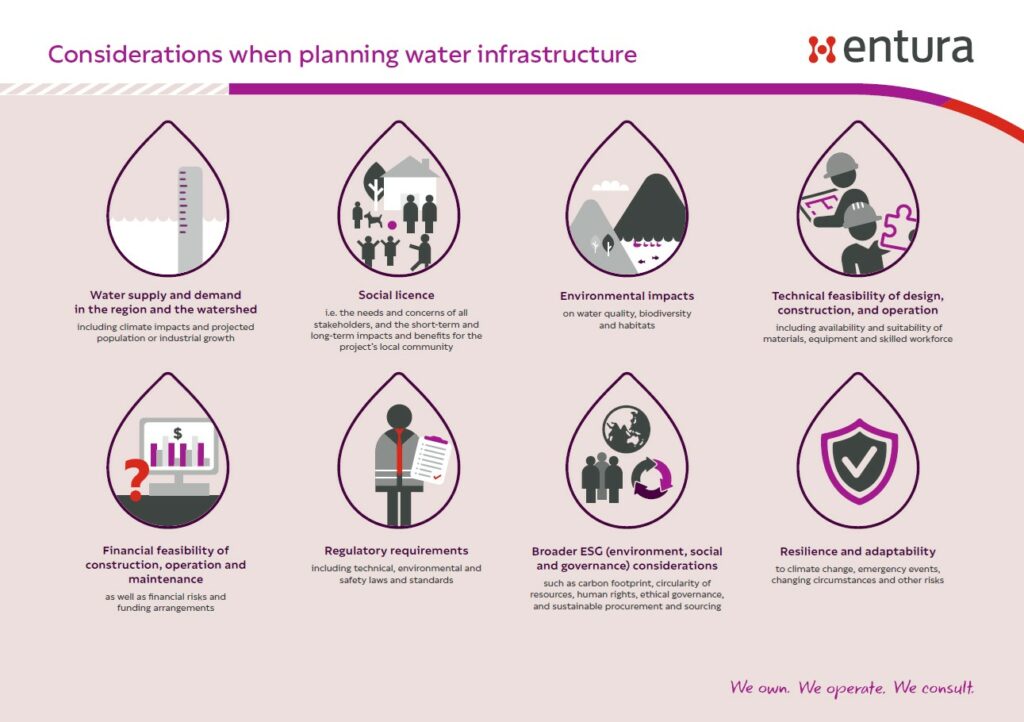

When planning and designing water storages, we must recognise that a river provides ecological services and that affected people should be engaged and involved in achieving the right balance. If appropriate project sites are selected and designs strive to mitigate impacts, it is possible for a dam project’s positive contribution to be greater than its environmental impact, as was showcased in number of projects presented at the ICOLD gathering. Finding the balance is our challenge as dam engineers.

The president of ICOLD, Michel Lino, reminded delegates that the safety of dams has always been ICOLD’s focus, and that there is more to be done to improve dam safety around the world. At one session, Piotr Sliwinski discussed the Topola Dam in Poland, which failed during recent floods due to overtopping of the emergency spillway. Sharing and learning together from such experiences is an important benefit of participating in the ICOLD community.

Alejandro Pujol from Argentina, who chaired one of the ‘Dam Safety Management and Engineering’ sessions, reflected that in ICOLD’s early years the focus was on better ways to design and construct new dams, but the spotlight has now shifted to the long-term health of existing dams. It is critical that dams remain safe throughout the challenges that nature delivers, from floods to earthquakes. In reality, dams usually continue to operate long beyond their 80–100 year design life if they are structurally safe, as evidenced in the examples of long-lived dams presented by Martin Wieland from Switzerland. He suggested that the lifespan of well-designed, well-constructed, well-maintained and well-operated dams can even exceed 200 years. As dam engineers, no matter the part we play in the life of a dam, we have a responsibility to do it well.

From my conversations with a number of dam engineers representing the ICOLD Young Professional Forum (YPF), and seeing the progress of this body within the ICOLD community, I believe that the dam industry is in good hands – although, of course, there is always more to be done. I was pleased to see an Australian, Brandon Pearce, voted onto the ICOLD YPF Board.

Another YPF member, Sam Tudor from the UK, reminded us in his address of the importance of knowledge transfer, the moral obligation we all have especially to the downstream communities of our dams, and our stewardship role. He was referencing his experience of looking after dams that are more than 120 years old – all built long before he was born. Many of our colleagues across Entura and Hydro Tasmania feel this same sense of responsibility and pride when we work on Hydro Tasmania’s assets, which were built over more than a century and have been fundamental to shaping our state’s economy and delivering the quality of life we now enjoy. It is up to all of us to carry the positive legacy of these assets forward with care and custodianship, for the benefit of future generations.

Amanda Ashworth – on costs and benefits, dam safety, and an inclusive workforce

Like Richard, I found much food for thought at ICOLD 2024. For me, it reinforced the need to accelerate hydropower globally, particularly in places where the total resource is as yet underdeveloped. To do so, we will need regulatory frameworks that support success – such as by monetising storage and recognising it as an official use – and administrative reforms that ease the challenges of achieving planning approvals, grid connection agreements and financing for long-duration storage. We must encourage research and development to move our sector forward: from multi-energy hybrids to advanced construction materials and innovations to improve rehabilitation.

In particular, I’ve been reflecting on how our sector could extend our thinking and discourse about the impacts and benefits equation beyond the broad answer that dams are good for the net zero transition. How can we enact and communicate the many other potential local environmental and social benefits and long-term value from dams?

Much of the world’s existing critical infrastructure came at a significant financial expense as well as social and environmental costs – so it is our obligation to pay back that investment by maximising every dam’s effective life. When we invest in extending the lifespan of dam infrastructure through effective asset management and maintenance, and when we maximise generation or the value of storage in the market, we increase the ‘return on investment’ against the financial, social and environmental impacts incurred in the past.

Of course, the global dams community must continue to prioritise dam safety and work towards a ‘safety culture’. I was pleased to hear Debashree Mukherjee, Secretary of the Ministry of Jal Shakti, celebrate the progress on finalising regulations across states to enact India’s Federal Dam Safety Act and establishing two centres of excellence to lift capacity across the nation. Dam safety depends on well-trained people with the right skills and competencies to comply with evolving standards, apply new technologies, and respond effectively to changing operational circumstances and demands.

I also enjoyed hearing from ICOLD’s gender and diversity committee on its progress, including updates from around 14 nations on their efforts to build a more inclusive renewable energy and dams workforce. This is front of mind for us, as we step up Entura’s own focus and actions on gender equity throughout our business this year.

The challenges facing our dams community – and our planet – are enormous, but there is certainly much to be excited about, and we look forward to continuing these important conversations over the next year.

From Richard, Amanda and Entura’s team, many thanks to the Indian National Committee on Large Dams (INCOLD) for organising and hosting this year’s ICOLD event, supporting our sector to build international professional networks, and facilitating the sharing of experiences and knowledge across the globe – all of which are so important for growing the ‘ICOLD family’ and supporting a safer, more resilient and more sustainable water and energy future.

Growing the future of hydropower – observations from a career in the industry

Entura’s Senior Principal Hydropower, Flavio Campos, knows hydropower inside out. Flavio has recently joined Entura, after working around the world on significant hydropower projects ranging from 30 MW to a whopping 8,240 MW. We asked him to share some of his hydropower journey, what excites him about the future of the sector, and what’s different about conventional hydropower and pumped hydro in supporting the clean energy transition …

When I immigrated from Brazil to Canada in 2012, it was no accident that I settled in Ontario, near Niagara Falls. I had taken a job with a consulting firm that had a hydropower hub strategically located in the Niagara region due to its long history of hydropower.

The Niagara region is the home of the Adams Power Plant, completed in 1886 – the first alternating current (AC) power plant built at scale, delivering an installed capacity of 37 MW at 2,200 V. The voltage is stepped up by a transformer to 11,000 V, allowing for an economic transmission line reaching to the city of Buffalo, NY, 32 km away. The concept was launched by engineer Nikola Tesla in collaboration with George Westinghouse, beating Thomas Edison’s bid, which was based on a direct current (DC) system. Tesla’s dream of harnessing the awesome power of Niagara Falls was realised by the end of the 19th century, when hundreds of small hydropower plants emerged and multiple forms of electricity utilisation spread across the world.

The hydropower boom, led by Brazil and China

When I started my career in the hydropower industry in 1995, I could feel the ongoing impact of the great hydropower boom that was led by Brazil and China through the 1970s and 1980s. In 1999, I was construction manager for Tucurui Dam, one of the biggest hydropower plants in Brazil and the world at that time (now ranked 8th in the world), delivering a total installed capacity of 8,240 MW. As part of my role, in order to raise production to the expected rates, I was able to visit China’s Three Gorges Dam during construction and learn about their techniques and massive concrete operations.

In the 1990s, Brazil’s hydropower industry had plenty of experienced professionals, from construction trading foremen and general superintendents to highly educated engineering professionals from whom I had the privilege to learn.

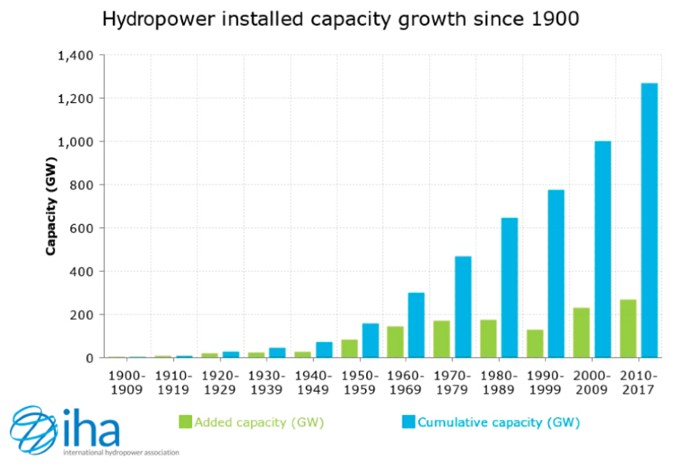

Since those glorious decades, global hydropower capacity has increased significantly. The strongest period was 2007 to 2016, when more than 30 GW was added per year on average. Since 2017, the industry has slumped to only 22 GW per year on average, with only 13.7 GW installed in 2023. However, it is interesting that of the new 13.7 GW, 6.5 GW was delivered as pumped hydro energy storage.

A new wave of pumped hydro

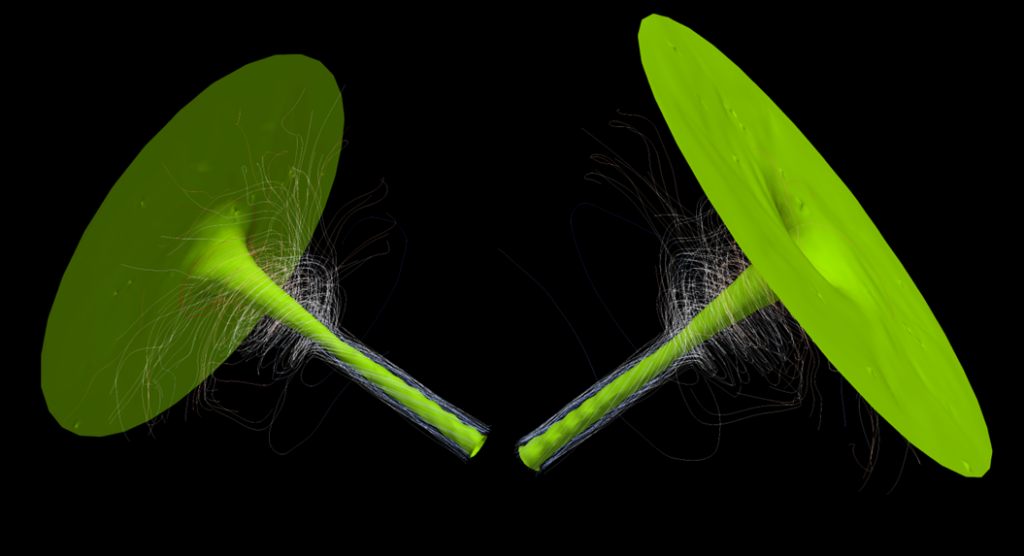

At a HydroVision International conference in Portland, Oregon, in 2019, I noticed that pumped hydro was a significant topic of discussion. The conference highlighted several factors making pumped hydro projects attractive for the clean energy transition: the ‘battery’ feature itself which helps to balance supply and demand, its contributions to grid stability, its lower environmental impact compared to conventional hydropower, the availability and efficiency of variable-speed units, and the cost comparison against other types of batteries.

Projections of a new wave of pumped storage soon evolved from conference coffee-break chatter to reality: in 2022, more than 10 GW of pumped hydro was delivered, the most ever achieved by the industry. Most of this has been delivered in China, where top-down policies imposed by government can deliver rapid results. Other countries operating on a more open-market basis need to improve the mechanisms to foster pumped hydro so that it can support the grid effectively as other variable renewable energy (VRE) sources, such as wind and solar, proliferate.

There is now consensus that pumped hydro is a necessity for grids to cope with increasing amounts of VRE– and the need is urgent. Pumped hydro, however, requires significant upfront investment in civil works and time to implement. Studies by the IHA indicate that besides the inherent need for additional pumped storage in the grid, the world’s conventional (non-pumped) hydropower installed capacity must double by 2050 in order to achieve net-zero transition targets. This will be challenging, given such a low level of new hydropower worldwide in recent years, and the fact that the most attractive sites have been already developed.

There is also opportunity to re-imagine existing conventional hydropower plants to make the most of their natural battery and firming potential – by operating flexibly to support firming VRE rather than generating for maximum volume. Even where there is no market mechanism to specifically monetise this value, it could be rewarded for national or regional outcomes.

How can we achieve the much-needed growth in conventional hydro and pumped hydro?

Conventional (non-pumped) hydropower has long been recognised for clean energy and the long life of the infrastructure. The challenge now is to identify, gain approvals and sustainably deliver new projects in a world where human occupation is growing fast and reaching into the most remote corners of watersheds. Governments and regulators must assess cost benefits against the social and environmental impacts before giving the green light to new hydropower projects.

Developing pumped hydro can be more flexible, especially when it is a closed-loop system that doesn’t depend on water flows, except for first-time filling and for topping up the losses caused by evaporation. Pumped hydro is not new – in fact, it has existed for more than a century. What is new, however, is the challenge of fostering pumped hydro development at the rate needed.

The IHA has helped clarify what is needed for the industry to develop pumped hydro faster. The IHA’s Guidance Note delivers recommendations to reduce risks and enhance certainty, supporting market players to better understand the issues.

Another interesting initiative in the hydropower journey is XFLEX Hydro, a European initiative which brought together 19 entities such as IHA, EDP, EDF, Alpiq, Bechtel and others, with the objective of increasing hydropower capabilities and flexibility to cope with changing grid profiles. X-Flex has launched 7 pilot projects already – and 4 of these are pumped hydro. This combined initiative has illustrated two important areas of focus that can benefit market players and accelerate uptake:

- The need for a supportive regulatory regime: Policy-makers and other stakeholders need to facilitate the development of regulations or market mechanisms that fairly compensate pumped hydro, as well as conventional hydropower, such as ‘price cap and floor’ mechanisms, compensation for stability features provided by hydropower, and expediting the approval process while ensuring that social and environmental impacts are minimised and mitigated.

- The advantages of evolving technologies, including:

- variable-speed units, increasing flexibility

- hydraulic short-circuit operation, in which the plant can pump and generate simultaneously

- hydro/battery hybrid system, in which the battery works along with hydropower and enhances plant flexibility

- digital/AI control platforms, which can improve the overall grid efficiency and reduce downtime.

Hydropower for a better future

The challenges of rapidly building out new conventional hydropower and pumped hydro are huge. Yet, where there is a will, there is a way. Those of us who understand and believe in the benefits of conventional hydropower and pumped hydro have a duty to bring communities along on the journey and to help build a better future for the next generations.

We look forward to bringing you more of Flavio’s insights into conventional hydropower and pumped hydro in future articles. Flavio is currently contributing to a number of Entura’s assignments including supervising construction on the Genex Kidston PHES project in Queensland, for which Entura is the Owner’s Engineer, and being a key adviser on the Tarraleah upgrade as part of Hydro Tasmania’s Battery of the Nation program.

Understanding the business risks of small dams and weirs

Small dams may pose significant business risks that are often under-appreciated, even if these dams don’t pose a safety risk to the community. Managing risk is a key part of running any sustainable business and understanding how to mitigate risks requires that they are properly identified, analysed and evaluated.

The Guidelines on Risk Assessment prepared by ANCOLD (Australian National Committee on Large Dams) provides a detailed process for quantitative analysis of dam safety risks for large high-consequence dams, but adopting this process for small dams and weirs can be costly and may not be clearly justifiable.

For owners of small dams, ANCOLD has a number of other guidelines that can be useful for managing these dams, including Guidelines on the Consequence Categories for Dams and Guidelines on Dam Safety Management. Assigning a consequence category for a small dam can be a useful first step in understanding the risks – and will consider the impacts on community safety, on the environment, on the dam owner’s business, and on other social factors including impacts on health, community and business dislocation, loss of employment and damage to recreational facilities and heritage.

The consequence categories are graded from ‘Low’ to ‘Extreme’. These categories are used for a number of purposes including:

- regulatory requirements (depending on which state the dam is in)

- recommended surveillance and monitoring activities

- maintenance and operational requirements

- spillway flood capacity

- dam design standards.

The focus of ANCOLD’s consequence category guidelines is on wider community safety and impacts, but not on the dam owner’s business. This potentially leaves the dam owner exposed to significant unidentified business risks. Ideally, these should be managed consistently alongside all the other business risks.

A structured approach to assessing the business risks of small dams

ANCOLD’s Guidelines on Risk Assessment is a useful starting point for undertaking a business-focused risk assessment of small dam assets. As with all risk assessments, it is useful to follow a structured approach, including the following steps:

- identify the hazards

- brainstorm the failure modes

- estimate the likelihood of the failure

- estimate the consequences of failure

- evaluate the risks

- develop risk mitigation measures.

Such a risk assessment approach is ideally completed with a dam engineer working closely with the business owner to capture both the dam engineering and the business-specific knowledge.

1. Hazards

Dams need to be properly designed, constructed and maintained to continue to perform their function safely. It is essential to avoid becoming complacent. Floods are a significant hazard to all dams and cause around 50% of all failures in large, well-engineered embankment dams. Small dams are often constructed with no or minimal engineering input into the design or construction and as a result may have inherent defects that may not manifest themselves until years later.

Dams in general do not require a lot of maintenance; however, a lack of suitable maintenance can lead to failures. A key maintenance activity is management of vegetation so that trees do not establish themselves in the embankment. Tree roots can create leakage paths that could lead to piping or internal erosion, and ultimately to a failure.

2. Failure modes

A key part of the expertise of a dams engineer is understanding how different types of dams can fail, which is crucial for identifying potential failure modes. The ANCOLD guidelines on risk assessment recommend completing a site inspection of the dam to help identify the key ways in which the dam could fail. The inspection should be conducted with the dam owner to look for evidence of failure modes, such as:

- deformation or cracking, which may indicate issues with the stability of the dam

- wet areas or flows through the dam, which may indicate a piping failure

- spillways where the original crest is filled in or raised to increase storage in the reservoir, which can often be an area of concern

- erosion close to the dam from operation of the spillway, which could lead to undermining and instability of the dam wall.

Typically, failure modes are identified in a workshop setting and then prioritised by criticality. The full list of failure modes is then reduced to a shortlist of those that are most critical.

3. Likelihood of failure

ANCOLD’s Guidelines on Risk Assessment provides an approach that can be used for detailed quantitative risk assessments; however, such approaches require significant effort to apply and can be costly. For small dams, it can be more appropriate to use a risk matrix approach, similar to that outlined in the Australian standard AS ISO 31000 Risk Management.

Typically, most businesses have a standard risk assessment procedure that can be adapted to give a qualitative or semi-qualitative assessment of likelihood. An experienced dams engineer will be able to assign a likelihood for each of the credible failure modes based on engineering judgement and some simple calculations (e.g. using regional flood estimates and estimates of the spillway discharge capacity). Failure modes for dams that are well designed and constructed will often have a likelihood rating of ‘Rare’ or ‘Unlikely’. The likelihood may be higher for dams in poor condition or with identified deficiencies.

4. Consequences of failure

A business risk assessment focuses on the consequences to the business, rather than the wider community, if the small dam were to fail. This will be unique to each business and will need input from the owner. It can be assessed by working through a series of questions about the need for the dam and its purpose – for example:

- What is the water in the dam used for? Can the business function without the water or the storage space in the dam?

- Are there alternative sources for the water that can be quickly accessed, and will these be sufficient for normal operations or would it be necessary to reduce operation?

- Is there business infrastructure downstream of the dam, and could a failure of the dam cause failure of these assets (e.g. pumping stations, water treatment plants or other dams) that would impact business operations? Can the business operate without these assets?

- How will customers be affected and what are the reputational consequences of not being able to supply or only partially supply?

- What are the financial implications for the business, and is there insurance that would cover the cost of the event, including consequential losses?

- How long would it take to replace the dam (including refilling) and the other assets?

5. Evaluation of risks

Using the business’s standard risk assessment tool enables comparison of the small dam risks against other business risks on a consistent basis (e.g. safety risks to employees). The level of risk will indicate the urgency of addressing the risk. This process allows a clearly articulated justification to be presented to the business for putting in place any required mitigations. It also enables the owner to focus on the key business risks rather than become distracted by issues with lower risk.

6. Risk mitigation

Mitigations can address either likelihood or consequences and will need to be tailored to the specific risks and the business needs. Addressing the risks by reducing the likelihood will typically involve physical works to the dam – for example, increasing the size of the spillway to reduce the likelihood of an overtopping failure, or managing vegetation to reduce the likelihood of a piping failure.

Where reducing the likelihood is not practical or not sufficient, addressing the consequences may be an effective approach. Addressing the consequences may involve options such as securing alternative water supplies, contingency planning to reduce impacts on customers, or insurance to cover the financial losses.

Bringing it all together for better business insights

Entura has undertaken qualitative and semi-qualitative small dam risk assessments for a number of clients in a cooperative environment to bring together our dams engineering expertise with the owner’s knowledge of their business. This is a cost-effective approach that has provided clarity on the specific business risks related to small dams, allowing targeted risk mitigation measures to be put in place. The process has provided important insights enabling owners to justify business decisions and reduce their overall business risk exposure.

If you have small dams and would like to talk with us about assessing your business risks, contact Phillip Ellerton or Richard Herweynen.

About the author

Paul Southcott is Entura’s Senior Principal – Dams and Headworks. Paul has an outstanding depth of knowledge and skill developed over more than 3 decades in the fields of civil and dam engineering. He is a highly respected dams specialist and was recognised as Tasmania’s Professional Engineer of the Year in Engineers Australia’s 2021 Engineering Excellence Awards. Paul has contributed to many major dam and hydropower projects in Australia and abroad, including Tasmania’s ‘Battery of the Nation’, the Tarraleah hydropower scheme, Snowy Hydro, and numerous programs of work for water utilities including SeqWater, Sun Water and SAWater. His expertise is a crucial part of Entura’s ongoing support for upgrade and safety works for Hydro Tasmania’s and TasWater’s extensive dams portfolios. Paul is passionate about furthering the engineering profession through knowledge sharing, and has supported many young and emerging engineers through training and mentoring.

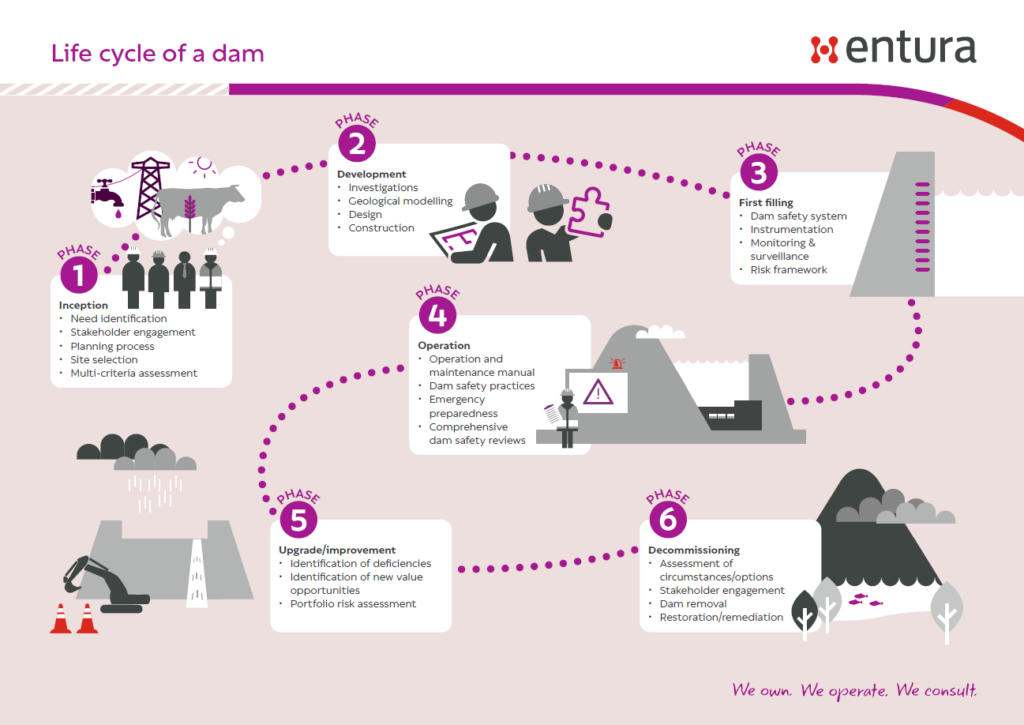

The life cycle of a dam – Bringing it all together

Dams, like all of us, go through several life stages. Some dams have harder lives. Some age more quickly. Some need a lot of attention, and some are more robust. Let’s talk a bit about a dam’s life – and revisit some of our previous articles on dam engineering.

Phase 1: Inception

The starting point of the dam life cycle is the planning process – where a need is identified and it is determined that the way to meet that need is to create a water storage by constructing a dam. It is essential that this planning process involves effective stakeholder engagement. Although there may be a primary purpose for the dam, it is very common through the stakeholder engagement process to consider other benefits that the dam could provide, making it a multipurpose dam.

The planning process will lead to the site selection stage. Choosing a suitable site which is both technically sound and environmentally and socially acceptable will have a significant impact on the remaining stages of the dam’s life. Multi-criteria assessment can help get the selection right, ensuring technical, financial, environmental and social aspects are considered in a balanced way.

Read our articles:

- ‘No dams’ or ‘right dams’? That is the question

- Make better decisions about hydropower and dam project options using risk-based multi-criteria assessment

Phase 2: Development

The development phase includes the investigation, design and construction of the dam. Every dam site is different, and it is important to understand this. As a result, the ideal dam type for one location will not be the same as for another location.

Read our article:

It is important that the risks associated with the dam site are known and understood. A key risk is the geological aspects of the dam’s foundation. Are there defects that could impact the stability of the dam? Are the foundations erodible? Could permeability be an issue? A staged investigation program formulated around the geological model will help to provide this understanding.

Read our article:

Design must be in accordance with current practice, guided by engineering standards and guidelines such as ANCOLD guidelines and ICOLD bulletins. Construction needs to be in accordance with the design and should be conducted using an appropriate quality assurance system and quality control program. An Independent Technical Review Panel (ITRP) helps avoid anything falling through the cracks. (The Queensland Dam Safety Management Guideline provides some guidance about this.) An ITRP will provide strong technical governance during design and construction, utilising the collective knowledge and experience of its members.

Read our article:

Phase 3: First filling

The next phase of the dam’s life is the first filling. This is a very exciting time, but it is also known to be the highest risk stage of a dam’s life. As a result, we need to be prepared. A dam safety system needs to be in place, along with the necessary instrumentation to monitor the dam during this first fill.

Read our article:

In case of any incident occurring during first filling, it’s crucial that the dam safety emergency plan has been prepared and the dam safety manager identified. As the dam fills, there should be a heightened level of monitoring and surveillance, using this information to compare the actual performance against what was expected.

Entura has used a risk framework to determine a dam’s readiness to impound, such as for Murum Dam in Malaysia. Of course, some reservoirs take a long time to fill, potentially over a number of years, so this heightened level of monitoring and surveillance could go on for some time. There could also be saddle dams that experience water against them much later than the main dam.

Phase 4: Operation

Now begins what, hopefully, will be a long phase of normal operation. The dam will have an operation and maintenance manual to ensure that the dam is operated as intended and regular routines occur. Good dam safety practices must continue throughout the operational life, including dam surveillance, routine inspections, and ongoing emergency preparedness should any dam safety incidents, major floods or seismic events occur. Emergency plans should be tested regularly to ensure they are appropriate and robust.

Read our articles:

- What can dam owners do to better manage floods and avoid the blame game?

- How robust is your emergency preparedness?

During the operational phase of a dam, it is also important that comprehensive dam safety reviews (DSRs) occur every 20 years, or whenever there has been a major event or a change in standards or guidelines. The intent of a DSR is to determine the safety of the dam against current practice and the current condition of the dam. It’s important that the DSR considers the potential failure modes for the dam.

To undertake a DSR, good historical documentation for the dam will be needed. If the records aren’t great, or there are significant gaps, the DSR may require additional investigations and analysis to be undertaken.

Read our article:

In addition, it is critical that the public is kept safe around dams and throughout the operation of dams. In 2012 ICOLD established a working committee to identify these public safety risks, describe the international state of practice to manage and mitigate the risks, and develop a guidance bulletin on best-practice measures and public education about safety around dams.

Read our article:

Phase 5: Upgrade and improvement

If the DSR identifies deficiencies in the dam, a dam safety upgrade may be needed. This is the next stage of a dam’s life. A risk framework can often be used to justify and guide these upgrades.

Read our article:

Dam upgrades may not always be due to a dam safety issue; they may also be driven by the opportunity to increase value, which may be able to be achieved through measures such as raising the height of the dam. They can also be driven by changing design standards, changes to legislation, greater understanding about extreme hazards, or (more recently) climate change impacts.

Read our article:

With a large portfolio of dams, the demand on resources (both capital and human) can be significant. A portfolio risk assessment (PRA) allows owners of dams and other water assets to see the bigger picture of how to prioritise their efforts and resources to achieve the best safety results across the whole portfolio.

Read our articles:

- Portfolio risk assessment takes dam safety programs to the next level

- Safer dams are a matter of priority

Phase 6: Decommissioning

This final phase of a dam’s life may actually never occur, as most dams continue to provide a valuable service to society indefinitely. But, with time, the needs of the community may change, or the commercial benefits of the dam may reduce. In these circumstances, the dam may be decommissioned and removed. This decision is not likely to be made quickly, and for good reason, as this is a very complex matter involving many stakeholders. A recent example is the landmark decision to remove 4 dams along the Klamath River in northern California and southern Oregon. This is the most extensive dam removal and river restoration project in US history.

Although some dams may at some stage be decommissioned and removed, more dams will always be needed to meet the world’s needs for water security, clean energy, and storage of mining tailings.

Read our article:

And so the life cycle begins, all over again.

(more…)From binoculars and boots to bytes and bots: harnessing remote sensing and AI for ecological monitoring

For power and water developments to be truly sustainable, we must preserve and protect biodiversity. But it can be difficult to look after what you don’t know about or don’t understand. In the age of Big Data, automation, AI and increasingly clever gadgets, field ecologists can now do more with less – in other words, get lots of good information very quickly and with far less cost. That’s good for projects and for our planet.

Field ecologists spend much of our time gathering information on species occurrence, distribution, abundance, habitat requirements, and threats. We need methods to detect and quantify biodiversity that are efficient and sensitive, and not biased, invasive or destructive.

Our job increasingly involves leveraging the advances in monitoring technology, computing power, and machine-learning methods to help our clients assess, avoid, mitigate or offset environmental impacts. Vast amounts of visual, spatial, genetic and acoustic information can now be captured using new tools such as ‘camera traps’, automated image classifiers, passive acoustic monitoring, automated species detection from audio data, and eDNA.

Camera trapping

Camera trap monitoring (using digital cameras activated by motion or heat) is a powerful tool for observing and cataloguing species, but it can generate enormous numbers of images. Each image needs to be viewed and tagged to create meaningful data. Until now, that’s taken up a lot of human time. Now, however, machine-learning models can automate the process of detecting and classifying animals.

For example, the ‘MegaDetector’ is an open-source image-segmentation tool from Google that can automatically place a bounding box around a region of interest in the environment, in this case zooming in on an animal and isolating it from the background. This can be put into a wildlife-species classifier before verification by a human, raising the accuracy of classifying some species to up to 99% and increasing the speed at least 20-fold – in fact, it is estimated that approximately 5,000 images can be tagged per hour using these workflows.

Examples of camera trap images with the MegaDetector bounding box applied

As well as detecting rare, cryptic and elusive native species, camera trapping can also detect and help to quantify the threat posed by introduced animals. Technology has even been developed that enables humane, automated feral cat and fox control: the ‘Felixer’ device uses rangefinder sensors to distinguish target cats and foxes from non-target wildlife and humans. Felixers can even be programmed to play a variety of audio lures to attract feral cats and foxes. The targets are detected via a camera-based AI system working in tandem with four LiDARs. These devices are operating in all Australian states and territories, protecting threatened species including bilbies, bettongs, rock wallabies, quolls, malleefowl, ground parrots, numbats and rare dunnarts and rodents.

Passive acoustic monitoring

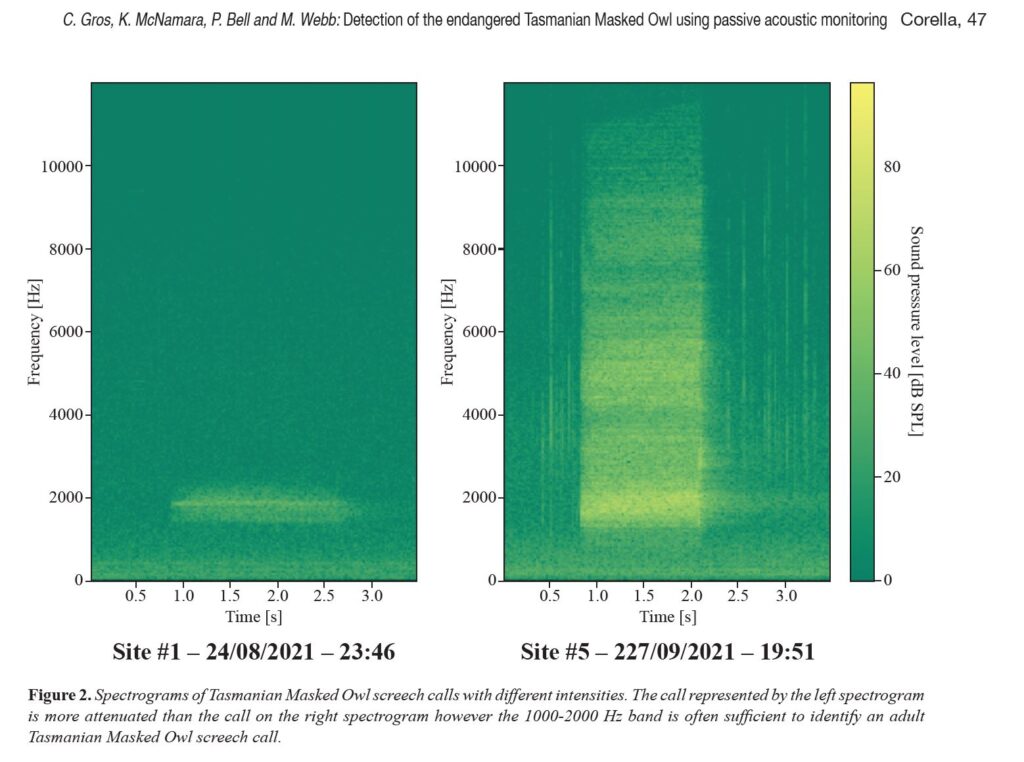

Another recent advance that is revolutionising species detection is passive acoustic monitoring. In Tasmania, the endangered, cryptic, poorly understood Tasmanian masked owl (Tyto novaehollandiae castanops) has traditionally been detected through ‘call-playback surveys’ – experts listening for owl vocalisations in response to broadcasting recorded owl calls – but some owls just won’t play the game! Passive acoustic monitoring is a more effective method for detecting these birds, with recorders deployed and set to record from dusk until dawn. Software has been developed to graph the recorded sounds as spectrograms and then automatically detect this species’ persistent screech calls and even chattering calls. Work is underway to differentiate between adult and juvenile calls, which will help identify nearby roosting and nesting sites. With robust bioacoustic recorders and partial automation of analysis, we can detect this elusive species and identify critically important nesting sites more accurately, rapidly and at less cost. The technology can also be used to detect other species with distinctive vocalisations.

Screeching calls of an adult Tasmanian masked owl can be heard in the audio above

Wildlife Acoustics Song Meter SM4 deployed by Entura ecologists in north-west Tasmania, within a patch of tall eucalypt forest assessed to be potentially suitable nesting habitat for Tasmanian masked owls

eDNA, barcoding and metabarcoding

Increasingly rapid and relatively cheap DNA sequencing techniques are also transforming biodiversity research. Environmental DNA (eDNA) is genetic material from the hair, skin, urine, faeces, gametes or carcasses of organisms that can be found in the environment. This eDNA data can be interpreted through ‘barcoding’, which uses species-specific tools to detect the DNA fragments of a single species within an environmental sample, as well as ‘metabarcoding’, which can simultaneously detect millions of DNA fragments from the widest possible range of species. eDNA barcoding is particularly useful for detecting invasive, rare and cryptic species in places that are otherwise difficult to survey.

What’s next?

Fauna survey methodologies are evolving fast. Soon we’re likely to see continuous, automated wildlife detection and species identification, with solar-powered detection units (camera traps, bioacoustic recorders, etc.) autonomously uploading data to the cloud. This could produce high-resolution activity maps that update in real time and at large scale. Systems that can compute and upload data autonomously and are self-sufficient in energy will allow us to obtain accurate and extensive information from almost anywhere, anytime.

So, are clever bots and gizmos going to take our jobs? Will we never head out into the field with our binoculars again? Not quite yet (happily!), but with increasingly robust hardware, modern computing power and machine-learning, we can do more for our clients and our planet, and that’s a great win–win for us all.

If you’d like to talk with Entura about our ecological monitoring services, contact Raymond Brereton.

About the author

Dr Carley Fuller is an Environmental Consultant at Entura. She is an ecologist with expertise in environmental impact assessments for renewable energy projects including solar, wind, hydropower, hybrid, and transmission infrastructure developments. She has a decade of experience working in multiple Australian jurisdictions and internationally in the United States, Latin America, and the Pacific as both a research scientist and consultant. Carley has a strong technical background in plant science, land-use planning, GIS and natural values assessment and completed her PhD in conservation science at the University of Tasmania. She is passionate about leveraging environmental data to provide tailored decision support for a range of stakeholders.

MORE THOUGHT LEADERSHIP ARTICLES

Understanding the challenges of medium-sized power systems

Power systems in the range of 200–500 MW face unique challenges, including how to incorporate increasing amounts of intermittent inverter-based renewable energy, such as solar PV and wind generation. What are these challenges, and how can they be solved?

Large power systems, like the interconnected grid of the eastern Australian states, are well-understood. These systems have extensive engineering support and sophisticated models to handle renewable energy integration, with network-wide inverter-based renewables (IBR) penetrations ranging from 25–50% and local penetrations up to approximately 115%. Similarly, small power systems, such as those up to 30 MW found in remote mining sites, also manage high IBR penetrations, sometimes reaching 100%.

However, power systems in the range of 200–500 MW face unique challenges. We call these systems ‘anti-Goldilocks’ power systems. Stemming from the children’s story of ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’, Goldilocks has come to mean something neither too big nor too small, neither too complex nor too simple – in other words, ‘just right’. An anti-Goldilocks system, on the contrary, has an uncomfortable combination of both large and small system challenges without the solutions available to a large system operator.

Examples of anti-Goldilocks (AG) power systems in Australia and the Pacific include:

- Fiji power system

- New Caledonia

- French Polynesia (Tahiti)

- Guam

- PNG (Port Moresby)

- Darwin Katherine interconnected power system

- North-west minerals power system (Mt Isa and surrounds)

- Western Australian north-west interconnected system

- the Tasmanian power system during low demand.

Common challenges in AG power systems

AG power systems share characteristics that make managing high IBR penetration both inevitable and challenging.

- 1. Geographical distribution and stability

In small power systems, all generation sources are often close together, ensuring good transient stability. Large systems benefit from high interconnection levels that couple machine inertias effectively. AG power systems, however, are geographically spread out without these stabilising features, leading to difficult transient stability conditions.

- 2. Environmental conditions and storage

Small systems can install enough battery energy storage (BESS) to manage fluctuations in renewable energy sources. Large systems distribute IBR across vast areas, minimising localised impacts from wind and irradiance. AG systems, however, typically have most IBR within a 100 km radius, which means that similar environmental conditions can affect all IBR at once, potentially causing sudden shortfalls in generation.

- 3. Rapid changes in IBR penetration

AG power systems often have high electricity costs and small sizes relative to each IBR station. This makes renewable generation very attractive financially, and a single IBR connection can immediately cause significant penetration increases, potentially reaching 80%+ quickly and catching network operators off guard.

- 4. Responsibility for quality and ancillary services

Because small systems typically have just one generator and one consumer, they tend to have straightforward responsibility allocation for the quality of supply and ancillary services. Large systems are either government-owned or regulated with established market mechanisms for these services. AG systems may lack these structures, often having multiple generating companies and consumers, complicating the provision and funding of necessary services.

- 5. Modelling and planning

Large systems have developed accurate models over many years. Small systems manage with less detailed models because most errors don’t significantly impact overall accuracy. AG systems typically have poor models. The requirement for greater accuracy is only a recent phenomenon, but a greater level of accuracy has been difficult to achieve due to the lack of collaboration between customers and generators, a lack of necessary modelling skills, and a reluctance to see modelling as core business.

Transitioning to inverter-based renewables: four horizons

Successful operation during the transition to IBR involves navigating 4 distinct horizons:

- H1: conventional dominance

The network is dominated by traditional plants with control based on speed and voltage droop. The system can manage almost indefinitely without wide area controls during disturbances.

- H2: high IBR penetration (60%)

There is a high level of IBR penetration, say 60%. While the distributed versus wide area control issues don’t change significantly, prolonged outages of wide area control cannot be tolerated. Systems should operate without human intervention for at least 20 minutes during such failures.

- H3: minimal rotating machines

There are periods with only one large rotating machine. Planners should ensure the system can operate for 20 minutes without human intervention if this generator fails.

- H4: full IBR operation

The system operates with 100% IBR and should be designed to manage without human intervention for 20 minutes during wide area control outages.

Solutions and optimisations

AG power systems face significant but solvable challenges as IBR connections increase. While installing sufficient battery capacity and running rotating plants at low output or adding synchronous condensers can help, these solutions can be costly. Therefore, optimising solutions to minimise additional costs is essential.

Entura has worked on most of the AG power systems listed above and we have found that batteries, while helpful, are only one part of the solution. Effective rules and regulations that allocate risks and responsibilities appropriately, along with a causer-pays mentality and prudent risk acceptance, lead to the more cost-effective technical solutions.

To discuss how Entura can help you ensure the safety of your electrical assets, contact David Wilkey or Patrick Pease.

About the author

David Wilkey is the Senior Principal, Grid & Power, at Entura. David has more than 25 years’ consulting experience across a wide range of electrical engineering projects, including power system studies, power system and generator protection, generator connection rules, and primary plant electrical engineering. David’s primary interests include all aspects of electrical engineering for hydropower projects, such as hydro turbine governors, generator excitation and generator protection systems.

MORE THOUGHT LEADERSHIP ARTICLES

Bifacial solar PV: shining light on all the angles

In the booming global solar industry, installation of bifacial panels has been rapidly overtaking conventional monofacial modules, particularly in utility-scale projects but increasingly at smaller scales (<5 MW) too. But are they the right technical investment for your solar project – and what do you need to consider?

We recommend getting to grips with the benefits, constraints and implications of bifacial modules as early in the development cycle of a project as possible. Here are some observations to get you started.

What are the advantages of bifacial solar PV?

Bifacial solar PV modules are solar panels capable of generating electric current from both sides of the panel, as opposed to monofacial panels, which generate from one side only. Sunlight can pass through a transparent top layer and be absorbed by the solar cells, while sunlight reflected off surfaces can be captured through the transparent bottom layer, increasing the overall power output and potential energy yield.

The advantages of bifacial solar modules include:

- enhanced energy yields (typically 5% and can be up to 10% when optimised at particular sites) with only minor differences in supply cost

- lower levelised cost of energy (LCOE) with greater return on investment (ROI)

- increased duration of maximised power export

- enhanced performance in diffuse light conditions, such as when it is cloudy, which can be beneficial for the stability of hybrid power systems

- greater power density achieved in space-constrained sites

- better end-of-life outcomes, as glass is more readily recyclable than plastic polymers used for the backsheet of monofacial modules

- some manufacturers also claim improved durability and longevity of panels due to double glass construction rather than the glass and polymer backsheet of monofacial modules. This is claimed to be more resistant to environmental factors such as moisture, humidity and fluctuations in temperature. It has also been anecdotally suggested that the glass backface increases protection from water ingress and resistance to corrosion.

Are there any potential downsides?

Bifacial modules typically have a front-side glass thickness of 2 mm with 2 mm on the rear side, compared to monofacial modules which have 4 mm on the front side only. This can increase susceptibility to hail damage, which may require further mitigation measures in hail-prone areas and could increase the cost of insurance.

What’s albedo and why does it matter?

The more reflective a site, the better its prospects for gaining the bifacial edge. Generally, there is a linear correlation between the ground reflectance conditions (albedo) at the site and the power gain from the backside of the bifacial panels. Albedo is also the single largest factor driving bifacial gain.

But a site’s ground conditions will change over time, so one of the most important considerations when calculating the possible benefits of deploying bifacial over monofacial solar modules is determining what the long-term average albedo is at the site. Many factors can play a part in the way the albedo is modelled – including the intended use of the site once the solar plant is built, revegetation strategies, grazing livestock, the frequency of droughts and flooding events, precipitation volume and water pooling, how green the grass is, and the colour of the earth. The highest albedo factors and bifacial gain will be in conditions such as frost or snow, with its high level of reflectance. The lowest albedo factors are achieved on surfaces such as dry asphalt or grasslands.

Is more height a good thing?

Another major factor driving bifacial power is the height of the installation. Bifacial power gain increases with installation height as a greater angle is available for reflection of direct and diffuse irradiation to the rear side of the modules. This gain is most prominent typically between the installation heights of 0.5 and 1 metre before levelling out above 2 metres. In areas prone to flooding, higher installation may also provide extra resilience to increasing weather extremes.

An important consideration here, however, is that although higher installation may increase energy yield and financial returns, there may be considerable additional capital costs and greater complexity of construction of the mounting infrastructure, particularly for longer piles.

What’s the right ground cover ratio?

When the percentage of area covered by PV modules increases, the bifacial gains decrease. If more ground is covered, more area is shaded, and there will be less reflection to the rear side of PV modules. Often there is an incentive for developers to maximise the solar DC power capacity of a given site to avoid costly additional land agreements and minimise the project footprint. However, this can result in a high ground cover ratio (GCR) which can cause shading between rows. This increase in ground shading reduces backside power and energy yield gains (although it can sometimes be mitigated by the ‘backtracking’ capability of single-axis trackers).

Recently, we have been seeing developers take a more conservative approach with this in mind, preferring a GCR below or approaching 0.30.

What about shade from the mounting structure and cables?

Increasingly, manufacturers of mounting structures are looking towards maintaining structural integrity of their equipment while also minimising shading. String cabling can also be a cause of rear shading, so they should be fixed underneath the torque tubes of single-axis trackers (SAT) or underneath the mounting structure supports to minimise any impact. We are noticing an increasing focus on consistency of construction in this regard and the inclusion of this check on installation test certificates as minor shading on one module has the cascading effects of derating the entire string of modules.

Could spikes fry the electricals?

Although asset owners are most interested in the potential for greater energy yield from bifacial modules, it is necessary to also assess the electrical maximum power point voltage and current limits caused by spikes during high irradiance events. These spikes can be caused by a range of environmental factors which may be specific to sites. These include early morning frost at low temperatures, increasing sunlight irradiance at the edge of lensing clouds (magnifying glass effect), snowfall or flooding/water pooling.

In some areas which experience high ground albedo in conjunction with technical designs for favourable backside power gain, the maximum instantaneous bifacial gain can be as much as 15 to 25% for some Australian contexts, which can impact the allowable number of modules in a string as well as the input parameters to combiner boxes, inverters and cables throughout a project.

What’s next under the sun?

Solar is an exciting sector of rapid, continuous innovation, so there will no doubt be ongoing technological evolution with new implications and applications to explore. Regardless of whether bifacial panels are right for your project at this stage, it’s worthwhile considering all the options that might work best for your site. In the transition to net zero, every solar installation has a crucial role to play. The better the yield and value that can be achieved from a solar project, so much the better for the developer, the community, our environment and the future.

If you need support to assess energy yield, design, and technical considerations for your solar project, please contact our business development managers, Patrick Pease (Australia) or Shekhar Prince (international).

About the author

Lachlan McKenna is a renewable energy engineer in Entura’s renewables development team. He works on solar, wind and BESS projects from concept and design through to operations and repowering in locations throughout Australia and the Indo-Pacific region. Prior to working for Entura, Lachlan gained experience in the commercial and industrial rooftop solar sector and European offshore wind industries.

See our previous articles on how to achieve solar success:

Changing the climate future

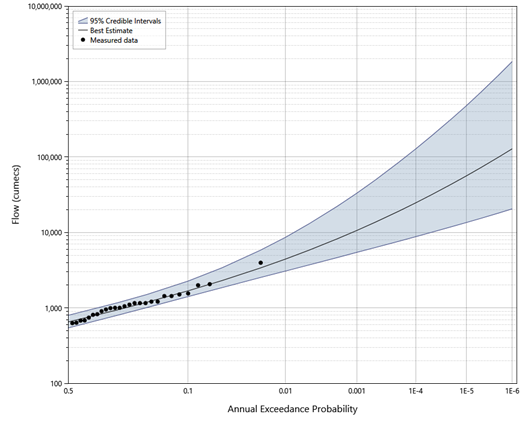

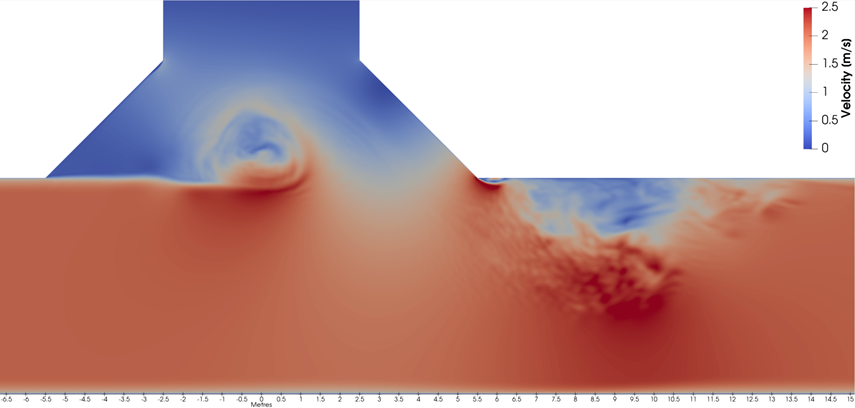

The future isn’t what it used to be. The future we now expect is one of even more intense rainfall. What can we do about it?

In Australia, there is now expected to be a 41–88 % increase in intense rainfall assuming a fossil-fuel development emission scenario by 2090, working from a 1961–90 climate base. In Tasmania, our previous vision of 2090 was an expected intense rainfall increase of only 16.3 %. So the future is looking different, with more intense rainfall. New projections are making the present and near future look different too. We now understand that there will be a 16 % increase to the current climate (2021–40) for 3-hour-duration rainstorms (since the 1961–90 period). In other words, the ‘old future’ is now and the ‘new future’ is different from what we thought.

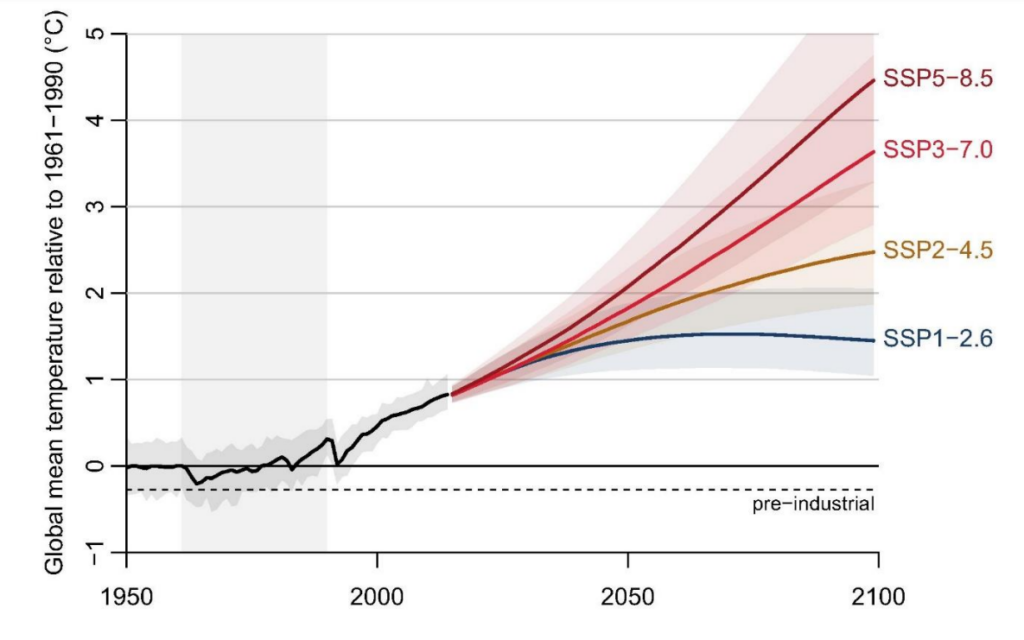

In December 2023, draft changes to the Australian Rainfall and Runoff (ARR) climate change advice were released, changing many of our projections. Between the 1961–90 rainfall data used to calculate the intensity-frequency-duration of most rainstorms and the ‘current’ climate (2021–40), there is expected to be a 1.3 °C rise in global temperature (noting that this comes on top of the already 0.3 °C increase in global temperature from the 1850–1900 pre-industrial period to 1961–90). So for a fossil-fuel development emissions scenario (SSP5–8.5, Meinshausen et al 2020), what we previously projected for intense rainfall by 2090 is now our projection for some storms in the ‘current’ climate (2021–40).

If the ‘old future’ is our new reality, what could the actual future be?

As of March 2024, the future is projected to be hotter than previously expected, and intense rainfall is expected to increase proportionally more for every degree of temperature rise. There could be a small increase in catchment losses, but these are expected to be overwhelmed by the increases in intense rainfall. There is also a better understanding of the uncertainty in the modelled projections.

An example in Tasmania

In Tasmania, water is fundamental for the environment and community, and the importance of our understanding of water is heightened by our reliance on hydropower for the bulk of our electricity. However, the climate changes discussed here are less about longer term water and energy yields than about the intense rainfall associated with flooding.

For Tasmania:

- Prior to the draft December 2023 ARR advice on climate change (Engineers Australia, 2023), with the SSP5 emission scenario with 8.5 W/m² radiative forcing there was projected to be a 16.3 % increase for all rainfall durations by 2090. The December 2023 draft advice for this scenario is that by 2090 the increase in intense rainfall is expected to be 41–88 % over the 1961–90 climate base (that is, the data you can get from the Bureau of Meteorology as the 2016 intensity-frequency-duration rainfall data). This means 41 % for 24-hour and longer duration rain storms, and up to 88 % for durations of 1 hour and shorter. These apply across Australia for rarities from an exceedance per year to the probable maximum precipitation event. There are several papers on the subject, for example Visser et al (2022) and Wasko et al (2024).

- For 1 hour and shorter duration storms, which are important for drainage from building roofs and for most town local stormwater systems, the current period (2021–40) has a 20 % increase in intense rainfall over the climate base (1961–90). This means that all designs made over the last few years using a 20 % increase in rainfall to allow for a future climate will still work as expected for the time being. But after about 2040, these designs are unlikely to perform as expected.

- For 3-hour-duration storms there is expected to be a 16 % increase over the climate base (1961–90) for the 1.3 °C rise in temperature to the ‘current’ period (2021–40). This means that what we thought would only happen in the more distant future is expected to be occurring now. The reasons we say this is ‘expected’ is that we won’t know for sure until we look back on this period with hindsight.

- For the 24 hour and longer durations, the current period (2021–40) has an 11 % increase in intense rainfall over the 1961–1990 climate base. With the non-linear relationship between rainfall and runoff, the increase in peak stream flood flow is expected to be higher than 11 % for most larger rivers, such as those that flow to our dams.

Impacts on decision-making and design

Following the Sixth Assessment Report in 2023 (AR6) by the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/), and anticipating the next one due around 2029 – and with science and engineering understanding increasing all the time – it’s likely that our projections of the future scenarios and understanding of the past will continue to evolve. Obviously, infrastructure that’s built stays built, but can be augmented. Standards and methods can’t change every year for practical reasons, but those of us impacted by climate and water are wise to remain up to date and always use the most contemporary knowledge. Asset owners, regulators, consultants and the community need to pay attention as the climate changes.

When the goal posts shift, we need to take stock of previous advice provided with old rainfall data, and consider how to include current rainfall data in new advice. As we go forward, we also need to be more careful in our language about how we reference the past, current and future.

When making decisions for infrastructure that will last at least 100 years and take 5 to 20 years to plan, design and build, such as sizing dam spillways, a range of risk mitigation strategies are required for managing an uncertain future (for example https://entura.com.au/designing-dams-for-an-uncertain-climate-future/). When reviewing the performance of existing systems, defining the ‘current climate’ is important. Climate change isn’t something just for future scenarios – we’re living it now.

Strategies to support better climate-related decision-making include:

- using the current best knowledge

- understanding data and model uncertainty

- understanding natural climate variability on seasonal to decadal time scales

- understanding that future climate scenarios are all possible

- applying sensitivity analysis

- using multi-criteria assessment

- using staging strategies

- providing options in design for changing levels of service.

If, for example, we were designing a new building to be built soon near a watercourse, all the following approaches could be considered:

- Design the level of the earthworks and finished hardstand levels to meet the level of service in the ‘current’ climate (e.g. 2021–40), considering a freeboard over the raw modelled river levels to account for uncertainty in any modelled results.

- Make allowances in the construction to address future climate scenarios (e.g. SSP5 2090) and build now only what’s prudent.

- Allow space for a future flood wall and its footings, potentially building the footings now if integrated into the current site works.

- Consider space for future flood gates on site entry, and consider their storage and other requirements that are best allowed for in the current construction (such as communication and power conduits under hardstand areas, and space in control rooms).

- If a flood wall is not desirable or if construction access for building a flood wall is not going to be practical in the future once the site is developed, it may be better to lift the site levels or build the flood wall as part of the current works.

Uncertainty has always been part of engineering design, as has making decisions with imperfect knowledge. Climate systems in particular are subject to a wide range of natural variability over a wide range of times scales. What’s different now is that the future is more obviously uncertain and changing more rapidly. For example, where once we could use rainfall tables in textbooks for decades, now it seems that every few years there are new projections from the IPCC about large or small changes in our understanding. It’s a dynamic time for making decisions. But this isn’t all bad news.

Looking forward

If you’re planning an improvement project and the future is expected to bring larger floods, your return on investment may be quicker than expected. With the expected increases to rare rainfall intensities and the increasing uncertainty, there should be more confidence in investing in solutions to improve the performance of surface water infrastructure. In the same way, you’ll get a faster return on your investment in improving your engineering skills related to climate, hydrology and hydraulics of surface water systems and associated infrastructure design.

While considering the worst, we hope for the best. The fossil-fuel development emission scenario (SSP5) is based on us continuing the polluting hydrocarbon-based developments of the past. Entura is actively supporting our clients to pursue low emissions developments and more renewable energy for a better future. A best-case scenario is shown in the diagram below as SSP1 (called the sustainability scenario). In this scenario, with 2.6 W/m² radiative forcing, the projection for 2090 would be an increase of 1.7 °C in global temperature over the 1961–90 climate, and only a 14–27 % increase in intense rainfall (for 24 hour and longer to 1 hour and shorter durations respectively).

To prevent the extreme global temperatures projected to arise from polluting the atmosphere, it’s up to all of us to keep changing for a better future.

Figure of projected temperature increases associated with AR6 shared socioeconomic pathways relative to 1961–90 (shaded in grey) and their associated uncertainty (Engineers Australia, 2023)

References

Engineers Australia (2023) Update to the Climate Change Considerations chapter in Australia Rainfall and Runoff, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water https://storage.googleapis.com/files-au-climate/climate-au/p/prj2aec7b7ec59ab390bffc6/public_assets/Draft%20update%20to%20the%20Climate%20Change%20Considerations%20chapter.pdf.

Meinshausen et al. (2020). The shared socio-economic pathway (SSP) greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions to 2500. Geoscientific Model Development, 13(8), 3571–3605. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-3571-2020.

Visser, Kim, Wasko, Nathan and Sharma (2022), The Impact of Climate Change on Operational Probable Maximum Precipitation Estimates, Water Resources Research, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR032247.

Wasko, Westra, Nathan, Pepler, Raupach, Dowdy, Johnson, Ho, McInnes, Jakob, Evans, Villarini and Fowler (2024), A systematic review of climate change science relevant to Australian design flood estimation, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-28-1251-2024.

If you’d like to talk with Entura about your water project, contact Phillip Ellerton.

About the author

Dr Colin Terry is a civil engineer at Entura with three decades of experience in Australia and New Zealand. His experience includes modelling, planning, design and construction support. He has worked on multidisciplinary projects across various parts of the water cycle including catchment management, water supply, hydropower, land development, transport, and water quality in natural systems – with a focus on surface and piped water.

MORE THOUGHT LEADERSHIP ARTICLES

Ten tips for developing your engineering career

From Baby Boomers to Gen Alpha, the generation names and characteristics come and go – but despite the changing working styles and preferences of older and younger engineers, some things stay the same. Developing good engineers still calls for many elements that have shaped countless careers over time: people who were willing to share their knowledge and experience, opportunities to develop and refine the engineering craft, and mentors to support us, believe in us and help us make the next step.

I’ve been reflecting on these dynamics at this senior point in my 34-year career – and I’d like to share some tips to help set younger engineers on a path towards achieving a satisfying, successful career.

Tip #1 – Never stop learning

Graduating with a formal engineering qualification is only the first milestone in your learning. Explore whether there are postgraduate courses that can help you grow and open up opportunities that interest you. It isn’t easy to balance postgrad studies with work – let alone with the family responsibilities that many people experience in their early/mid adulthood. You’ll need to think carefully about how much time you can devote – and how to maintain a healthy work/study/life balance.

Also look at what your workplace can offer in terms of internal programs, such as broad-based leadership programs. An industry body will often offer short courses and will also provide networking opportunities where you can learn from other people – so join a professional association. Beyond formal courses, you can use your development plan to your advantage by identifying areas that interest you and seeking variety in the kinds of tasks and projects you are assigned.

Whatever career stage you’ve reached, stay interested, interact, and keep asking questions. It’s a great antidote to becoming a ‘know it all’ or getting stuck in a rut! At the end of each year, ask yourself, ‘What have I learnt that’s new?’ If you can’t think of anything, then maybe you’re playing it too safe and it’s time to change things up a bit.

Tip #2 – Seek mentors

Mentors – whether formal or informal – can give you technical insights and can also help guide your broader professional journey. Use mentors to extend your learning beyond your allocated tasks, such as how to be a good consultant, or just broaden your understanding. Think broadly about who you could seek out as mentors along your career journey. For example, some of the members of independent review panels have become de facto mentors to me. Value your mentors, and try to give something back or pay it forward to the next young engineer.

Tip #3 – Pursue breadth as well as depth

Breadth is as important as depth. Try to achieve more breadth before you specialise, because breadth will make you a better expert (where you have depth) and extend your value as a consultant. For me, experience in designing and constructing dams and hydropower as well as stints in hydrology and modelling gave me a more holistic understanding of dam projects. Try to get some experience in other related disciplines, so you are better placed to manage multi-disciplined projects; and get some construction experience so you can see how your designs translate on the ground.

The value of broad experience is evident in the 16 competencies set out by Engineers Australia for ‘Chartered Engineer’ status. Use them to work towards becoming chartered – a target that every engineer should strive for.

Tip #4 – Seize opportunities

Only you can act to take the opportunities that emerge in your career, to make the most of them, and to learn from them. If you think too long, the opportunity may disappear or someone else may seize it. This will sometimes require sacrifices – such as periods away from home, which can be hard – but sometimes a little adversity can really spur your professional and personal development. Opportunities could be a particular project, an opportunity to work with someone you want to learn from, or an interesting career episode in a different place or a different role.

Tip #5 – Take some risks

If someone you respect believes you can do a role on a project, maybe you should too. Stretching yourself will help you develop. Jumping – or being thrown– into the deep end can be a great way to learn, as long as you’re supported so you don’t sink. Talk to your mentors and managers about how they can support you to thrive rather than flail. Remember that mistakes and failures are not the end – they are excellent stimulus for learning, and you certainly won’t be the first to experience them.

Tip #6 – Be strategic

Your employer’s responsibility is to create an environment in which you are able to develop, but ultimately your career is your responsibility. What do you need to learn or achieve in order to get where you want to end up? How can you position yourself so that you’re ready when opportunities emerge? For me, this was the need to have a Masters degree to take on team leader roles on bank-funded international projects – which spurred me to return to study. You could use the competencies for Engineering Chartered status as a benchmark to identify gaps and then work to fill them.

Tip #7 – See things through from start to finish

Look for opportunities to be involved in a project from inception through to commissioning. You will learn a great deal from seeing how the investigations and decisions taken in the design play out in the actual conditions on site as well as the constructability and the performance of the structure. These experiences will shape your expertise, how you operate in the future as an engineer, and the advice you give your future clients. This is equally relevant for other programs of work, seeing the program from a conceptual stage to an operational stage.

Tip #8 – Build your consulting skills

If you want to work in consulting, you need to become more than a technical expert. An ideal consultant needs technical expertise, but also needs to be able to engage effectively with clients, to communicate well (both in writing and orally), to be creative and solve problems, and to manage and deliver projects. These skills are valuable for everyone, regardless of your role. Taking up different roles through your career can also help you see things from different perspectives and become a better consultant. Every experience helps to build the consultant you become.

Tip #9 – Listen to feedback

Even if it’s uncomfortable to receive, seek out feedback and use it constructively to learn more about yourself, your skills and how you interact with others. Everyone has facets in their knowledge, performance and personality that can be enhanced. The more you can see yourself through the eyes of your colleagues, the better you’ll be able to play to your strengths and work on your weaknesses. In the end, many engineering projects require a team to deliver, so if you know your strengths and weaknesses, you can create a balanced team that capitalises on the synergies.

Tip #10 – Remember the circle of life

What goes around comes around. In the early stages of your career, it’s natural to expect support and development. Eventually, as you progress, your expectation should shift to helping develop others. I believe that this cycle should be faster than most people would expect. You don’t need to wait decades. Once you have been doing something for a few years, you can help others, and by doing so you will reinforce your learnings and improve your ability to explain complex technical elements. Developing others will also develop you.

I hope that other Baby Boomers and Generation Xs are inspired by these tips to reflect on your own experiences, share your recipes for success, and look out for where you can help others grow. It’s in all of our interests for the engineering profession to thrive.

Head to our careers page for current opportunities at Entura.

About the author

Richard Herweynen is Entura’s Technical Director, Water. He has more than three decades of experience in dam and hydropower engineering, and has worked throughout the Indo-Pacific region on both dam and hydropower projects, covering all aspects including investigations, feasibility studies, detailed design, construction liaison, operation and maintenance and risk assessment for both new and existing projects. Richard has been part of a number of recent expert review panels for major water projects. He participated in the ANCOLD working group for concrete gravity dams and was the Chairman of the ICOLD technical committee on engineering activities in the planning process for water resources projects. Richard has won many engineering excellence and innovation awards (including Engineers Australia’s Professional Engineer of the Year 2012 – Tasmanian Division), and has published more than 30 technical papers on dam engineering.

MORE THOUGHT LEADERSHIP ARTICLES

Breathing new life into Australia’s aging wind farms

The wind industry, well-established in Europe for decades, took baby steps onto Australian soil in the late 1980s and 1990s. By the early 2000s, Australia’s new wind industry was ready to take off. Given that wind farms usually have a design life of anywhere between 15 and 30 years, our earliest wind farms are now reaching retirement age. The industry therefore faces a new set of challenges. Can these older wind farms continue to serve their important role in Australia’s clean energy transition or are they at their end of life?

So far, few wind farms in Australia have been decommissioned, dismantled and removed from the land. With many of our older wind farms sited to capture the best wind resources, there’s every reason to try to continue using these sites to harness wind energy.

One option is to squeeze more years out of the wind farm through effective maintenance and supportive analysis to ensure it is safe to do so while accepting that there may be increasingly frequent outages and increased maintenance costs to keep the wind turbines in service. However, although operation beyond the nominal life of a wind turbine is theoretically feasible, old wind turbines can’t keep spinning forever and will need to be stopped at some stage.

Other options for aging wind farms are refurbishment of some parts of the turbines, or full ‘repowering’ with completely new machines. This could also include a full redesign to accommodate larger turbines or to incorporate solar or battery energy storage systems.

An example of rejuvenation

Small grids may be some of the first to need to consider what to do about old wind farms. As an example, Hydro Tasmania’s Huxley Hill Wind Farm on King Island has three 250 kW wind turbines that were installed in 1998, and two 850 kW wind turbines that were installed in 2003.